|

| Bibi Andersson and Elliott Gould in The Touch |

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Friday, September 25, 2020

The Touch (Ingmar Bergman, 1971)

Wednesday, September 23, 2020

Here Is Your Life (Jan Troell, 1966)

|

| Eddie Axberg in Here Is Your Life |

Life doesn't have a plot. It's a series of incidents, some causally connected, some not. At least that's the life presented in Here Is Your Life, a coming-of-age story about a boy in Sweden during the years that comprised World War I. (Not that the war had much to do with it in neutral Sweden.) What we see is the emerging consciousness of Olof Persson (Eddie Axberg), a boy who, because his father is seriously ill, was sent to live with a foster family and when he is on the brink of turning 14, goes off to seek his fortune. That takes him first to dangerous places like a logging camp and a sawmill, then to work for a man who runs a movie theater, including a stint as an itinerant projectionist, carrying the camera from place to place. We also see him working on the railroad and trying to organize workers into a strike. Bright and highly literate, he gets his ideas from Nietzsche and Marx, and tries to apply them to the world he encounters. The film ends with Olof, now on the verge of manhood, striking out alone as the camera soars away from him, a tiny figure isolated on the railroad tracks running through a snowy landscape. It's a lovely, disjointed but somehow coherent movie, with enigmatic characters and violent events mixed with mundane but often striking ones. His sexual awakening occurs, too, though not without a bit of violence and confusion there: Once, his rough male coworkers indulge in a bit of horseplay with Olof that verges on rape. Later, he strikes up a friendship with a somewhat older man that has homoerotic overtones when the two swim naked and afterward dance together. The encounters with girls are more typical of the portrayal of growing sexual awareness in film: He falls for a pretty girl but rejects her when he sees her with someone else and a friend tells him she's promiscuous. He deflowers another young girl and leaves her in tears. And he has an affair with a very experienced older woman, marvelously played by Ulla Sjöblom. Yet Troell's film never sinks into clichés or banality, and it's held together by the director-cinematographer-editor's vision and by the steady, attractive performance of Axberg in the key role of Olof. There are also some appearances by such familiar Swedish actors as Allan Edwall, Ulf Palme, Gunnar Björnstrand, and, of course, Max von Sydow. The film's 168-minute length is a bit daunting -- it lost 45 minutes in its American release -- and Troell never spells things out for the viewer, leaving us to explicate the changes in Olof's life on our own. But the epic ambition involved in adapting a quartet of novels by Nobel laureate Eyvind Johnson somehow results in an intimate portrait of growing up.

Monday, September 21, 2020

Brink of Life (Ingmar Bergman, 1958)

|

| Ingrid Thulin and Bibi Andersson in Brink of Life |

For all the frankness of its subject matter, Ingmar Bergman's Brink of Life is as formulaic as a Hollywood movie of the 1950s. Three women are sharing a room in the obstetrics ward of a hospital. One of them, Cecilia (Ingrid Thulin), has miscarried and is being treated for bleeding. Another, Stina (Eva Dahlbeck), is in almost the opposite condition: She has gone well past term in her pregnancy and is there hoping that labor will be induced if it doesn't occur right away. The third, Hjördis (Bibi Andersson), is only in her third month, but she has experienced some bleeding -- perhaps, we learn, because she's unwed and doesn't want the baby, so she's been trying to cause a spontaneous abortion. Cecilia is in the throes of depression, blaming herself for the miscarriage because neither she nor her cold, priggish husband, Anders (Erland Josephson), was entirely certain that they wanted a child. Again, Stina is the precise opposite: She's rapturous about having a baby, and so is her husband, Harry (Max von Sydow). Between these polarities, Hjördis is fighting with the social worker who is trying to advise her on how she can live after the baby arrives. The best advice is, of course, to go home to her parents, but since she left precisely because she doesn't get along with her mother, she strongly rejects the idea of facing the disapproval she expects to encounter from her. It's all a setup for the kind of plot resolutions you might expect: Cecilia grows stronger and chooses to face up to her disintegrating marriage and a childless future. Stina loses the baby in a prolonged and difficult labor. And Hjördis discovers that maybe her mother isn't so bad after all. There's a feeling of anticlimax about these eventualities. That the film works at all is the product of the performances of the three actresses, along with Bergman's steadily unsentimental direction, which makes the predictability of the story more tolerable than it might be in a Hollywood tearjerker. Still, I can't help feeling that the stories of what happens to Cecilia, Stina, and Hjördis after the film ends would make a more interesting movie.

Thursday, August 13, 2020

Shutter Island (Martin Scorsese, 2010)

|

| Ben Kingsley, Mark Ruffalo, and Leonardo DiCaprio in Shutter Island |

Shutter Island is two hours and 18 minutes long, and it feels like it. North by Northwest (Alfred Hitchcock, 1959) is almost as long (two minutes shorter) and it doesn't. Yet Martin Scorsese, who made Shutter Island, is one of the few contemporary directors who are spoken of with much the same reverence as Hitchcock. Granted, comparing the two films is unfair: North by Northwest is meant to be giddy fun, constantly on the move, while Shutter Island is a psychological thriller with horror movie overtones and a claustrophobic setting. So perhaps the more appropriate comparison would be one of Hitchcock's explorations of disordered psychology, Psycho (1960) or Vertigo (1958). The former comes in at 109 minutes, the latter at just a few minutes over two hours. The point here is that Hitchcock knew how to tighten things up. Scorsese may know how, but he doesn't seem to care. He lets Shutter Island slop around, losing tension and focus in the process, when all he really has to do is guide us to a surprise twist and shocking climax. I seem to be one of the few who feel that the film is a tedious indulgence in material of no great matter: Its psychology is unconvincing, its characters are toys, and its payoff is rather pat and formulaic. Still, it gets a whopping 8.2 rating from viewers on IMdB, so I seem to be among the few who feel that too much acting and directing talent has been expended on too little.

Monday, December 16, 2019

Robin Hood (Ridley Scott, 2010)

Robin Hood (Ridley Scott, 2010)

Cast: Russell Crowe, Cate Blanchett, Max von Sydow, Oscar Isaac, William Hurt, Mark Strong, Danny Huston, Eileen Atkins, Mark Addy, Matthew Macfadyen, Kevin Durand, Scott Grimes, Alan Doyle, Douglas Hodge, Léa Seydoux. Screenplay: Brian Helgeland, Ethan Reiff, Cyrus Voris. Cinematography: John Mathieson. Production design: Arthur Max. Film editing: Pietro Scalia. Music: Marc Streitenfeld.

Did the world really need another Robin Hood movie? From the lack of interest at the box office, it would seem not. At least Ridley Scott and screenwriter Brian Helgeland tried to give us something slightly different: a prequel, in which Robin finds his identity and mission and only at the very end goes off into Sherwood Forest with his Merry Men, presumably to rob from the rich and give to the poor. We've had a sequel before in Richard Lester's 1976 Robin and Marian, in which the aging couple find an end to their adventures. (Interestingly, the Robin Hood of Lester's film, Sean Connery, was 46 when it was made, the same age that Russell Crowe was when he made Scott's. Lester's Marian, Audrey Hepburn, was 47, and Scott's, Cate Blanchett, was 41.) Unfortunately, the prequel doesn't give us much that's new or revealing about the characters: The villains, King John (Oscar Isaac) and the Sheriff of Nottingham (Matthew Macfadyen), remain the same, with an additional twist that they're being duped by another villain named Godfrey (Mark Strong), a supporter of the French King Philip, who is plotting an invasion now that the English army is still straggling back from the Crusades. Robin is a soldier of fortune named Robin Longstride, who has been to the Crusades and is making it back with the crown of the fallen Richard the Lionheart (Danny Huston) as well as a sword he promised the dying Sir Robert Loxley (Douglas Hodge) he would return to his father, Sir Walter (Max von Sydow) in Nottingham. When he does, Robin meets Marian, no longer a maid but the widow of Sir Robert. On the way, he has gathered a retinue comprising Little John (Kevin Durand), Will Scarlet (Scott Grimes), and Allan A'Dayle (Alan Doyle), and in Nottingham he will add Friar Tuck (Mark Addy) to the not terribly merry company. They'll take part in repelling the French invasion, which Scott makes into a kind of small scale D-Day, to the extent of borrowing unabashedly from Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan (1998), including some landing craft whose historical existence has been questioned (along with much else of the movie's history). Robin and his fellow soldiers, including Marian, who arrives disguised in chain mail, save the day, but their hopes for a new charter of rights that has been promised them by King John are dashed when he proclaims Robin an outlaw. So everything seems to be set up for a sequel that will culminate at Runnymede and the signing of Magna Carta, but the film's flop at the box office put paid to that. Robin Hood certainly has some good performances, which you might expect from its cast packed with Oscar-winners and -contenders, but it feels routine and a little tired. It also resorts to filming much of the action with the now too common "gloomycam," in which fight scenes always seem to be taking place at night, so you can't tell who's killing whom.

Tuesday, June 4, 2019

The Passion of Anna (Ingmar Bergman, 1969)

Wednesday, August 22, 2018

Miss Julie (Alf Sjöberg, 1951)

|

| Anita Björk, Märta Dorff, and Ulf Palme in Miss Julie |

Jean: Ulf Palme

Kristin: Märta Dorff

Countess Berta: Lissi Alandh

Count Carl: Anders Henrikson

Viola: Inga Gill

Robert: Åke Fridell

Julie's Fiancé: Kurt-Olof Sundström

Farmhand: Max von Sydow

Governess: Margarethe Krook

Doctor: Åke Claesson

Julie as a child: Inger Norberg

Jean as a child: Jan Hagerman

Director: Alf Sjöberg

Screenplay: Alf Sjöberg

Based on a play by August Strindberg

Cinematography: Göran Strindberg

Art direction: Bibi Lindström

Film editing: Lennart Wallén

Music: Dag Wirén

"Opening up" a play when it's made into a movie is standard practice. Directors don't want to get stuck in one or two sets for the entire film, so they shift some of a play's scenes to different locations or have new scenes written. But nobody has done it with such imagination and finesse as Alf Sjöberg, taking August Strindberg's Miss Julie out of the kitchen in which the play confines the characters and into the other rooms of the house and onto the grounds of the estate. Sjöberg plays fast and loose not only with space but also with time, giving us scenes from the childhood of some of the characters, showing us the cruelties that warped them into the twisted adults they have become. But he also does it by letting the characters from the past appear in the same room as their equivalents in the present, giving a sense of the indivisibility of past from present. Granted, Strindberg's play, with its long reminiscent speeches, facilitates this reworking of the drama by providing the material for Sjöberg's added scenes, but there's a fluidity to Sjöberg's melding of memories into the tormented present of Julie and Jean. There are some who argue that Miss Julie is meant to be a claustrophobic play, that dramatizing too much of Julie's relationship with her mother or Jean's early lessons in not transgressing the limits of class undermines the play's psychological realism with too much action and melodrama. The answer to this, I think, is that the play remains, and continues to be performed with success -- and, incidentally, to be filmed repeatedly in ways more faithful to Strindberg's original plan. What we have with Sjöberg's film based on Strindberg's play is a second creation, rather the way Verdi's Otello and Falstaff can stand on their own as masterpieces without denying the virtues of the Shakespeare plays on which they're based.

Thursday, January 25, 2018

The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973)

|

| Linda Blair, Max von Sydow, and Jason Miller in The Exorcist |

Father Damien Karras: Jason Miller

Regan McNeil: Linda Blair

Father Merrin: Max von Sydow

Lt. William Kinderman: Lee J. Cobb

Sharon: Kitty Winn

Burke Dennings: Jack MacGowran

Father Dyer: William O'Malley

Karl: Rudolf Schündler

Willi: Gina Petrushka

Karras's Mother: Vasiliki Maliaros

Demon's Voice: Mercedes McCambridge

Director: William Friedkin

Screenplay: William Peter Blatty

Based on a novel by William Peter Blatty

Cinematography: Owen Roizman

Production design: Bill Malley

Film editing: Norman Gay, Evan A. Lottman

Makeup: Dick Smith

From classic to claptrap, that's pretty much the range of critical opinion about The Exorcist. I tend toward the latter end of the spectrum, feeling that the novelty of the film has worn off over the 45 years of its existence, revealing a pretty threadbare and sometimes offensive premise. It was at the time a kind of breakthrough in the liberation from censorship that marked so much of American filmmaking in the early 1970s. Audiences gasped when Linda Blair growled "Your mother sucks cocks in hell" with Mercedes McCambridge's voice. Today it's little more than playground potty-mouth behavior. The pea soup-spewing and head spinning now draw laughs when they once had people fainting in the aisles. We can argue that there was something noble about those more innocent times, and that we've lost something valuable in an age when the president of the United States can brag about pussy-grabbing and denounce shithole countries and still retain the loyalty and admiration of a third of Americans. But isn't it also true that the move from a horror film based on religious superstition to a horror film like Jordan Peele's Get Out, nominated like The Exorcist for a best picture Oscar, represents an improvement in our taste in movies? Get Out at least has a keenly satiric take on something essential: our racial attitudes. The Exorcist makes no statement about the value of religious faith, unless it's to suggest that it's based on a desire to scare us into believing. To my eyes, The Exorcist is slick but ramshackle: William Peter Blatty's Oscar-winning screenplay never makes a clear connection between Regan's possession and Father Merrin's archaeological dig in Iraq. (The opening scenes of the film were actually shot in the environs of Mosul, which today has succumbed to a different kind of evil.) There are some scenes that make little sense: What's going on when the drunken film director taunts Chris's servant Karl with being a Nazi? What's the point of introducing the detective played by Lee J. Cobb with his usual self-absorption? Some of the plot devices, such as Father Karras's guilt over his mother's death, are pure cliché. And who the hell names a daughter Regan? Was Chris hoping for another kid she could name Goneril? For thousands of moviegoers, however, these objections are nitpicky. For me the flaws are the only thing that remain interesting about The Exorcist.

Wednesday, January 10, 2018

Winter Light (Ingmar Bergman, 1963)

Märta Lundberg: Ingrid Thulin

Karin Persson: Gunnel Lindblom

Jonas Persson: Max von Sydow

Algot Frövik: Allan Edwall

Fredrik Blom: Olof Thunberg

Director: Ingmar Bergman

Screenplay: Ingmar Bergman

Cinematography: Sven Nykvist

Production design: P.A. Lundgren

Film editing: Ulla Ryghe

I have to admit that I was seduced into nostalgia by the opening of Winter Light, as the liturgy and communion service brought back memories of my Methodist childhood. But the mood vanished swiftly as the chill reality of the film took hold: The church is cold and nearly empty, most of its congregants brought there by necessity or duty. The pastor is a hypocrite with a head cold, unable to muster enough enthusiasm for his faith to keep a man who comes to him for counseling from blowing his head off with a shotgun or even to console his widow. His former mistress, the local schoolteacher, is as comfortable in her atheism as he is uneasy in his attempts to believe. It's Bergman at his bleakest, though paradoxically filled with a kind of existential affirmation. The message boils down to: Don't sweat the big stuff. That is, don't let theology get in the way of going on with your life. You can respond to this kind of message in three ways: With stubborn denial, with an exhilarated sense of liberation, or with a painful feeling of loss. Winter Light is a talky film, one that sometimes seems more fit for the stage than for the movies, but its characters are alive and complex, its performances uniformly superb, and its images -- supplied by the great Sven Nykvist -- sometimes even more articulate than its dialogue.

Monday, October 9, 2017

Shame (Ingmar Bergman, 1968)

|

| Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow in Shame |

Jan Rosenberg: Max von Sydow

Jacobi: Gunnar Björnstrand

Mrs. Jacobi: Brigitta Valberg

Filip: Sigge Fürst

Lobelius: Hans Alfredson

Director: Ingmar Bergman

Screenplay: Ingmar Bergman

Cinematography: Sven Nykvist

Production design: P.A. Lundgren

Film editor: Ulla Ryghe

One of Ingmar Bergman's bleakest and best films, Shame is unencumbered by the theological agon that makes many of his films tiresome (not to say irrelevant) for some of us. It's a fable about a couple, Eva and Jan, two musicians seeking to escape from a devastating war by exiling themselves to an island. At the start of the film their life is almost idyllic: Their radio and telephone don't work, so they remain in blissful ignorance of the problems of the world outside. He's a bit scattered and idle; she's practical and businesslike. They quarrel a little over their temperamental differences, but they have developed a self-sustaining life, raising chickens and cultivating vegetables in their greenhouse. But needless to say, no couple is an island: The war comes to them. When they take the ferry into town, selling crates of berries and stopping to drink wine with a friend who has just been drafted, they begin to be aware that the larger conflict will not remain at a distance for long. There will be no retreat for them into the simple life. Under the pressure of war, their relationship changes: Eva becomes more careless, Jan loses his passivity. In the end, desperate to flee the despoiled island, they join a group on a fishing boat heading for the mainland only to wind up in a dead calm -- a literal one, for they are stuck in a sea filled with corpses, an image that, because so much of the film is straightforward in narrative and imagery, manages to avoid the heavy-handedness that often afflicts Bergman's films. There is also, for Bergman, a surprising lack of specificity about the war in the film: There are no direct allusions to particular wars, such as World War II, the one that raged in his childhood, or to the war of the day in Vietnam -- there are no images of burning monks as in Persona (1966). The war of the film is generic -- soldiers, planes, trucks, and tanks lack insignia and the names and nationalities of the two sides are never mentioned. It's as if war is an ongoing condition of the human race.

Monday, June 5, 2017

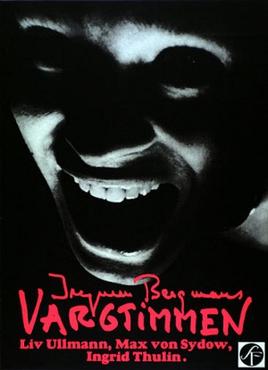

Hour of the Wolf (Ingmar Bergman, 1968)

Sunday, May 28, 2017

Europa (Lars von Trier, 1991)

|

| Jean-Marc Barr and Barbara Sukowa in Europa |

*Europa was released in the United States in 1992 under the title Zentropa to avoid confusion with Agnieszka Holland's Europa Europa, which had been released in 1991 in America. Von Trier also named his production company Zentropa, which is the name of the railway company in his film.