|

| Franco Citti in Accattone |

Vittorio "Accattone" Cataldi: Franco Citti

Stella: Franca Pasut

Maddalena: Silvana Corsini

Ascenza: Paola Guidi

Amore: Adriana Asti

Director: Pier Paolo Pasolini

Screenplay: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Sergio Citti

Cinematography: Tonino Delli Colli

Film editing: Nino Baragli

There are times in Pasolini's first feature when he seems to be trying out things that he will accomplish with greater finesse in his later films. For example, there are several walk-and-talk tracking shots in which Accattone and another person walk down a street toward a receding camera. This technique was used with greater force and wit in Pasolini's next film,

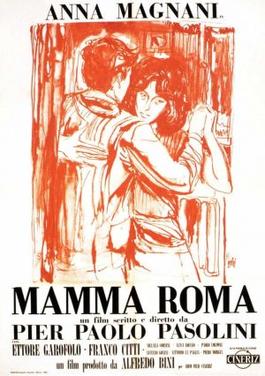

Mamma Roma (1962), in which Anna Magnani strides down a nighttime street, talking about her life, as various people emerge from the darkness to deliver comments on what she is telling us. We've seen this sort of thing done many times since the development of the Steadicam -- it has become a kind of cliché in films and TV shows written by Aaron Sorkin -- but even though the shadow of the retreating camera rig occasionally creeps into the frame in

Accattone, Pasolini and cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli execute it with considerable skill. Skill is not always in evidence in

Accattone, which has its rough, raw edges. It's not always easy to follow Pasolini's screenplay, drawn in part from his early novels, when it comes to the relationships between the various characters: I'm not clear, for example, who the young woman with several small children is who shares a room with Maddalena and later Stella. Pasolini had worked with Federico Fellini on

Nights of Cabiria (1957) and it's instructive to compare the two films: Fellini's has greater technical finish, but it's also less harsh and more sentimental, which may be why Fellini, who originally planned to produce Pasolini's film, withdrew his support. But the rawness of

Accattone is entirely appropriate for a film that evokes the spontaneity and actuality of early Italian Neo-Realism with its non-professional actors and ungroomed settings. And it has at its center a charismatic performance by Citti, an untrained actor who went on to a long career on-screen that included an appearance as Calo, one of Michael Corleone's Sicilian bodyguards in

The Godfather (Frances Ford Coppola, 1972). "Accattone" is a nickname that means "beggar" or "ne'er-do-well" or "layabout" -- the character's given name is Vittorio Cataldi -- and is entirely appropriate for a character who begins as a pimp and, after hitting the skids and even trying work (at which he shudders), winds up as a thief -- a dead thief. Citti's voice was dubbed in the film, but most of the work is done by his extraordinarily expressive face and by a physical commitment to the role. There is, for example, a terrific fight scene between Accattone and the men of his ex-wife's family, which ends with Accattone and his opponent locked together in a struggle in the dirt, neither willing to relinquish hold. Pasolini also emphasizes the dissonance between a world that produces an Accattone and the religious background from which it springs by using excerpts from Bach's St. Matthew Passion on the soundtrack.

.jpg)