A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Sacha Vierny. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Sacha Vierny. Show all posts

Friday, January 6, 2017

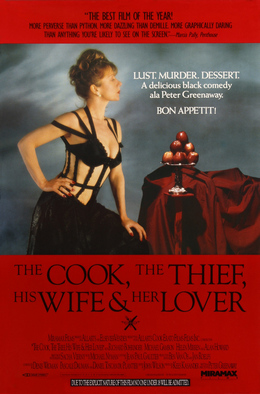

The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (Peter Greenaway, 1989)

I have to imagine some naive young person whose idea of outrageous filmmaking extends no further than the work of David Lynch or Quentin Tarantino, and who knows Helen Mirren only as the Oscar winner for The Queen (Stephen Frears, 2006) and as a dame of the British Empire, coming across The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover. It's a full-fledged assault on conventional movies, so provocative that it feels like it was made a decade or so earlier, when filmmakers were testing the limits, and not in the comparatively timid 1980s. The title itself sounds like the setup for a dirty joke, but writer-director Peter Greenaway delivers much more than that. The Cook (Richard Bohringer) runs the kitchen at a fancy restaurant that has been taken over by the Thief (Michael Gambon) and his retinue of thugs, who make a mess of things every night. Meanwhile, the Thief's Wife (Mirren) is carrying on an affair with her bookstore-owner Lover (Alan Howard) in every nook and cranny of the restaurant they can find. When the Thief finds out, the lovers hide from him at the book depository, but the Thief finds and murders him by stuffing pages from books down his throat. Eventually, the Wife, with the culinary assistance of the Cook, takes revenge in a most unappetizing way. The whole thing is played in the most over-the-top fashion imaginable, but the skill and daring of the actors makes it compelling. Gambon makes the Thief so colossally vulgar that we laugh almost as much as we cringe. Mirren and Howard are naked for great stretches of the film, but the effect is less erotic than you might think; instead, it emphasizes their vulnerability. Add to that the extraordinary production design of Ben van Os and Jan Roelfs, the sometimes kinky costume design by Jean-Paul Gaultier, the cinematography of Sacha Vierny, and the musical score by Michael Nyman, and what you have is undeniably a work of art -- perverse and sometimes extremely unpleasant, but decidedly unforgettable.

Friday, January 15, 2016

Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959)

I remember the long dorm-room discussion after my friends and I saw this film for the first time, so I was surprised on returning to it after so many years how conventional the elements we talked about now seem. The extended use of documentary clips at the beginning of the film, with the voiceover by the lovers (Emmanuelle Riva and Eiji Okada) arguing about whether she had really seen anything in Hiroshima, seemed to us a bafflingly random way to start a movie. The jump cuts into and out of flashbacks confused us. What, we argued, did it signify that their entwined bodies, seemingly covered with ashes, then began to glow? (Today, I'm afraid some sarcastic voice will pipe up to say, "They've been glitter-bombed.") Why does she refer to her Japanese lover as "you" when she's actually talking about the German she loved during the war? Is the movie really about sleeping with the enemy? Doesn't it trivialize the horror of Hiroshima to bring it down to the level of the background for a love affair? Today, we'd regard those questions as naive, and I'm certain we wouldn't be confused by the film's structure, which is a way of saying that Resnais and his screenwriter, Marguerite Duras, really did succeed in revolutionizing movies. But if no one is startled by jump cuts or unconventional narrative devices today, there remains a raw immediacy about the film that no subsequent imitators have ever quite succeeded in equaling. Much credit also has to go to the score by Georges Delerue and Giovanni Fusco, and to the editing by Michio Takahashi and Sacha Vierny.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)