|

| Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney in Where the Sidewalk Ends |

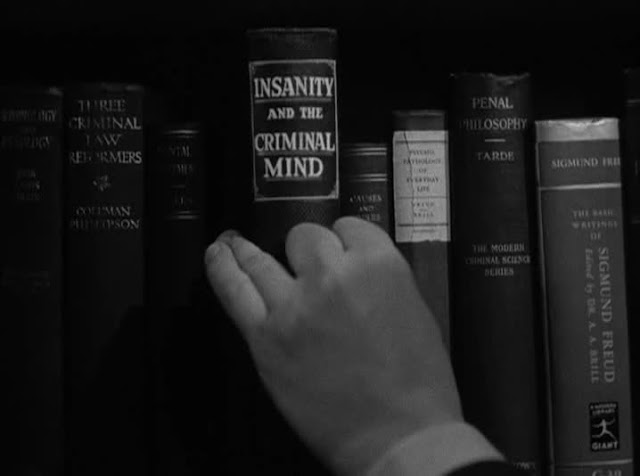

In Where the Sidewalk Ends, Dana Andrews plays Mark Dixon, a tough cop who's just a little too eager to rough up the suspects, and he starts the film by getting demoted for it That barely fazes him, however: When he's called on to interview Ken Paine (Craig Stevens), a suspect in a murder that's just been committed, Paine fights back and Dixon punches him out. Unfortunately, Paine had a severe head injury in the war, and he dies. Dixon's attempts to cover up only make things worse, leading to a snarl of consequences that form the plot of this darkly entertaining crime drama. What elevates Where the Sidewalk Ends into more than routine is mostly Ben Hecht's richly slangy, cynical dialogue and Otto Preminger's smooth direction. It helps, too, that Preminger is working with people who made his Laura (1944) one of the classics of Hollywood film: Andrews, of course, who even shares the name Mark with his cop counterpart in Laura, Gene Tierney as another leading lady with a lousy taste in men, and cinematographer Joseph LaShelle, who won an Oscar for the earlier movie. Laura was, however, almost baroque in contrast with the tight, spare Where the Sidewalk Ends, which depends on Hecht's skill at crafting tough talk to overcome some of the story's reliance on pop psychology: Dixon, it seems, developed his sadistic approach to police work because he hated his father, who was a hoodlum gunned down by the cops. The film ends on a nicely unresolved note after Dixon admits to killing Paine and trying to cover it up at the same time that he's being honored for bringing mobster Tommy Scalise (Gary Merrill) to justice.