|

| Nancy Kelly and Patty McCormack in The Bad Seed |

Cast: Nancy Kelly, Patty McCormack, Evelyn Varden, Eileen Heckart, William Hopper, Henry Jones, Paul Fix, Joan Croydon, Gage Clarke, Jesse White, Frank Cady. Screenplay: John Lee Mahin, based on a play by Maxwell Anderson and a novel by William March. Cinematography: Harold Rosson. Art direction: John Beckman. Film editing: Warren Low. Music: Alex North.

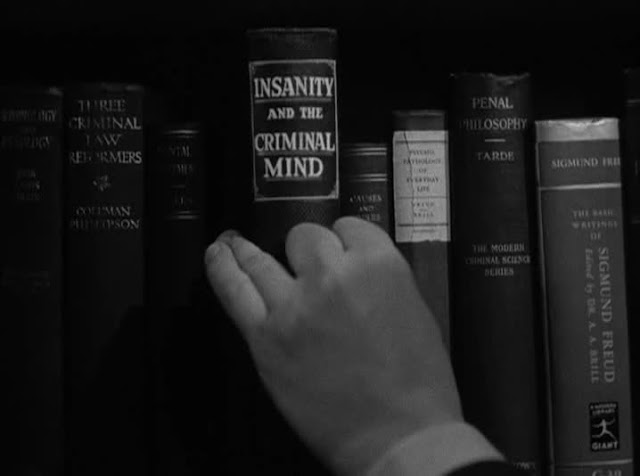

The Bad Seed stands out today as one of the more muddle-headed products of Production Code censorship. In the play and novel on which the movie was based, Christine Penmark, the unwitting carrier of the gene that turns her daughter, Rhoda, into a serial killer, commits suicide after giving the child an overdose of sleeping pills. One of the shocks of the novel and play is that Rhoda survives to kill again. But suicide as a positive plot resolution and crimes that go unpunished were taboo under the Code, so John Lee Mahin's adaptation blunts the ending for both characters. And then, to add farce to bathos, someone thought it a good idea to add a "curtain call" sequence in which the actress playing Christine, Nancy Kelly, gives the actress playing Rhoda, Patty McCormack, a spanking. Since spanking is hardly a punishment for murder, you have to wonder if Kelly is punishing McCormack for upstaging her. (In any case, McCormack seems to be enjoying it a little too much.) Still, if you take the movie on its own terms, it has its creepy moments, most of them involving McCormack, whom we spot as a bad kid from the moment she shows up with her braids so tight it looks like they hurt and wearing a starchy, spotless outfit that no decent child would have tolerated for a moment. There's some entertaining overplaying by Evelyn Varden as the psychologizing landlady and Henry Jones as the nosy hired man. The production is stagy and the performances often overblown, with the exception of Kelly, who strives to make her character -- and the ridiculous premise that evil is inherited -- credible. It's a role that could easily have tipped over into camp -- as the rest of the film often does -- but Kelly balances right on the edge.