|

| Poster with the British title for The Great McGinty |

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Akim Tamiroff. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Akim Tamiroff. Show all posts

Wednesday, January 11, 2017

The Great McGinty (Preston Sturges,1940)

Saturday, May 7, 2016

Mr. Arkadin (Orson Welles, 1955)

|

| Michael Redgrave in Mr. Arkadin |

Guy Van Stratten: Robert Arden

Mily: Patricia Medina

Burgomil Trebitsch: Michael Redgrave

Jakob Zouk: Akim Tamiroff

Sophie: Katina Paxinou

The Professor: Mischa Auer

Thaddeus: Peter van Eyck

Raina Arkadin: Paola Mori

Baroness Nagel: Suzanne Flon

Director: Orson Welles

Screenplay: Orson Welles

Cinematography: Jean Bourgoin

Art direction: Orson Welles

Film editing: Renzo Lucidi, William Morton, Orson Welles

Music: Paul Misraki

"What if?" is the question that haunts every Orson Welles film after Citizen Kane (1941). What if Welles had had the financial, production, and distribution support for his films? Of none of them is the question more appropriate than Mr. Arkadin, which was edited by other hands than Welles's and not even shown in the United States until 1962, and at one point was said to exist in at least seven different versions. In 2006, the Criterion Collection released a three-DVD set that edited together all of the existing English-language versions of the film, following what was known of Welles's original plan, along with his comments on some of the other versions that had been released. It's probably as close as we're going to get to what the director had in mind. So what if Mr. Arkadin had been under Welles's control all along? Would we have a more coherent narrative and style? Would the protagonist, Guy Van Stratten, have been played by a more skilled actor than Robert Arden? (It's a role that would have been perfect for someone like William Holden.) Would Welles have called on the best makeup artists to provide him with a more convincing prosthetic nose and a wig and beard whose edges don't show? Would the function and the fate of Patricia Medina's character, Mily, have been clearer? And does any of this really matter? For what we have here, despite Welles's later description of the film (or its handling) as a "disaster," is one of the most fascinating works in his storied, troubled career. There are sequences that are haunting, even if their purpose in the film is unclear, such as the procession of the penitentes, who in their tall, pointed hoods look like exactly what Mily mistakes them for: "crazy ku kluxers." Or the Goyaesque masks at Arkadin's ball. Or the sequence of truly wonderful cameo performances, including a hair-netted Michael Redgrave as the junk dealer Burgomil Trebitsch, who keeps trying to sell Van Stratten a busted telescope (which he pronounces "telly-o-scope"). Or Mischa Auer as the proprietor of a flea circus. Or Katina Paxinou as a Mexican (?) woman named Sophie. And then there's one of Welles's most celebrated speeches, perhaps second only to his "cuckoo clock" monologue in The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949), in which Arkadin tells the fable of the scorpion and the frog. Though analogues have been found in folklore around the world, this particular formulation of it seems to have been Welles's own:

This scorpion wanted to cross a river, so he asked the frog to carry him. No, said the frog, no thank you. If I let you on my back you may sting me and the sting of the scorpion is death. Now, where, asked the scorpion, is the logic in that? For scorpions always try to be logical. If I sting you, you will die. I will drown. So, the frog was convinced and allowed the scorpion on his back. But, just in the middle of the river, he felt a terrible pain and realized that, after all, the scorpion had stung him. Logic! Cried the dying frog as he started under, bearing the scorpion down with him. There is no logic in this! I know, said the scorpion, but I can't help it -- it's my character.Perhaps it was Welles's character that betrayed him into making movies that flopped but turned into classics.

Friday, April 22, 2016

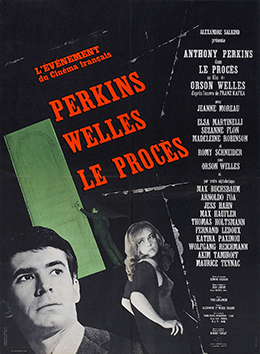

The Trial (Orson Welles, 1962)

There may be sensibilities more different from each other than those of an exiled Midwestern bon vivant and a consumptive Middle European Jew, but they rarely come together in a work of art the way they did in Orson Welles's version of Franz Kafka's The Trial. It was made in that fertile middle period of Welles's career that also saw the creation of Touch of Evil (1958) and Chimes at Midnight (1965), and it holds its own against those two landmarks in the Welles oeuvre. In the end, of course, the Wellesian sensibility dominates, the American tendency to affirmation overcoming (barely) Kafka's pessimism: Welles's Josef K. (Anthony Perkins) is rather more assertive than Kafka's protagonist. He doesn't succumb "Like a dog!" to his assailants but defies them. That said, Perkins, now carrying the indelible stamp of Norman Bates into all his roles, is superlative casting: We can believe that he's guilty -- even if we never find out what his supposed crime is -- while at the same time we sympathize with his plight. The real triumph of the film is in finding the settings in which to stage K.'s ordeal, ranging from K.'s stark, low-ceilinged apartment to bleak modern high-rise apartment and office buildings, to ornate beaux arts exteriors, to the labyrinthine courts of the law. The film was shot in the former Yugoslavia, in Italy, and in the abandoned Gare d'Orsay in Paris. Welles chose a novice, Edmond Richard, who had never shot a feature film, as his cinematographer. Richard went on to shoot Chimes at Midnight, too, as well as some of Luis Buñuel's best films, including The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). The cast includes Jeanne Moreau, Romy Schneider, Elsa Martinelli, and Akim Tamiroff, with Welles himself playing the role of Hastler, K.'s attorney, after failing to persuade Jackie Gleason or Charles Laughton to take the part. The Trial is probably longer and slower than it needs to be, and there is some inconsistency of style: The scenes involving Hastler, his mistress (Schneider), and K. are shot with more extreme closeups than the rest of the film, where the sets tend to overwhelm the human figures. And the ending, with its explosion followed by a rather wispy mushroom cloud, is a little too obviously an attempt to bring a story written during World War I into the atomic era. Some think it's a masterpiece, but I would just rank it as essential Welles -- which may or may not be the same thing.

Tuesday, March 29, 2016

Touch of Evil (Orson Welles, 1958)

Saturday, October 3, 2015

Alphaville (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965)

|

| Eddie Constantine in Alphaville |

Natacha von Braun: Anna Karina

Henri Dickson: Akim Tamiroff

Professor von Braun: Howard Vernon

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Screenplay: Jean-Luc Godard

Cinematography: Raoul Coutard

Production design: Pierre Guffroy

Music: Paul Misraki

I think Alphaville may have been responsible for my former distaste for Godard movies: When I saw it on its first American run -- probably at that temple of Harvard hip, the Brattle Theater -- I couldn't figure out why anyone would make a sci-fi movie starring an American-French B-movie actor as a trenchcoated secret agent in a future that looked a lot like contemporary Paris. Or why the beautiful Natacha Von Braun should fall in love with anyone who looks like Eddie Constantine -- the apparent survivor of a close encounter with a cheese grater. But time and experience teach you a lot about what's really witty, and Alphaville is that. Yes, it's a spoof on both sci-fi and spy movies, with Paul Misraki's score providing the familiar dun-dun-DUNN! underscoring of suspenseful moments as Lemmy Caution slugs and shoots his way out of ridiculously staged confrontations. But how many spoofs have we seen that fall flat because they're so self-conscious about their spoofery? Godard's spoof succeeds because Constantine, Karina, and that great slab of Armenian ham Akim Tamiroff take their roles so seriously. Like most Godard movies, it's often absurdly talky, but the talk is provocative. And even though it seems to be designed to make a point about the way contemporary design and architecture have a way of alienating us from the human, it doesn't hammer the point. My one complaint in this recent viewing is that Turner Classic Movies showed a muddy print in which the subtitles had their feet cut off.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)