A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Barbara Loden. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Barbara Loden. Show all posts

Friday, October 4, 2019

Wanda (Barbara Loden, 1970)

Wanda (Barbara Loden, 1970)

Cast: Barbara Loden, Michael Higgins, Dorothy Shupenes, Peter Shupenes, Jerome Thier, M.L. Kennedy, Milton Gittleman, Charles Dosinan, Jack Ford, Rozamond Peck, Frank Jourdano. Screenplay: Barbara Loden. Cinematography: Nicholas T. Proferes. Film editing: Nicholas T. Proferes.

If Barbara Loden had made other films, would Wanda be as celebrated as it is today? Would it, for example, have found its way into the Library of Congress's National Film Registry? Or would its raw, sometimes clunky, defiantly unpolished filmmaking have doomed it to obscurity as the amateur work of an actress best known for secondary roles in movies made by her ex-husband, Elia Kazan? Wanda is, like its title character, a bit of a mess. Wanda herself is barely a character; she's more of a creature of impulse, bolting a dead-end marriage in an American Rust Belt town, allowing herself to get picked up by strange men, and eventually being coerced into going along on a road trip that ends in a scheme to rob a bank. But as a writer-director, Loden is impulsive, too. So there's a cheesy, rundown religious theme park we can shoot in? Fine, let's do it, and maybe have Wanda's partner in crime, Mr. Dennis, meet his father there as she explores the fake catacombs. The scene does nothing to advance the story or even to illuminate the characters, but is there as a sort of quirkiness for quirkiness's sake. There's also a sort of calm-before-the-storm interlude before the abortive bank robbery scene, in which Wanda and Mr. Dennis picnic and watch a model airplane doing loop-the-loops. And yet, Wanda somehow works because Loden has some of the best instincts of a filmmaker, exemplified early in the movie by the long shots of Wanda, dressed in white, walking past gray slagheaps, giving her an entirely ironic image of innocence and purity. Loden represses any instinct to mock the depressed milieu in which Wanda exists, but lets the tackiness and bad taste that surround her speak for themselves. She also wisely resisted the ending originally planned for the film, in which Wanda would be arrested as an accessory for the bank robbery, but leaves her protagonist looking sad and lost in a bar where country musicians are playing. I don't feel as enthusiastic about Wanda as some do, but it makes me wish that Loden had lived to make more films.

Monday, August 22, 2016

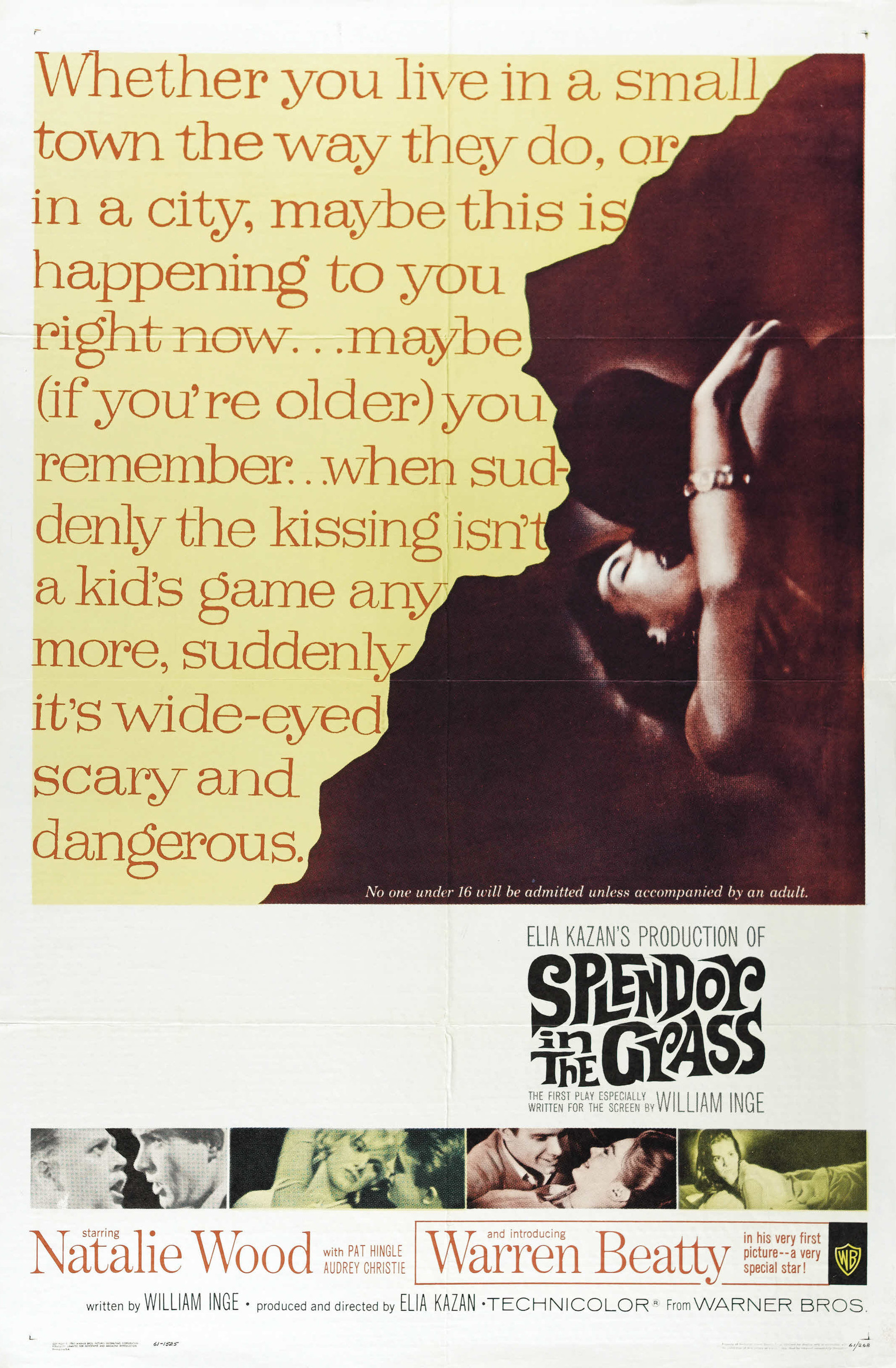

Splendor in the Grass (Elia Kazan, 1961)

This overheated melodrama, released the year after the introduction of the Pill, could almost be a valedictory to the 1950s. Deanie Loomis (Natalie Wood) and Bud Stamper (Warren Beatty) are two hormone-drenched Kansas teenagers in 1928 -- though the attitudes toward sex were still prevalent thirty years later -- unable to find an outlet for the passions they are told they should repress. He is under the sway of a bullying, motormouthed father (Pat Hingle in an over-the-top performance that's alternately frightening and ludicrous), while she has a frigid, convention-ridden mother (Audrey Christie). She goes mad and is sent to a mental hospital. He goes to Yale and flunks out. Such are the consequences of not having sex. The truth is, Splendor in the Grass is not quite as silly as this summary makes it sound. Kazan's direction is, as so often, actor-centered rather than cinematic: The performances of the four actors mentioned give it a lot of energy that at least momentarily overrides any reservations I have about the psychological plausibility of William Inge's screenplay, which won an Oscar. There's also Barbara Loden as Bud's wild flapper sister, and Zohra Lampert as the earthy Italian woman Bud winds up marrying. In the end, the movie becomes almost a documentary of a moment in American filmmaking, when censorship was beginning to lose ground, and things previously unmentionable, like abortion, became at least marginally acceptable. The film itself could almost serve as an indictment of the attitudes that produced the Production Code, which hamstrung American movies from 1934 to 1968. What distinction the movie has other than as a showcase for performances comes from Boris Kaufman's cinematography, Richard Sylbert's production design, and Gene Milford's editing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)