|

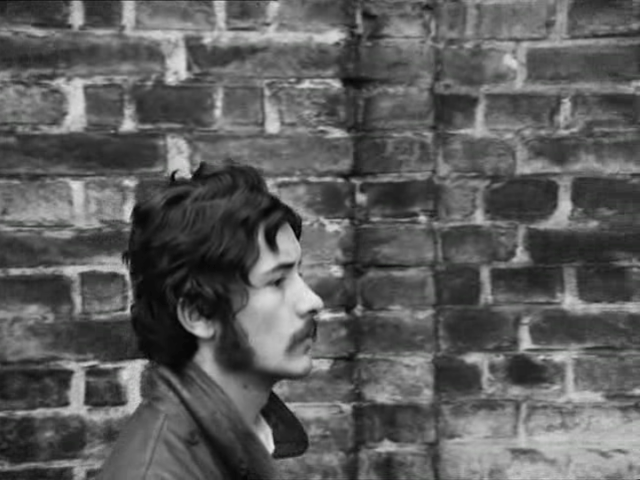

| Sigourney Weaver, Harry Dean Stanton, Yaphet Kotto, John Hurt, Tom Skerritt, Veronica Cartwright, and Ian Holm in Alien |

Dallas: Tom Skerritt

Lambert: Veronica Cartwright

Brett: Harry Dean Stanton

Kane: John Hurt

Ash: Ian Holm

Parker: Yaphet Kotto

Director: Ridley Scott

Screenplay: Dan O'Bannon, Ronald Shusett

Cinematography: Derek Van Lint

Production design: Michael Seymour

Music: Jerry Goldsmith

Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) posited that extraterrestrial beings might not be bent on world domination or worse, but instead were just looking to be friendly neighbors. Spielberg went on to reinforce that idea in 1982 with E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. It was a kind of reversal of the treatment of space creatures in 1950s sci-fi films, born of Cold War paranoia. But although the Spielbergian vision informed several other successful films, including John Carpenter's Starman (1984), the truth is that when it comes to movies, paranoia is fun. No movie established that more clearly than Alien, whose huge success launched a whole new era of shockers from outer space, including Carpenter's The Thing (1982). Almost 40 years later, Alien still holds up, while the Spielberg films are looking a bit sappy. Is that a commentary on the movies themselves, or on us? Alien benefits from near-perfect casting and from outstandingly creepy design, making the most of the work of H.R. Giger on the alien and its environment and of Carlo Rambaldi (who had also created the benign aliens of Close Encounters and E.T.) on animating the creature. While it's true that time has not been entirely kind to some parts of the design -- such as the cathode ray tube monitors for the ship's computers, which would definitely be outmoded in 2037 when the film is set -- everything else has become sci-fi standard, including the depiction of the Nostromo as an aging tub of a ship whose maintenance crew, Brett and Parker, gripe about being paid less than the management staff. Scott doesn't labor over the implicit critique of corporate capitalism that will become more prominent in the sequels, but it's nice to see it there.