A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Claude Chabrol. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Claude Chabrol. Show all posts

Tuesday, December 29, 2015

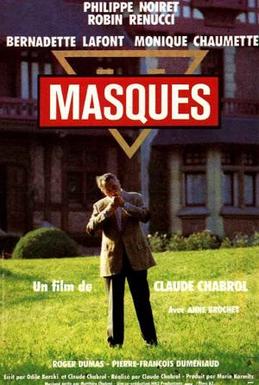

Masques (Claude Chabrol, 1987)

Masques shares the style (and the one-word title) of those 1960s romantic thrillers like Charade (Stanley Donen, 1963), Arabesque (Stanley Donen, 1966), and Kaleidoscope (Jack Smight, 1966) that inevitably got called "Hitchcockian." So it's not surprising that Chabrol, who recognized Hitchcock's genius when Hollywood still thought of him as just a popular entertainer, should cast an hommage to the director in their manner. Roland Wolf (Robin Renucci) is writing a biography of Christian Legagneur (Philippe Noiret), who hosts a cheesy TV talent/game show featuring senior citizens, so he comes to spend a week at Legagneur's estate near Paris. There he's introduced to a houseful of eccentrics: Legagneur's mute chauffeur/cook, Max (Pierre-François Dumeniaud); his secretary, Colette (Monique Chaumette); and a couple, Manu (Roger Dumas), a wine connoisseur who is helping stock Legagneur's cellar, and his wife (or perhaps mistress), who is a masseuse and reads tarot cards (Bernadette Lafont). (Lafont gets third billing after Noiret and Renucci, though hers is decided a secondary role, perhaps because she appeared in Chabrol's first film, Le Beau Serge, in 1958, and worked with him again several times during their long careers.) But most intriguing of all to Wolf is Legagneur's pretty young goddaughter, Catherine (Anne Brochet), who Wolf is told is recovering from a serious illness and is quite fragile. It's clear to the audience from Catherine's erratic behavior that she's drugged -- whether as part of her therapy or not is the question raised in Wolf's mind. For no one in this household is exactly what they seem, least of all Wolf, who, when he's alone in his room, removes a gun from his shaving kit and hides it on a shelf. On the shelf he finds a lipstick and with it, murmuring "Madeleine," he writes a large "M" on a mirror, then rubs it out. Madeleine, we will learn, is Wolf's sister, who is said to have quarreled with Catherine and then left on a trip to the Seychelles, which Wolf seriously doubts. Madeleine is also, of course, the name of the character played by Kim Novak in Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958), one of several "Easter eggs" for Hitchcockians left by Chabrol in the film. Legagneur's TV show, for another example, uses as theme music Gounod's "Funeral March for a Marionette," which was the theme music for Hitchcock's own TV show. Masques failed to find an American distributor when it was first released, but is now available on video. It's definitely minor Chabrol, but Noiret is terrific as the affably sinister Legagneur.

Monday, December 28, 2015

La Cérémonie (Claude Chabrol, 1995)

|

| Valentin Merlet, Jacqueline Bisset, Virginie Ledoyen, and Jean-Pierre Cassel in La Cérémonie |

Sophie: Sandrine Bonnaire

Georges Lelièvre: Jean-Pierre Cassel

Catherine Lelièvre: Jacqueline Bisset

Melinda: Virginie Ledoyen

Gilles: Valentine Merlet

Jérémie: Julien Rochefort

Mme. Lantier: Dominique Frot

Priest: Jean-François Perrier

Director: Claude Chabrol

Screenplay: Claude Chabrol, Caroline Eliacheff

Based on a novel by Ruth Rendell

Cinematography: Bernard Zitzerman

Production design: Daniel Mercier

Film editing: Monique Fardoulis

Music: Matthieu Chabrol

Claude Chabrol's La Cérémonie begins with a long tracking shot through the window of a café, picking up Sophie as she walks toward her appointment with Catherine Lelièvre. Catherine is as chic as Sophie, boyishly dressed with her hair cut in too-short bangs, is drab. The Lelièvres need a housekeeper, Catherine tells her, and Sophie presents the letter of reference from her most recent employer. The interview is slightly awkward, partly because Sophie is oddly oblique in her answers. But Catherine has a large house in a remote location and she needs a housekeeper right away. When Catherine drives Sophie to the house, a young woman named Jeanne appears and hitches a ride to the village near the Lelièvres house; Jeanne, who is as brashly forward as Sophie is reserved, works in the village post office. At the house, Sophie meets Catherine's husband, Georges, a rather blustery businessman, and her son from a previous marriage, the teenage Gilles, and stepdaughter, a university student named Melinda. Sophie proves to be an excellent cook and a reliable maid-of-all-work, but we soon discover that she has a secret or two. One is that she's illiterate, the result of a profound dyslexia. She doesn't drive, being unable to pass a driving test, and pretends that she needs glasses. When Georges insists on taking her to an optometrist, she ducks out of the appointment and buys a cheap pair of drugstore glasses -- though even then she is unable to give the sales clerk the exact change. Waiting for Georges, she meets Jeanne again, and the two women strike up a friendship. Jeanne, it turns out, knows another secret of Sophie's, which is that she was accused of setting fire to her house, killing her disabled father. Jeanne herself was accused of abusing her daughter, born out of wedlock, and causing her death, but both women were acquitted for lack of evidence. And so the stage is set for a story of folie à deux that Chabrol and Caroline Eliacheff adapted from a novel, A Judgment in Stone, by Ruth Rendell. Bonnaire and Huppert are extraordinary in their contrasting styles: Bonnaire passive, almost autistic in manner, Huppert bold and outgoing. The climax, in which a frenzied Jeanne releases Sophie's pent-up hostility, is shattering.

Story of Women (Claude Chabrol, 1988)

"Women's business," according to the subtitle, is what Marie Latour (Isabelle Huppert) tells her husband (François Cluzet) is going on behind closed doors in their apartment. The business is abortion, which Marie provides for prostitutes and other women who are finding childbirth to be a burden during the German occupation of France. But "Women's Business" might also be an apt translation of the original title of Chabrol's film, Une Affaire de Femmes. Based on the true story of Marie-Louise Giraud, who went to the guillotine in 1943 for the abortions she had induced, Story of Women is a deeply feminist film, though never a preachy one. Huppert, as usual, gives an extraordinary performance, emphasizing not only her character's determination to do what she thinks is right for the women she knows, but also her profoundly fatal naïveté about the politics of the era in which she is living. "Women's business" is to survive the ignorance and brutality of men, by any means necessary, but it betrays Marie into some choices that a woman with more knowledge of the way the world works might avoid. She loses sight of the fact that she became an abortionist to survive the deprivation that threatens her life and that of her children, and becomes fixated on their greatly improved standard of living and the possibility that she might earn enough to fulfill her dream of becoming a professional singer. (A distant dream, as her performance of a song in an audition for a music teacher suggests.) In the end, she goes to a guillotine that is not the toweringly glamorous instrument of death we've grown accustomed to from films about the French Revolution, but a grim and shabby little affair cobbled together from plywood and sheet metal -- a fitting image for the shabbiness of the Vichy régime and its treatment of those it saw as a threat.

Sunday, December 27, 2015

Le Beau Serge (Claude Chabrol, 1958)

Le Beau Serge has been called the first film of the French New Wave because it was made before the first features by Claude Chabrol's fellow Cahiers du Cinéma critics, François Truffaut's The 400 Blows (1959) and Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (1960). The two later films were bigger successes internationally, but the influence of Chabrol's debut on the look, the narrative, and the technique of film continued to be felt, and his next movie, Les Cousins (1959), established Chabrol's reputation. Like Truffaut and Godard, who made international stars of Jean-Pierre Léaud and Jean-Paul Belmondo with their features, Chabrol launched the careers of Gérard Blain and Jean-Claude Brialy, who appeared in his first two films. In Le Beau Serge, Blain plays the title role, a young man who, by staying in his provincial village (Chabrol's own home town of Sardent), becomes an alcoholic layabout, trapped in an unhappy marriage. Brialy plays François, an old friend of Serge's, who left Sardent and became a success, but now returns home after a long absence to recuperate from a lung ailment. The roles are striking in both the similarity to and the differences from the ones Blain and Brialy play in Les Cousins, which takes place in Paris, where Blain is the strait-laced provincial and Brialy is his dissipated cousin. Le Beau Serge follows François's somewhat misguided attempt to help Serge clean up his life, which is complicated when François begins an affair with Serge's sister-in-law, Marie (Bernadette Lafont). In the climax of the film, Serge's wife, Yvonne (Michèle Méritz), goes into labor with the child everyone in the village expects to be deformed or stillborn, as their first child was. In a howling snowstorm, François takes it on himself to go in search of the village's doctor, and then looks for Serge, who is sleeping off a drunk in a chicken coop. The concluding scene, of Serge convulsed in hysterical laughter, is profoundly ambiguous. Chabrol's use of the actual village of Sardent, including many of its townspeople as actors, is brilliantly done, greatly aided by Henri Decaë's cinematography. Les Cousins is a more sophisticated and satisfying film, but it really has to be seen in tandem with Le Beau Serge. Both actors are terrific, but Blain attracted more attention because of his supposed resemblance in both looks and style to James Dean, though to my mind he recalls Montgomery Clift more than Dean.

Saturday, December 26, 2015

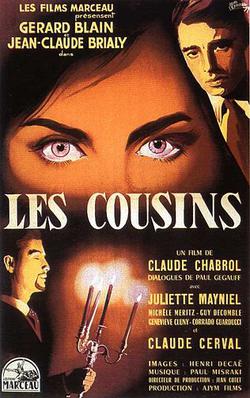

Les Cousins (Claude Chabrol, 1959)

Chekhov's gun plays a major role in Les Cousins, heightening the suspense about who will use it on whom. But the film isn't a suspense thriller, despite Chabrol's admiration for Hitchcock, so much as it is a deliciously perverse adaption of some classic fables: the country mouse and the city mouse, and the ant and the grasshopper. It also resonates ironically with Balzac's Lost Illusions, the novel that a bookseller (Guy Decomble) allows Charles (Gérard Blain) to "steal" from his shop. In the Balzac novel, a young man from the provinces goes to Paris to seek fame, fortune, and love, and his misadventures wreak havoc on himself and the people he loves. In Les Cousins, country mouse/ant Charles goes to Paris to share an apartment with his cousin, Paul (Jean-Claude Brialy), the city mouse/grasshopper, while both study law. Paul is a somewhat decadent hedonist, who tries to introduce the straiter-laced Charles, who is very much dedicated to his mother back home, to the delights of the city. One of these delights is the promiscuous Florence (Juliette Mayniel), with whom Charles falls in love, only to have things end badly when she chooses to live with Paul instead. Chabrol fills the movie with quirky, somewhat sinister characters, though never turns the film into a clear-cut tale of good vs. evil. Innocence doesn't triumph over cynicism here, though cynicism pays a price, which is what makes Chabrol's film such a grandly satisfying one to watch and to think about afterward. Blain and Brialy (in a suitably Mephistophelean mustache and beard) are brilliant, and the cinematographer, Henri Decaë, gives us a grand evocation of Paris in the 1950s.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)