|

| James Mason, Dan Duryea, and William Conrad in One Way Street |

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label James Mason. Show all posts

Showing posts with label James Mason. Show all posts

Tuesday, April 30, 2024

One Way Street (Hugo Fregonese, 1950)

Sunday, February 2, 2020

The Wicked Lady (Leslie Arliss, 1945)

|

| Margaret Lockwood in The Wicked Lady |

Entertaining claptrap about a Restoration beauty (Margaret Lockwood) named Barbara who seduces the wealthy squire Sir Ralph Skelton (Griffith Jones) on the eve of his marriage to the virtuous Caroline (Patricia Roc). But having married Sir Ralph, Barbara quickly becomes bored with life in the country, dresses in men's clothes, sneaks out by a secret passage, and turns highwayman. This puts her in competition with (and the bed of) the notorious Capt. Jerry Jackson (James Mason), the terror of the county's roads. Eventually the wicked are punished and virtue is rewarded, of course. The story needs a little more tongue in cheek than writer-director Leslie Arliss is able to give it, but it moves along nicely. Mason, as usual, gives the standout performance.

Saturday, September 29, 2018

Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (Albert Lewin, 1951)

|

| Ava Gardner and James Mason in Pandora and the Flying Dutchman |

Pandora Reynolds: Ava Gardner

Stephen Cameron: Nigel Patrick

Janet: Sheila Sim

Geoffrey Fielding: Harold Warrender

Juan Montalvo: Mario Cabré

Reggie Demarest: Marius Goring

Angus: John Laurie

Jenny: Pamela Mason

Peggy: Patricia Raine

Señora Montalvo: Margarita D'Alvarez

Director: Albert Lewin

Screenplay: Albert Lewin

Cinematography: Jack Cardiff

Production design: John Bryan

Film editing: Ralph Kemplen

Costume design: Beatrice Dawson

Music: Alan Rawsthorne

James Mason was a handsome man and a very fine actor but he seems a little miscast as the doomed and dashing Flying Dutchman, especially opposite the earthy Ava Gardner as the embodiment of the Dutchman's lost love. It's a role that calls less for Mason's cerebral, inward qualities than for a swashbuckling ladykiller of the Errol Flynn mode. That said, Mason's presence in the film is one of the things that have kept Albert Lewin's romantic fantasy Pandora and the Flying Dutchman on view for so long, even giving it minor cult status. There's a gravitas to his Dutchman that makes it possible for him to quote Victorian poetry -- Matthew Arnold's "Dover Beach" and Edward Fitzgerald's translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam -- without looking foolish. There's also Jack Cardiff's Technicolor cinematography and John Bryan's handsome sets to the film's credit. Lewin's screenplay, unfortunately, tends to the portentous and the pretentious, including maxims like "To understand one human soul is like trying to empty the sea with a cup" and "The measure of love is what one is willing to give up for it," not to mention purple passages like the Dutchman's "My mind was a hive of swarming gadflies, whose stings were my remorseless thoughts." But above all there's Gardner's scorching beauty, which transcends the absurdities of the role -- and her rather limited acting resources -- to make it credible that Reggie should take poison, Geoffrey should send his racing car over a cliff, and Juan should die in the bullring, all for her sake.

Sunday, July 16, 2017

Bigger Than Life (Nicholas Ray, 1956)

|

| James Mason and Christopher Olsen in Bigger Than Life |

Lou Avery: Barbara Rush

Richie Avery: Christopher Olsen

Wally Gibbs: Walter Matthau

Dr. Norton: Robert F. Simon

Dr. Ruric: Roland Winters

Bob LaPorte: Rusty Lane

Director: Nicholas Ray

Screenplay: Cyril Hume, Richard Maibaum

Based on a magazine article by Berton Roueche

Cinematography: Joseph MacDonald

Music: David Raksin

Making a domestic drama like Bigger Than Life in CinemaScope is a bit like sending a love letter in a business envelope: The carrier feels wrong for the message. And yet, Nicholas Ray makes it work, partly by acknowledging the irony and playing with it. CinemaScope's outlandish dimensions were designed to put up a fight against the tiny TV screens of the day, which were rapidly becoming the venue for domestic dramas and situation comedies focusing on everyday family life. So Ray makes Bigger Than Life into a kind of companion piece for his Rebel Without a Cause (1955): Both films are antithetical to the portraits of 1950s families on shows like Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver.* Ray also uses CinemaScope for shock value. The wide screen was designed to provide almost more information than the viewer could process. It's hard to hide things from a viewer if the screen is testing the limits of peripheral vision, but Ray and cinematographer Joseph MacDonald manage it beautifully in the scene in which young Richie Avery frantically hunts through his father's things for the medicine that is causing his father's psychotic behavior. Finally he locates the pills, hidden behind the drawer underneath a mirror on top of a dresser, but as he shoves the drawer back in, the mirror changes angles to reveal his father's face behind him. Although the scene would have worked in a standard format, the wide screen heightens the surprise by almost lulling us into thinking that we could see everything in the room. Bigger Than Life was a flop in its day, despite its ripped-from-the-headlines premise -- Miracle Drug May Be Driving You Crazy -- and one of James Mason's best performances. It may have failed because audiences weren't ready for a portrait of the dark side of American family life that wasn't based, like Rebel Without a Cause, on "juvenile delinquency" or, like Peyton Place (Mark Robson, 1957), on sex. Bigger Than Life suggested that we shouldn't trust those we were most inclined to trust: doctors and pharmacology. The physicians in the film are cold, gray men with no bedside manner, stonewalling questions from the patient's wife and imperiously clinging to their expertise. The film also gives us a rather chilling portrayal of conventional attitudes toward mental illness, a stigma far worse than any physical disorder. Ed's wife, Lou, resists the idea that her husband might be psychotic simply because it might endanger his job. Barbara Rush gives a capable performance, most effectively when she snaps under the constant pressure and smashes a bathroom mirror, but the role really needed an actress of more consistent depth and range, someone like Jean Simmons for example, so that Lou doesn't just stand around prettily fretting so much. There are also some nice touches in the otherwise conventional pretty suburban decor of the Averys' house, such as the corroded old water heater in the kitchen, a persistent symbol of the precariousness of the family finances, and the rather dark travel posters of Rome and Bologna that hint at a desire to escape. The "hopeful" ending is also nicely ambiguous.

*The Beaver himself, Jerry Mathers, has a blink-and-you'll-miss-it walk-on bit as one of the schoolkids in Bigger Than Life.

Watched on Turner Classic Movies

Tuesday, May 23, 2017

Odd Man Out (Carol Reed, 1947)

|

| James Mason and Kathleen Ryan in Odd Man Out |

Kathleen Sullivan: Kathleen Ryan

Lukey: Robert Newton

Pat: Cyril Cusack

Shell: F.J. McCormick

Fencie: William Hartnell

Rosie: Fay Compton

Inspector: Denis O'Dea

Father Tom: W.G. Fay

Theresa O'Brien: Maureen Delaney

Dennis: Robert Beatty

Nolan: Dan O'Herlihy

Director: Carol Reed

Screenplay: F.L. Green, R.C. Sheriff

Based on a novel by F.L. Green

Cinematography: Robert Krasker

Art direction: Ralph W. Brinton

Film editing: Fergus McDonell

Music: William Alwyn

The collaboration of director Carol Reed and cinematographer Robert Krasker on Odd Man Out is perhaps not as celebrated as the one on The Third Man (1949), but in some ways it's more impressive. The Third Man has a tighter screenplay and a location, postwar Vienna, that lent itself more readily to the kind of expressionistic atmosphere Krasker's images of it supply. Odd Man Out is a looser, more episodic story. As its title almost suggests, it's a kind of reworking of the Odyssey, the archetypal perilous-journey narrative. Reed made a decision at some point to treat the first part of the film, the planning and commission of the heist, in a conventionally realistic fashion and then gradually to shift into something more expressionistic, something that reveals the disintegrating state of the dying Johnny McQueen's mind. He needed an actor like James Mason, who could give Johnny the necessary charisma while still suggesting from the outset the character's damaged state of mind. But he also needed Krasker's ability to present actuality and then to transform it into something stranger than reality, to suggest the menace lurking in the mundane streets of Belfast and then to work with the baroquely sinister sets designed by Ralph W. Brinton that include the ornate Four Winds Saloon (based on an actual Belfast pub but created in the studio) and the decaying Victorian residence of Shell and the mad painter Lukey. We first begin to see the transition when Johnny experiences vertigo while riding through the streets of the city, but from the moment when the wounded Johnny takes cover in an abandoned air-raid shelter, where reality becomes indistinguishable from Johnny's fevered prison memories and other hallucinations, the film increasingly steps away from realism. Even the weather plays a role in subverting realism: The semi-conscious Johnny is left by Shell in an old bathtub in a lot filled with junk, including a statue of an angel whose nose seems to run after the rain starts to fall. Later, when rain has turned to snow, an icicle hangs from the drippy nose. The encounters with Belfast street kids are like meeting the children of Pandemonium. The cast, much of it recruited from Dublin's Abbey Theatre, is superb, including Kathleen Ryan, Cyril Cusack, Dan O'Herlihy, and Denis O'Dea. Robert Newton received pre-title second billing with Mason, which is certainly out of keeping with the size of his role, and there are those who find Newton's Lukey out of key with the less showy performances of the other actors: Pauline Kael calls it "a badly misconceived performance in a badly misconceived role." But for me it brings the ferment of the manhunt and the increasingly bizarre handing-about of Johnny to a kind of necessary climax before Johnny's reunion with Kathleen and the inevitable outcome.

Wednesday, April 26, 2017

The Last of Sheila (Herbert Ross, 1973)

Actor Anthony Perkins and songwriter Stephen Sondheim moonlighted as screenwriters to create this jeu d'esprit, a murder mystery involving the kind of elaborate games that Perkins and Sondheim and their friends used to play: treasure hunts with ingenious clues. The setup is this: A year earlier, Sheila, the wife of film producer Clifton Green (James Coburn), was killed in a hit-and-run accident. Green invites six people who were at a party the night of her death to spend a week on his yacht, which is named for her. Before they board, he arranges them for a photo under her name on the prow of the yacht. Then he announces that he is going to give each of them an envelope that contains a secret: something that a person would want to conceal about themselves. Each night, they will dock at a different location and will be given a clue that they must follow to discover the secret. If the person who holds the card with the secret on it solves the puzzle, the hunt of the night is over. So, on the first night, the clues lead to the secret: "Shoplifter." And when Philip (James Mason), a washed-up film director who holds that clue, solves it, the game ends. But the next night, the game isn't completed: Green is found murdered during the hunt. Meanwhile, realization dawns in the group that the secrets were their own: Philip wasn't a shoplifter, but the actress named Alice (Raquel Welch) admits that she once lifted a valuable fur coat from a store. And when the secret for the night Green is killed is revealed to be "Homosexual," Tom (Richard Benjamin), a screenwriter, admits that he and Green once had a brief affair. And so it appears that Green was murdered by someone who didn't want their secret to come out. But just when it appears that the murder has been solved, there's another intricate twist. The screenplay is fiendishly clever, and it's well acted: The other players include Dyan Cannon as a high-powered agent, Joan Hackett as Tom's rich heiress wife, and Ian McShane as Alice's manager-husband. Unfortunately, Herbert Ross directs things a little clunkily, although some of the awkwardness may come from the fact that shooting began on the yacht itself, but bad weather held up the shoot and sets eventually had to be constructed on a soundstage. There was also reportedly some conflict among the cast members and the director, centering on Welch. Today, some of the film's attitudes seem a little antique: Homosexuality is no longer such a terrible secret, although at the time Perkins and Sondheim, both of whom were gay, were still closeted. And perhaps not enough is made of the fact that one of the clues outs a character as a former child molester. The resulting film is something like a soufflé that didn't rise, turning out tasty but a little chewy. The best moments belong to, not surprisingly, Cannon, one of those performers who make every film they're in a little better.

Friday, July 15, 2016

Julius Caesar (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1953)

Julius Caesar is the starchiest of Shakespeare's major plays, the one with the least sex, which is why many of us first encounter it in a high school English class. It's a play about soldiers and politicians, professions from which women were (unless they were Queen Elizabeth) excluded in Shakespeare's time, so there are only two female roles: Brutus's wife, Portia, and Caesar's wife, Calpurnia, and both of them are almost walk-ons. (My high school drama teacher wanted to stage Julius Caesar as our class play until he realized that three times as many girls as boys wanted to try out for parts.) So the remarkable thing about MGM's all-star production is that it turned out so well: It's one of the best Hollywood productions of Shakespeare. (Calpurnia and Portia are lavishly cast with Greer Garson and Deborah Kerr, respectively, in the small roles.) That said, it's a shame that not quite enough was done to take the starch out of the play. The casting of Marlon Brando as Mark Antony was a start, but although it's a very good performance, it tends to throw the film out of whack. When it was released, Brando had been stereotyped as a "Method mumbler," for his celebrated performance on stage and screen as Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire (Elia Kazan, 1951). Could he rise to the demands of speaking Shakespearean diction? critics burbled. Of course he could, with a little bit of coaching from his distinguished co-star John Gielgud, who plays Cassius, and who was so impressed that he wanted Brando to go to London where he would direct him in Hamlet. That, of course, never took place, more's the pity. But the attention directed at Brando does tend to shift the focus away from the real central character of the play, Brutus, played with exceptional distinction by James Mason. Gielgud is also very good, although it seems to me that in the first part of the film he is a bit too stagy. Mason gives a kind of colloquial spin to his lines -- a sense that he's speaking what Brutus thinks and feels, and not reciting Shakespearean verse. Later in the film, when Brutus and Cassius go to war against Antony, Gielgud has loosened up more. Mankiewicz's adaptation of the play is solid, and he does smart things with camera placement -- putting the camera in the middle of the crowd, for example, when Brutus and Antony give their great speeches after Caesar's (Louis Calhern) assassination. But there is a kind of Hollywood Rome quality to the film -- not surprising, since it was made after the lavish MGM spectacle Quo Vadis (Mervyn LeRoy, 1951) and uses some of the same sets -- that tends toward the stodgy. That's more surprising when you realize that the producer of the film was John Houseman, who had also been a producer of Orson Welles's celebrated 1937 modern-dress Mercury Theatre production of the play, which created a sensation with its evocation of the rise of fascism in Italy and Germany.

Friday, February 19, 2016

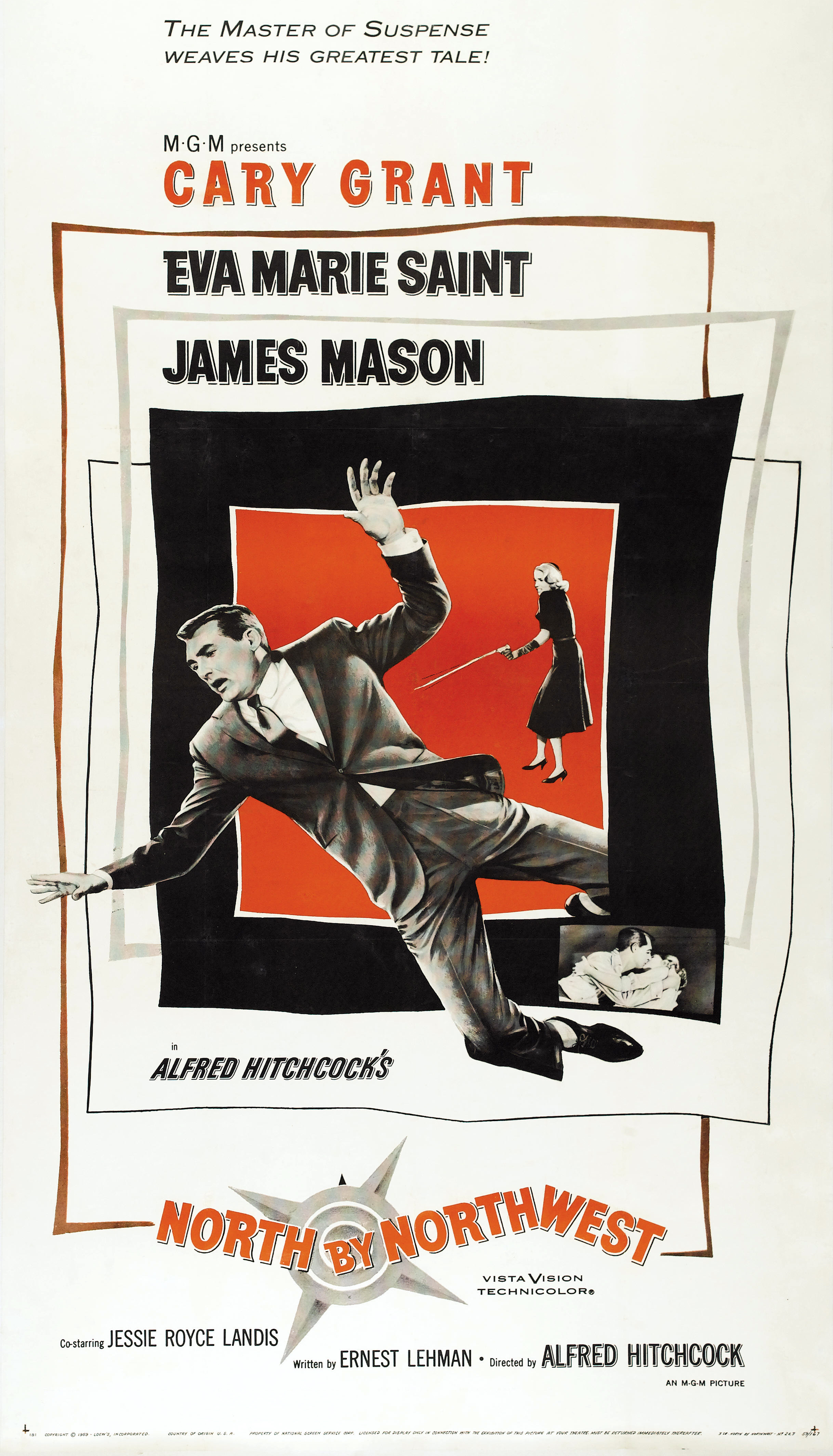

North by Northwest (Alfred Hitchcock, 1959)

There's a famous gaffe in North by Northwest, in the scene in which Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint) shoots Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant). Before she fires the gun, you see a young extra in the background stop his ears against the noise, even though it's supposed to surprise and panic the crowd. It's so obvious a mistake that you wonder how the editor, George Tomasini (who was nominated for an Oscar for the film), could have missed it. The usual explanation is that he couldn't find a way to cut it out, or didn't have footage to replace it. And after all, in the days before home video, would the audience in the theater notice? Even if they did, they would have no easy way to confirm that they had actually seen it. But I have a different suspicion: I think that they showed the goof to Alfred Hitchcock, and that he laughed and left it in. For above all else, North by Northwest is a spoof, a good-natured Hitchcockian jest about a genre that he had virtually invented in 1935 with The 39 Steps: the chase thriller, in which the good guy finds himself on the run, pursued by both the bad guys and other good guys. The ear-plugging kid fits in with the film's general insouciance about plausibility. A couple who climb down the face of Mount Rushmore, she in heels (and later in stocking feet) and he in street shoes? A lavish modern house with a private air strip that seems to be on top of the mountain, only a few hundred yards from the monument? A good-looking man who seems to go unnoticed by the crowds in New York and Chicago and on the train in between, even though his face is on the front page of every newspaper? A beautiful blond woman who shows up just at the right moment to take him in and not only hide him on the train but make love to him? Only a director with Hitchcock's skill and aplomb could take on such a tall tale and make it work, keeping you thoroughly entertained in the process. Of course, he had a good screenplay by Ernest Lehman to work with, along with one of the greatest leading men of all time. He had a leading lady with enough skill to evoke his favorite leading lady, Grace Kelly, without embarrassing herself (as Tippi Hedren came close to doing when she tried). He had Bernard Herrmann's wonderful score, alternately pulse-pounding and romantic, and Robert Burks's cinematography. He had James Mason, Martin Landau, and Jessie Royce Landis as support. I would call it my favorite Hitchcock film, but that's maybe only because I've just seen it, and my ranking will probably change the next time I see Notorious (1946) or Rear Window (1954) again.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)