|

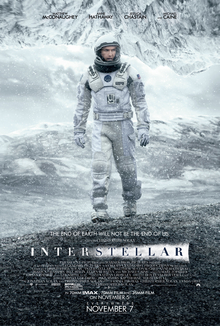

| Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz in The Fountain |

I don't know why Darren Aronofsky's film is called The Fountain, unless Terrence Malick had already reserved The Tree of Life for his 2011 film. There's no fountain of significance in Aronofsky's movie unless it's the Tree itself and the viscous ooze it secretes. Actually, it's worth comparing the two films because both belong to a peculiarly overreaching genre of metaphysical-speculation movies. Malick's works better because it is grounded in a vividly actual portrait of growing up, whereas Aronofsky centers his film on a rather melodramatic story about a research scientist (Hugh Jackman) looking for a cure for the brain tumor that is killing his wife. This story dovetails awkwardly into a story the wife, nicely played by Rachel Weisz, is writing about a 16th-century conquistador's search for the Tree of Life at the behest of the queen of Spain (also Weisz). The Fountain begins in the middle of that story, with an Indiana Jones-like sequence of the conquistador (also Jackman) hacking through the jungle and battling Mayan warriors in his quest. But wait, there's a third story, in which Jackman is now a futuristic spaceman traveling in a transparent sphere -- I couldn't help thinking of Glinda the Good Witch -- along with the Tree itself, whose secrets he is attempting to uncover. No, I don't get it either. Jackman and Weisz give it all they've got, which is a lot, and Ellen Burstyn is always a welcome presence. Here she's the boss to Jackman's scientist, trying to keep him from flipping out when he discovers a cure at the very moment his wife dies. She doesn't succeed. There's a good deal of ponderous pronouncement like "Death is the road to awe" and a few nice special effects, as when the spaceman ingests the ooze from the Tree and begins to turn into a flowerbed. But the film as a whole is too unfocused to be either coherent or convincing.