A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Boris Kaufman. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Boris Kaufman. Show all posts

Monday, August 22, 2016

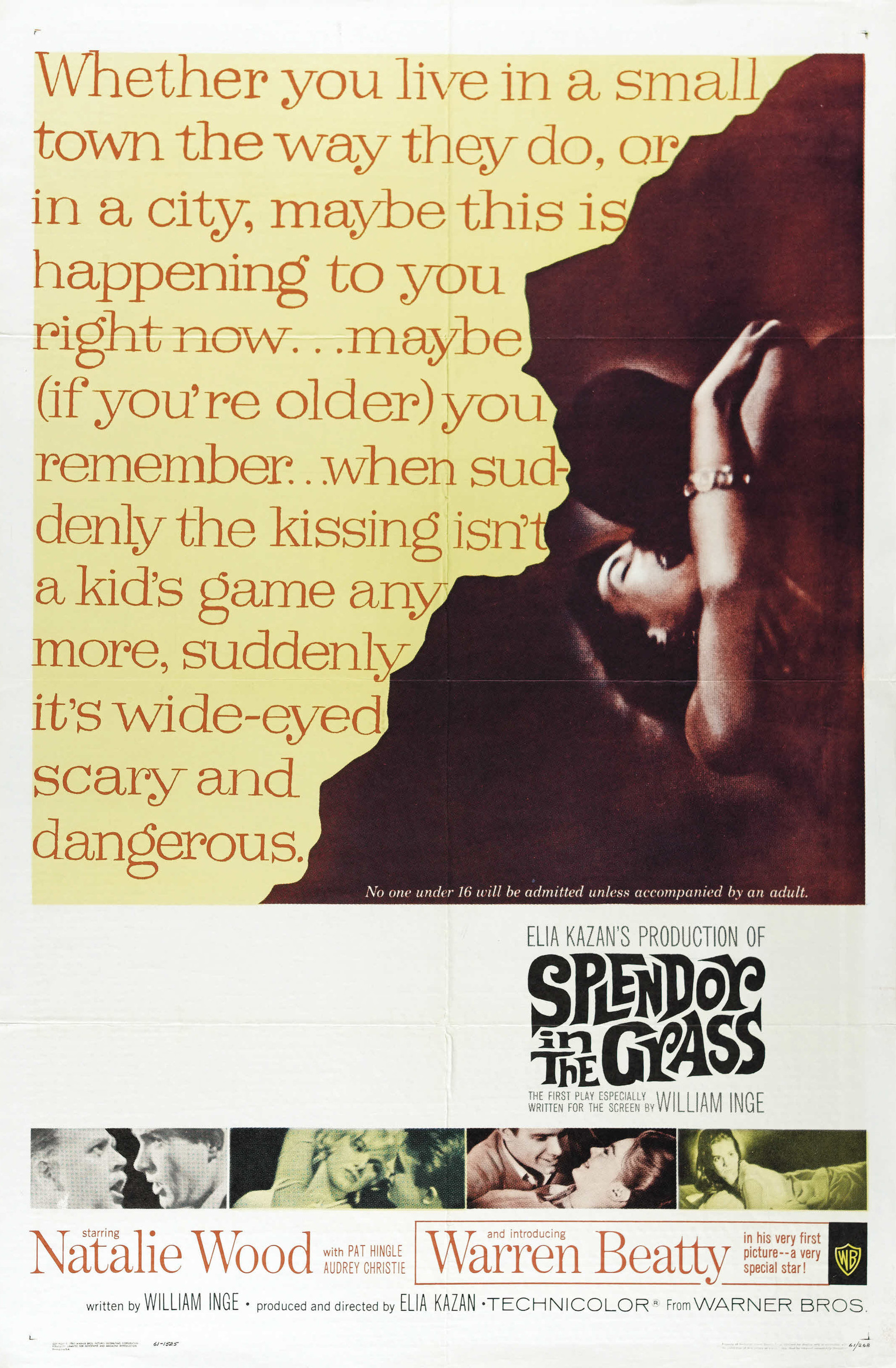

Splendor in the Grass (Elia Kazan, 1961)

This overheated melodrama, released the year after the introduction of the Pill, could almost be a valedictory to the 1950s. Deanie Loomis (Natalie Wood) and Bud Stamper (Warren Beatty) are two hormone-drenched Kansas teenagers in 1928 -- though the attitudes toward sex were still prevalent thirty years later -- unable to find an outlet for the passions they are told they should repress. He is under the sway of a bullying, motormouthed father (Pat Hingle in an over-the-top performance that's alternately frightening and ludicrous), while she has a frigid, convention-ridden mother (Audrey Christie). She goes mad and is sent to a mental hospital. He goes to Yale and flunks out. Such are the consequences of not having sex. The truth is, Splendor in the Grass is not quite as silly as this summary makes it sound. Kazan's direction is, as so often, actor-centered rather than cinematic: The performances of the four actors mentioned give it a lot of energy that at least momentarily overrides any reservations I have about the psychological plausibility of William Inge's screenplay, which won an Oscar. There's also Barbara Loden as Bud's wild flapper sister, and Zohra Lampert as the earthy Italian woman Bud winds up marrying. In the end, the movie becomes almost a documentary of a moment in American filmmaking, when censorship was beginning to lose ground, and things previously unmentionable, like abortion, became at least marginally acceptable. The film itself could almost serve as an indictment of the attitudes that produced the Production Code, which hamstrung American movies from 1934 to 1968. What distinction the movie has other than as a showcase for performances comes from Boris Kaufman's cinematography, Richard Sylbert's production design, and Gene Milford's editing.

Monday, July 4, 2016

L'Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934)

L'Atalante is one of those near-universally acclaimed film masterpieces that failed theatrically on their first release and were rediscovered and re-evaluated more than a decade later. But it's also one of those films that young contemporary movie lovers may not "get" on first viewing today. I remember my own reaction to films like The Rules of the Game (Jean Renoir, 1939) and L'Avventura (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960), movies that didn't fit what I expected from being raised on energetic, plot-driven, star-centered American movies. Melancholy and irony are not widely praised American values, although lord knows we have plenty of it in the best American literature. They surfaced for a time in the best American films of the 1970s, but have been driven back into the underground by the blockbuster mentality. There was a time, even after the great cinematic awakening of the '70s when I found myself resenting film critics for their inability to appreciate popular movies I enjoyed: "Critics see too many movies to enjoy them," I sniffed. But the truth is, the more movies you see, the more you're able to appreciate those that don't walk the line, that don't instantly gratify the hunger for plot resolution, for spectacle, for something that sends you out of the theater blissfully untroubled by thought. L'Atalante confused and bored its contemporary viewers, but today those of us who love it do so because it seems to us alternately tender and brutal, simultaneously comic and touching, and, taken as a whole, one of the few movies that successfully transport us to a time and place and a company of human beings we have never found ourselves in the middle of before. It is also, despite years of mishandling and cutting and botched attempts at restoration, one of the most technically dazzling films ever made. The performances -- by Michel Simon as the rather gross Père Jules, Dita Parlo and Jean Dasté as the young couple trying to start married life on a cramped river barge, and Gilles Margaritis as the madcap peddler who almost wrecks their marriage -- are extraordinary. Cinematographer Boris Kaufman overcame the severe limitations of filming scenes in the cramped quarters below-decks as well as open-air scenes for which the weather refused to cooperate. Vigo and Kaufman stage visual compositions that have a freshness that never seems arty. And who can ever forget Simon's Père Jules clambering aboard the barge with a kitten on his shoulders? Every corner of L'Atalante is filled with life.

Wednesday, June 15, 2016

On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)