The brothers Barrymore do some delightful upstaging of each other in Arsène Lupin, with John as the suave duke whom Lionel as the dogged police inspector suspects of being the thief known as Arsène Lupin. There's some sexy business involving Karen Morley as a socialite who may be more than what she seems, and everything culminates in the theft of the Mona Lisa. It's maybe a little more creaky in its joints than is good for it, in the way of early talkies.

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label John Barrymore. Show all posts

Showing posts with label John Barrymore. Show all posts

Sunday, June 2, 2019

Arsène Lupin (Jack Conway, 1932)

The brothers Barrymore do some delightful upstaging of each other in Arsène Lupin, with John as the suave duke whom Lionel as the dogged police inspector suspects of being the thief known as Arsène Lupin. There's some sexy business involving Karen Morley as a socialite who may be more than what she seems, and everything culminates in the theft of the Mona Lisa. It's maybe a little more creaky in its joints than is good for it, in the way of early talkies.

Friday, May 3, 2019

When a Man Loves (Alan Crosland, 1927)

When a Man Loves (Alan Crosland, 1927)

Cast: John Barrymore, Dolores Costello, Warner Oland, Sam De Grasse, Holmes Herbert, Stuart Holmes, Bertram Grassby, Tom Santschi. Screenplay: Bess Meredyth, based on a novel by Abbé Prévost. Cinematography: Byron Haskin. Film editing: Harold McCord. Music: Henry Hadley.

Wednesday, March 27, 2019

Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks, 1934)

Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks, 1934)

Cast: John Barrymore, Carole Lombard, Walter Connolly, Roscoe Karns, Ralph Forbes, Charles Lane, Etienne Girardot, Dale Fuller, Edgar Kennedy. Screenplay: Ben Hecht, Charles MacArthur, based on a play by Charles Bruce Millholland. Cinematography: Joseph H. August. Film editing: Gene Havlick.

Friday, September 21, 2018

Don Juan (Alan Crosland, 1926)

|

| Estelle Taylor and John Barrymore in Don Juan |

Adriana della Varnese: Mary Astor

Lucrezia Borgia: Estelle Taylor

Cesare Borgia: Warner Oland

Count Giano Donati: Montagu Love

Pedrillo: Willard Louis

Mai: Myrna Loy

Marchesia Rinaldo: Hedda Hopper

Marchese Rinaldo: Nigel De Brulier

Donna Isobel: Jane Winton

Leandro: John Roche

Neri: Gustav von Seyffertitz

Director: Alan Crosland

Screenplay: Bess Meredyth; Titles: Walter Anthony, Maude Fulton

Cinematography: Byron Haskin

Art direction: Ben Carré

Film editing: Harold McCord

Music: William Axt, David Mendoza

Alan Crosland's silly action movie Don Juan has two things in its favor. One of them is historical: It was the first film with a synchronized sound track, though it's all music and no dialogue, which would have to wait a year for Crosland's The Jazz Singer. The score is played by no less than the New York Philharmonic. The other is the cast, starting with John Barrymore, first hamming it up in a death scene as Don Juan's father, and then doing some Douglas Fairbanks-style leaping about and sword-fighting as the great seducer. But the female cast is even more interesting, with Mary Astor teamed again with her Beau Brummel (Harry Beaumont, 1924) co-star and former lover Barrymore, as well as some actresses who went on to different sorts of fame. Before she became Hollywood's favorite wife and/or mother, Myrna Loy was often cast as a vamp or a sinister type; here she slinks around as Lucrezia Borgia's lady-in-waiting, spying and tattling and stealing scenes from Estelle Taylor's Lucrezia. And before she became one of Hollywood's two most feared purveyors of gossip -- the other being Louella Parsons -- Hedda Hopper had a long career as a supporting actress; here she's the Marchesia Rinaldo, who kills herself when her husband discovers her affair with Don Juan. As for the rest of the movie, it's predictably junky, "explaining" Don Juan's treatment of women as a product of witnessing as a child his father being murdered by a cast-off lover. This psychological trauma is, I guess, supposed to make us believe that Juan has been cured of his hypersexuality by the love of a pure woman, Astor's Adriana della Varnese, with whom he literally rides off into the sunset at the end of the film.

Friday, September 7, 2018

Grand Hotel (Edmund Goulding, 1932)

|

| Greta Garbo and John Barrymore in Grand Hotel |

Baron Felix von Geigern: John Barrymore

Flaemmchen: Joan Crawford

General Director Preysing: Wallace Beery

Otto Kringelein: Lionel Barrymore

Dr. Otternschlag: Lewis Stone

Senf: Jean Hersholt

Suzette: Rafaela Ottiano

Pimenov: Ferdinand Gottschalk

Meierheim: Robert McWade

Zinnowitz: Purnell Pratt

Director: Edmund Goulding

Screenplay: Béla Balász, William Absalom Drake, Edgar Allan Woolf

Based on a novel by Vicki Baum and a play by William Absalom Drake

Cinematography: William H. Daniels

Art direction: Cedric Gibbons

Film editing: Blanche Sewell

Costume design: Adrian

Music: Charles Maxwell

The criticism most often made of Grand Hotel is that its performances are hammy. Greta Garbo's face, even in medium shots, is never at rest, eyebrows arching, nostrils flaring, lips curling and pouting. John Barrymore poses shamelessly, always managing to find a way to lift his chin the better to display his celebrated profile. Joan Crawford, whose best feature was her eyes, manages to open them so wide you'd think she was playing opposite an optometrist instead of Wallace Beery and the Barrymore brothers. One conventional explanation for all of this preening and camera-hogging is that it's inherent to an all-star cast in which every star wants to shine brightest. Another is that all of the stars had been in silent films, where the absence of sound puts a premium on telegraphing emotions visually, and 1932 was still early enough that actors weren't fully accustomed to letting the dialogue do the work. But I think director Edmund Goulding deserves most of the blame. Compare, for example, the performance given by Garbo under the direction of George Cukor four years later in Camille: She has learned to let the dialogue and the camera do most of the work, so the tics and mannerisms have vanished. Cukor also directed the Barrymore brothers in Dinner at Eight just a year after Grand Hotel, and while their hamming is still a bit excessive, Cukor knows how to integrate it into another all-star ensemble. And no director got better performances out of Crawford than Cukor did in her sharply contrasting roles in The Women (1939) and A Woman's Face (1941). But I come not to praise Cukor or really to bury Goulding, except to note that for many years, Grand Hotel was the only best picture Oscar winner without a corresponding nomination for its director.* Still, it's a very entertaining movie, cramming a lot of characters into a small space and providing some real intrigue and even action -- it's the only film I can recall in which someone is beaten to death with a telephone. It looks good, too, for its age: Cedric Gibbons's art deco sets are spiffy and Adrian's gowns and negligees and frocks are sexy.

*Oscar trivia footnote: In fact, Grand Hotel remains the only best picture winner to receive no nominations in any other category. As for the picture-director correlation, Grand Hotel held on to that distinction until the 1989 Oscars, when Driving Miss Daisy was named best picture but Bruce Beresford went unnominated. And it didn't happen again until 2012 when Ben Affleck was passed over for directing Argo.

Tuesday, June 19, 2018

Beau Brummel (Harry Beaumont, 1924)

|

| Mary Astor and John Barrymore in Beau Brummel |

Lady Margery Alvanley: Mary Astor

The Prince of Wales: Willard Louis

Lady Hester Stanhope: Carmel Myers

Duchess of York: Irene Rich

Mortimer: Alec B. Francis

Lord Alvanley: William Humphrey

Lord Stanhope: Richard Tucker

Lord Byron: George Beranger

Director: Harry Beaumont

Screenplay: Dorothy Farnum

Based on a play by Clyde Fitch

Cinematography: David Abel

Film editing: Howard Bretherton

The slow, stagy, and occasionally cheesy-looking costume drama was the film that lured John Barrymore away from Broadway to Hollywood. It's about the rise and fall of George Bryan Brummel (usually spelled with two l's) in the court of the Prince of Wales, later Prince Regent and then George IV. Barrymore gets to load on the old age makeup -- which makes him look startlingly like his brother, Lionel -- as the film goes on. The supporting cast plays a gaggle of semihistorical figures who are mostly there for atmosphere; I was surprised, for example, to discover that the rather ordinary fellow limping around in the background was supposed to be Lord Byron. None of the film's history can be trusted, of course, so there's really not much to be said about it other than that Barrymore chews the scenery with aplomb and that the 18-year-old Mary Astor is pleasant to look at.

Monday, February 20, 2017

Svengali (Archie Mayo, 1931)

|

| Marian Marsh, Bramwell Fletcher, and John Barrymore in Svengali |

Trilby O'Farrell: Marian Marsh

The Laird: Donald Crisp

Billee: Bramwell Fletcher

Madame Honori: Carmel Myers

Gecko: Luis Alberni

Monsieur Taffy: Lumsden Hare

Bonelli: Paul Porcasi

Director: Archie Mayo

Screenplay: J. Grubb Alexander

Based on a novel by George L. Du Maurier

Cinematography: Barney McGill

Art direction: Anton Grot

Film editing: William Holmes

Music: David Mendoza

George Du Maurier's 1894 novel was called Trilby, as were many of the stage adaptations and early silent film versions. But if you cast John Barrymore as the sinister hypnotist, you almost have to call your film Svengali. It's one of Barrymore's juiciest movie performances, but it surprisingly didn't earn him an Oscar nomination -- an honor he never received. To add to the irony, the best actor Oscar that year went to his brother Lionel for A Free Soul (Clarence Brown, 1931), and one of the actors who did receive a nomination was Fredric March for playing Tony Cavendish, an obvious caricature of John Barrymore, in The Royal Family of Broadway (George Cukor and Cyril Gardner, 1930). Though Barrymore's Svengali doesn't particularly deserve an award, it's the best thing about the film aside from the sets by Anton Grot that were influenced by German expressionism and did earn Grot a nomination, as did cinematographer Barney McGill's filming of them. Like many early talkies, Svengali is slackly paced, as if director Archie Mayo, who learned his craft in the silent era, was still slowing things down so title cards could be placed at the appropriate intervals. It also has some problems of tone: Svengali is not quite the sinister monster you expect him to be from his reputation as an archetype of masterful control. In the beginning he's the butt of horseplay from some of his fellow Paris bohemians, the painters known as The Laird and Taffy, who decide he doesn't bathe often enough and dump him into a bathtub. We know his potential for evil after he causes Madame Honori to commit suicide, but even her character is played for comedy before her untimely end. In this adaptation, by J. Grubb Alexander, the plot revolves around Svengali's manipulation of Trilby, an artist's model whose potential as a singer -- even though she can't quite carry a tune -- he deduces from the shape of her mouth. He uses his hypnotic powers to turn her into a diva, though the one performance we see from her, a bit of the Mad Scene from Lucia di Lammermoor, doesn't merit the ovation it receives -- perhaps he hypnotized the audience, too. But control of Trilby comes at a cost: Svengali's health begins to decline, and Trilby's career along with it, until at the end they both die as she performs in a nightclub in Cairo, second-billed to a troupe of belly-dancers. Only the lovestruck young artist known as "Little Billee," who has devoted his life to tracking Trilby in hopes of winning her back, is there to witness her end. Thanks to Barrymore, and some good support from character actors like Luis Alberni, who plays Svengali's assistant with the improbable name Gecko, Svengali is never unwatchable, and it mostly avoids the antisemitic notes that many have observed in the character, who is said to have mysterious origins, perhaps in Poland, in the novel and its adaptations.

Friday, December 9, 2016

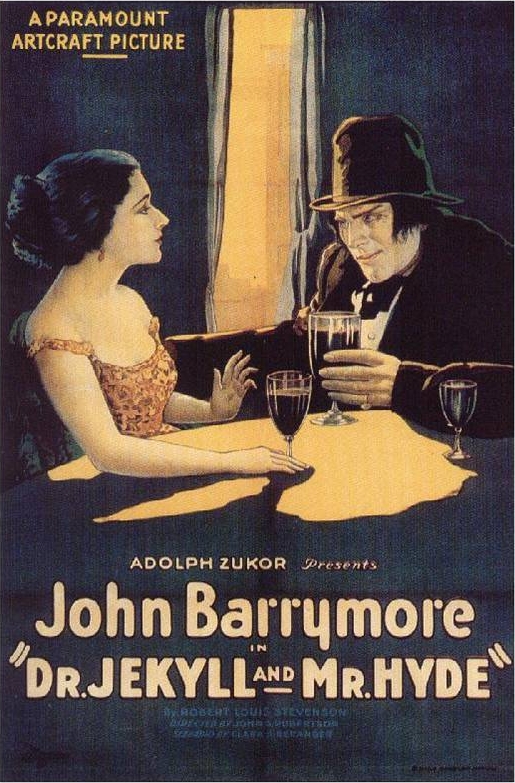

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (John S. Robertson, 1920)

Almost from the moment that Robert Louis Stevenson published his novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in 1886, theatrical producers were snapping it up for adaptation. It was a great vehicle for ham actors who relished the transformation scenes, as long as it could be spiced up a little with a little sex -- the novella is more interested in the psychology of Jekyll/Hyde than in the lurking-horror and damsels-in-distress elements added to most stage and screen versions. There were several film versions before John Barrymore, the greatest of all ham actors, took on the role in 1920. It's an adaptation by Clara Beranger of the first major stage version by Thomas Russell Sullivan, who added a central damsel in distress as Jekyll's love. She's called Millicent Carewe (Martha Mansfield) in the film, which also adds a "dance hall girl" named Gina (Nita Naldi) to the mix. Mansfield is bland and Naldi is superfluous, though rather fun to watch when she goes into her "dance," which consists of a lot of hip-swinging and arm-waving. Barrymore, however, is terrific, giving his transformation into Hyde everything he's got in the way of contortions of face and body. Though the screenplay makes much of the distinction between the virtuous Jekyll and the dissolute Hyde, Barrymore manages to suggest the latency of Hyde in Jekyll even before he swallows the sinister potion -- a reversion to Stevenson's original, in which Jekyll is not quite the upstanding fellow the adaptations tried to make him.

Thursday, July 21, 2016

Dinner at Eight (George Cukor, 1933)

It has always struck me as odd that Grand Hotel (Edmund Goulding, 1932) won the 1931-32 best picture Oscar, when Dinner at Eight, a similarly constructed all-star affair, was shut out of the nominations for the 1932-33 awards. Dinner at Eight is much the better picture, with a tighter, wittier script (by Frances Marion and Herman J. Mankiewicz, with additional dialogue by Donald Ogden Stewart) and a cast that includes three of the Grand Hotel stars: John Barrymore, Lionel Barrymore, and Jean Hersholt. Granted, it doesn't have Greta Garbo and Joan Crawford, but it has Jean Harlow and Marie Dressler at their best, and a director who knows how to keep things perking. (Cukor was, at least, nominated for Little Women instead.) It also has one of the great concluding scenes in movies, when everyone goes in to dinner and Kitty (Harlow) tells Carlotta (Dressler) that she's been reading a book, bringing the formidable bulk of Dressler to a lurching halt. (You've seen it a dozen times in clip shows of great movie moments. If not, go watch the movie.) Granted, too, that Dinner at Eight is not quite sure whether it's a comic melodrama or a melodramatic comedy, dealing as it does with the effects of the Depression on the rich and famous, with marital infidelity and suicide (both of them in ways that the Production Code would soon preclude -- as it would Harlow's barely there Adrian gowns). And there's some over-the-top hamming from both Barrymores. In fact, the performances in general are pitched a little too high, a sign that Cukor hadn't quite yet left his career as a stage director behind and discovered that a little less can be a lot more in movies. Nevertheless, it's a more-than-tolerable movie, and a damn sight better than the year's best picture winner, the almost unwatchable Cavalcade (Frank Lloyd).

Sunday, January 17, 2016

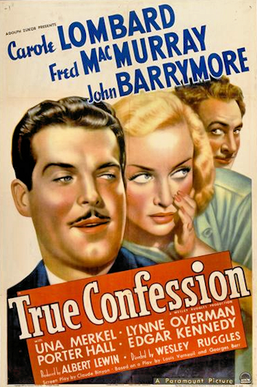

True Confession (Wesley Ruggles, 1937)

A somewhat too frantic screwball comedy, True Confession plays fast and loose not only with the legal profession but also to an extent with the careers of its stars. Fred MacMurray plays Kenneth Bartlett, a lawyer who insists on defending only those he thinks are really innocent, which gives him some trouble when his wife, Helen (Carole Lombard), goes on trial for murder. She's a would-be writer who can't always be trusted to tell the truth, so even though she didn't commit the crime, she winds up saying she did and pleading self-defense. Meanwhile, the trial is being watched by Charley Jasper (John Barrymore), an alcoholic loon who knows who really did the deed. None of these people make much sense, especially Barrymore, who seems at times to be reprising his earlier, far more successful performance as Oscar Jaffe opposite Lombard's Lily Garland (aka Mildred Plotka) in Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks, 1934). Alcohol had taken a serious toll on Barrymore, who was 55 when he made this film; he looks 70. Lombard was better, more controlled in her comic flights in Twentieth Century, too. Here she verges on grating at times. Comparisons are seldom fair, but it has to be said that the difference between the two films has to be that the earlier and better one was directed by Hawks from a screenplay by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, and True Confession was directed by Wesley Ruggles from a screenplay by Claude Binyon based on a French farce. Still, there's some fun to be had here, and the cast includes such stars from the golden age of character actors as Una Merkel being giddy, Porter Hall being irascible, Edgar Kennedy doing multiple face-palms, and Hattie McDaniel playing one of her always watchable (if regrettable) roles as the maid.

Sunday, November 29, 2015

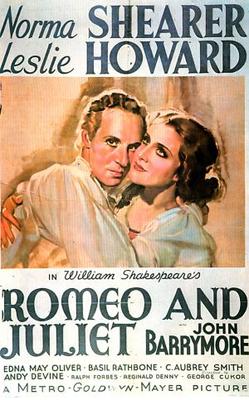

Romeo and Juliet (George Cukor, 1936)

If Shakespeare's Juliet could be played, as it was in its first performances, by a boy, then why shouldn't she be played by 34-year-old Norma Shearer? Truth be told, I don't find Shearer's performance that bad: She lightens her voice effectively and her girlish manner never gets too coy. It also helps that William H. Daniels photographs her through filters that soften the signs of aging: She looks maybe five years younger than her actual age, if not the 20 years younger that the play's Juliet is supposed to be. I'm more bothered by the balding 43-year-old Leslie Howard as her Romeo, though he had the theatrical training that makes the verse sound convincing in his delivery. And then there's the 54-year-old John Barrymore as Mercutio, who could be Romeo's fey uncle but not his contemporary. In fact, Barrymore's over-the-top performance almost makes this version of the play a must-see -- we miss him more than we do most Mercutios after his death. Edna May Oliver's turn as Juliet's Nurse is enjoyable, if a bit of a surprise: She usually played eccentric spinsters like Aunt Betsy Trotwood in David Copperfield (George Cukor, 1935) or sour dowagers like Lady Catherine de Bourgh in Pride and Prejudice (Robert Z. Leonard, 1940). In the play, the Nurse rarely speaks without risqué double-entendres, but most of them have been cut in Talbot Jennings's adaptation, thus avoiding the ridiculous spectacle of Shakespeare being subjected to the Production Code censors. (Somehow the studio managed to slip in Mercutio's line, "the bawdy hand of the dial is now upon the prick of noon.") Some of the other pleasures of the film are camp ones, such as Agnes deMille's choreography for the ball, along with the costume designs by Oliver Messel and Adrian, which evoke early 20th-century illustrators like Walter Crane or Maxfield Parrish. No, this Romeo and Juliet won't do, except as a representation of how Shakespeare's play was seen at a particular time and place: a Hollywood film studio in the heyday of the star system. In that respect, it's invaluable.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)