|

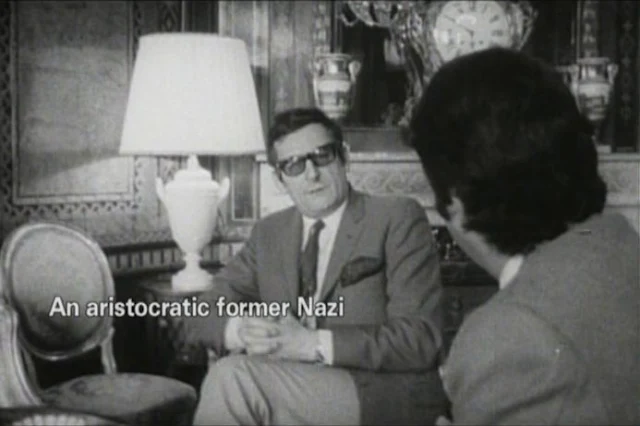

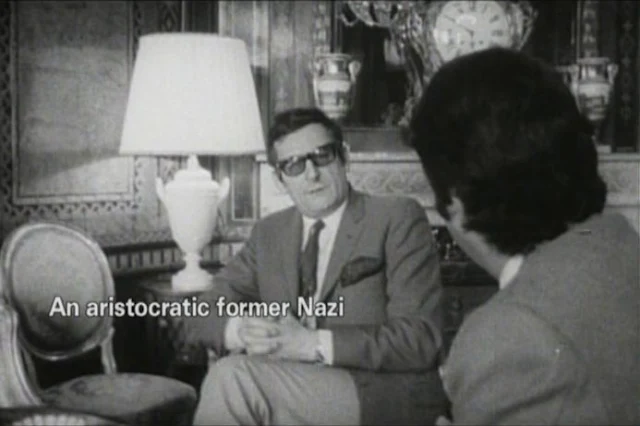

| Christian de la Mazière, one of those interviewed in The Sorrow and the Pity |

An adverse political situation typically elicits three responses: collaboration, resistance, and patient endurance. The problem with the third is that it's hard to sustain under pressure from the other two. Such is the lesson of

The Sorrow and the Pity, the great documentary by Marcel Ophüls about France during the German occupation. It can't be said that Ophüls is even-handed and impartial in his treatment of the survivors of that era who testify in his film. That kind of disinterestedness is not only impossible but immoral, considering the horrors inflicted by the Nazis. But it's the kind of film that makes you understand what people endured, and question how you yourself would have behaved in the same (or a similar) situation. That's also why I think the film is essential viewing, especially this week, with the inauguration of a man whose thoughts and actions seem so abhorrent to many people and so attractive to others.