A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Wednesday, December 21, 2016

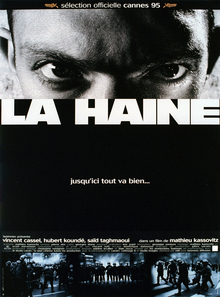

La Haine (Mathieu Kassovitz, 1995)

Would the friendship of the Jew, Vinz (Vincent Cassel), the African, Hubert (Hubert Koundé), and the Arab, Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui) be possible in the Parisian banlieus today? For that matter, was it in fact possible when writer-director Mathieu Kassovitz made La Haine in 1995? Or was it a symbolic construct to emphasize solidarity against the Establishment and the corrupt police force, somewhat like the ethnic stews of Italian-, Irish-, and Jewish-Americans (but never, sadly, African-Americans) that Hollywood filmmakers put on bomber crews and destroyers during World War II as a way of promoting solidarity against the enemy powers? The question is rhetorical, of course, and not designed to undermine the importance and brilliance of Kassovitz's terrific (and terrifying) film, made in response to outbreaks of violent protest in the poorer suburbs of Paris. It has the quality of some of the best neo-realist Italian films of the postwar years, with the additional sense of something about to erupt that pervades the film and has not dissipated in the 21 years since it was made. If anything, it has spread into the rest of the world, especially in the post-9/11 era. The trio of actors on whom the film mainly focuses is extraordinary, both individually and as an ensemble.