|

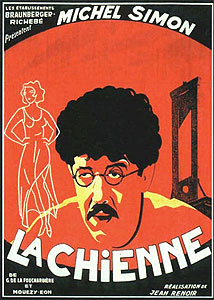

| Michel Simon and Germaine Reuver in La Poison |

I thought there was something off about the title of Sacha Guitry's La Poison, and I was right: The French word for substances like arsenic and strychnine is masculine -- le poison. When the word becomes feminine, la poison, it can be roughly translated as "pest" or "nuisance." Exploring the psychology behind the genders assigned to words in languages that have such inflections is dangerous, but it seems somehow in keeping with what some have called the film's "misogyny" that the feminine form of the word should take on such connotations. La Poison is a dark comedy about wife-killing, somewhat reminiscent of Charles Chaplin's Monsieur Verdoux (1947), though without Chaplin's sentimentality and tendency to moralize. The great Michel Simon, who is lionized in Guitry's extended opening credits sequence, plays Paul Braconnier, married to a slatternly drunkard, Blandine. She hates him as much as he does her, and is in fact the first to put in motion an attempt to do away with him when she buys a supply of rat poison. Eventually, however, he gets the upper hand (which holds a knife). But the film is most centrally about the justice system, in which sharp lawyers like the defense attorney Aubanel (Jean Debucourt) are able to help the guilty escape the guillotine. Braconnier hears Aubanel on the radio, talking about how he has just achieved his hundredth acquittal, so Braconnier goes to see him, pretending that he has just murdered his wife, when in fact he's really there to figure out the safest way to do it. Shrewdly, Braconnier tricks the attorney into pointing him in the direction of the best ways to murder someone -- by, for example, staging it to look like self-defense and to avoid any hints of premeditation. So Braconnier goes back to his village and does Blandine in, then recruits Aubanel for the defense. The lawyer is indignant at being so used, but Braconnier has the goods on him as an unwitting accomplice in the crime. He stands trial and is acquitted. Guitry has learned a lot about filmmaking since his movies of the 1930s, which were often more static and talky than was good for them, and there's a crispness and fluidity to La Poison that's admirable. Simon is at his best in the trial scene, but there's a sourness to the concept that keeps the film from being entirely enjoyable. Critics and scholars of Guitry's work have pointed out that it's a bit of revenge flick, its hits at the judicial system expressive of Guitry's resentment at having been interned as a collaborator after World War II, when in fact he was always anti-Nazi and even helped some Jewish friends escape.