|

| Jean Marais in Orphée |

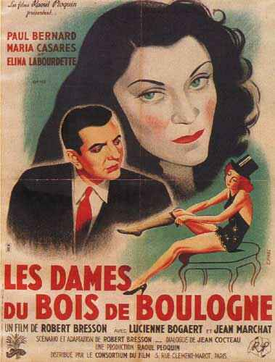

Heurtebise: François Périer

The Princess: María Casares

Eurydice: Marie Déa

The Editor: Henri Crémieux

Aglaonice: Juliette Gréco

The Poet: Roger Blin

Jacques Cégeste: Édouard Dermithe

Director: Jean Cocteau

Screenplay: Jean Cocteau

Cinematography: Nicolas Hayer

Production design: Jean d'Eaubonne

Film editing: Jacqueline Sadoul

Music: Georges Auric

Though it's not as sumptuous as his Beauty and the Beast (1946), Jean Cocteau's Orphée seems to me in some ways the more beautiful film. It embraces ugliness as a foil for beauty in ways that the earlier film doesn't. (As many have noted, the Beast of Cocteau's film is too beautiful a creature to inspire the disgust he presumably was doomed to evoke.) In Orphée the ugliness is that of the modern world, still in the time of the making of the film filled with the rubble of war, such as the bombed-out Saint-Cyr military academy that serves as the film's underworld. So the entire film is a kind of balancing act between antagonistic forces, not just ugliness and beauty or ancient myth and modern reality, but also and especially Eros and Thanatos. It is, of course, dreamlike, not in the cliché surrealist manner of most movie dreams, but in the oddities of its settings: an upstairs bedroom, for example, accessible only by a trapdoor or a ladder outside the window. I'm particularly drawn to the low-tech special effects, created by obvious means: film run backward, rear-screen projection, sets built on an incline. Even if we know how the tricks are done we marvel at the magic they add. Cocteau has de-sentimentalized the Orpheus myth. The marriage of his Orpheus and Eurydice is hardly an ideal one: He's a self-centered crank, and she's a wimp. But by doing so he has made the film's "happy ending" more poignant, as the couple return to life in improved versions and the Princess and Heurtebise (a marvelously imagined character) wander deeper into the underworld. It's an ambiguous fairytale at best.