Pages

▼

Thursday, December 19, 2019

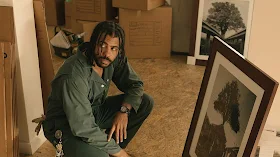

Blindspotting (Carlos López Estrada, 2018)

Blindspotting (Carlos López Estrada, 2018)

Cast: Daveed Diggs, Rafael Casal, Janina Gavankar, Jasmine Cephas Jones, Ethan Embry, Tisha Campbell-Martin, Utkarsh Ambudkar, Kevin Carroll, Nyambi Nyambi, Jon Chaffin, Wayne Knight, Margo Hall. Screenplay: Rafael Casal, Daveed Diggs. Cinematography: Robbie Baumgartner. Production design: Tom Hammock. Film editing: Gabriel Fleming. Music: Michael Yezerski.

Blindspotting sets up its essential high-wire tension early in the film when we see Collin (Daveed Diggs) being given the terms of his probation after being released from prison: the usual no drugs, no firearms, no bad company, and so on. Whereupon we almost immediately see him sitting in the back seat of a two-door car that all of a sudden is bristling with the owner's guns. Collin panics: He has three days left before his probation ends. Things get worse when Collin's best friend, Miles (Rafael Casal), reveals that he's carrying too. Collin panics, and when he's released from the car heads for the truck he's driving -- he has taken a job with a moving company managed by his ex-girlfriend, Val (Janina Gavankar) -- eager to get to his halfway house before his 11 p.m. curfew. And then he's stopped by a red traffic light that shows no sign of changing, even though there's absolutely no other traffic moving. As he fumes in frustration, a man suddenly runs up to the truck, followed quickly by a cop on foot. As Collin looks on in horror, the cop fires four bullets, killing the other man -- we see him fall in Collin's rear-view mirror. Like Collin, the man is black. And through his side window Collin looks face to face at the cop, who is, needless to say, white. But then the light changes and Collin drives home. Blindspotting is like that throughout, though the rest of Collin's hair's-breadth moments don't involve a fatality. It's about the precariousness of being black when even your closest white friends, like Miles, don't understand the ease with which things can go suddenly wrong. We're constantly aware of the way the world -- or at least Oakland, the beautifully characterized milieu in which Collin's story takes place -- can suddenly turn against Collin, who just wants to stay out of jail. But the remarkable thing about this real and painful fact is that it's the premise on which a very funny and very insightful movie is based. There are critics who fault Blindspotting for an inconsistency of tone, for having one foot in farce and the other in tragedy, but I think that's the brilliance of the film. I doesn't need to hammer its message home. It can make a point about, say, gentrification by showing Collin and Miles at work cleaning out the "junk" in a house that's about to be gutted and turned into an upscale townhouse, just by taking a look at what's been left behind by its former residents: a wedding photograph, an old photo album, in short, a cache of memories about to be obliterated. And it culminates in a lovely sequence in which Collin comes face to face again with the cop, and conquers the man not with a gun but with a rap diatribe. There are those who think this is only a disguised version of the conventional happy ending, but I prefer to see it as a hopeful resolution of the cultural dissonance in which we now live.

Charles Matthews