A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Monday, December 29, 2008

That's a Load off My Mind

My sight, I know, has improved slightly. Now it's almost like there's less of a blind spot than a sort of wrinkle in what my left eye sees. I told my daughter, as she was driving me back from the appointment, that I'm almost ready to try driving -- around the block. Neighbors beware!

Oh, and I got a haircut, my first in maybe five or six months. I had it shorn back to the No. 2 buzz cut that I had before. The only fault is that it makes the hole in my head -- a depression in the scalp about the size of a dime -- more visible. But he jests at scars who never felt a wound, right?

Friday, December 26, 2008

Climbing the Phone Tree

It was a mistake fairly easily corrected. Medicare had me listed as having "other insurance" as the primary payer. It seems that Medicare updates its records once a year, in October. So unless you make a point of telling them what's going on, if you change insurers after their update day, they won't know about it until next October. In my case, I had paid-up insurance from my former employer through the end of October 2007 -- after the Medicare update. At the end of October, that policy ceased, and Medicare became my primary carrier. (I also have a Medicare supplemental policy.) But Medicare didn't know about it, so all of my medical bills from October 2007 to October 2008 were denied.

This good news out of all this medical mishegoss is that it was relatively easily cleared up. Conservatives are always arguing against government programs because of the "bureaucracy." But my experience with Medicare is that their bureaucracy is more efficient and responsive and more pleasant to deal with than that of the big private insurance companies. Maybe it's because the big private insurance companies can pick and choose whom they insure, while Medicare has to deal with anyone over 65, some of whom must require careful and clear explanations. As I know from my experience in the nursing home, anyone who works with the elderly needs the patience of a saint.

This is, of course, another argument for a single-payer national insurance system -- the only kind of health reform that I think will work. It took me three phone calls to clear it all up -- one to the clinic to find out why the charges weren't paid, one to Medicare to ask why they weren't listed as the primary insurer and to be assured that the mistake was corrected, and another to the clinic to ask them to resubmit. One phone call should have been sufficient.

And don't get me started on voice-recognition phone trees:

ROBOVOICE: You said "enrollment."

ME: No, I didn't! I said "claims."

ROBOVOICE: Please choose from one of the following options....

Thursday, December 25, 2008

We Wish You a Murray Crispness

Walla Walla, Wash., and Kalamazoo.

Nora's freezing on the trolley.

Swaller dollar cauliflower alley-ga-roo.

Don't we know archaic barrel?

Lullaby lilla-boy, Louisville Lou.

Trolley Molly don't love Harold.

Boola boola Pensacoola hullabaloo!

Wednesday, December 24, 2008

A Heartbreaker

Sunday, December 21, 2008

Product Placement

I learned this tip from a nurse at the Ambulatory Treatment Infusion Center (acronymically called, of course, "the attic") when I was describing how hard it was to wrap a plastic bag around my left arm with my right hand in order to cover my PICC line. They had given me one of those plastic sleeve thingies that are usually used to cover casts, but it also covered my left hand, meaning I couldn't use it to wash with.

So I got a roll of Press'n Seal (why they can't call it, more correctly, "Press 'n' Seal" I don't know) and sure enough, it does the trick.

What a strange little world of expediencies I have found myself in.

Friday, December 19, 2008

...Or Maybe Rachel Maddow Is the Smartest Person on TV

Visit msnbc.com for Breaking News, World News, and News about the Economy

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

An Eye for an Eye

Oddly enough, her candor appeals to me. I'm a little tired of the choruses of "Climb Every Mountain," "You'll Never Walk Alone" and "Cockeyed Optimist" that people keep singing at me. A little honest resignation to reality never hurt anyone.

Sunday, December 14, 2008

Nothing But the Tooth

All these questions occurred to me as I was lying on a bed in the hallway at the Stanford E.R., waiting for the diagnosis of what had made me go partially blind. (Literally in the hallway. Stanford's E.R. is so crowded that it has put beds in the hall, especially for patients who don't need modesty curtains. They're even labeled: Hall 1, Hall 2, etc.) My neighboring patients included a woman with no family, no job (hence, no insurance), and a variety of serious and unpleasant illnesses; a diabetic man who had neglected the injury to his foot he received on the job and was now threatened with amputation because it had turned gangrenous; and a grizzled biker type who was there because he wanted a pain-killer for -- he said -- a really bad toothache. The young resident who saw him winced at the state of the man's teeth.

"How long has it been since you saw a dentist?"

"I dunno. A while I guess."

"You need to see one."

(with utter lack of conviction) "OK."

He got the meds and left.

We're constantly told how important dental health is. How infected teeth can spread infection to the rest of the body. In my case, in which the source of an infection was crucial, I was repeatedly quizzed about my teeth. (I am pleased to report that there was a chorus of admiration when a team of doctors and med students examined my "dentition" one day. I must tell my fine young dentist, Dr. W., to whom I once commented, "I have fillings older than you." He has since replaced them. Expensively.)

So why isn't dentistry an integral part of the medical picture? I guess if I Googled enough I'd get an answer, something to do with the histories of the separate professions, rivalries and jealousies and economic advantages. But in a time of reform, when everything is being examined with a view to making it new, when "holistic" is a byword, shouldn't this odd, arbitrary division between dentistry and medicine be re-examined?

Thursday, December 11, 2008

What You See Is What You Get

What amazes me is how a simple, everyday task could have become so arduous. Because even though I could see the shoes perfectly clearly -- i.e., no cloudiness or blurring or double vision -- I couldn't see the difference between them. I would have to feel for the arch inside -- and even then, I sometimes failed to match the shoe to the correct foot.

My problem, it seems, was one of pattern recognition -- something that the brain does to help us see. I could "see" the shoes, but I didn't "get" them, if you know what I mean.

The first time I recognized this phenomenon was when I was in the hospital. Lying in bed, unable to read or make sense of what I saw on TV, my mind wandered everywhere, but especially to my home. And I realized to my horror that I couldn't visualize it. I even tried to map out a floor plan in my head, but it was as if my imagination couldn't hold anything as complex as a rectangle.

When I first arrived at the nursing facility, one of the therapists had me play the kids' game Connect Four -- the one in which you drop checkers into slots so they line up. Get four in a row -- vertically, horizontally, or diagonally -- and you've won. But I couldn't make sense of the game. I especially couldn't see the diagonal pattern. It was revelatory, but also depressing.

The first thing I mastered was the clock on the wall. I could see the hands perfectly clearly, but I couldn't make them tell time for me. Gradually, however, the ability returned. And the first time I saw a calendar I was baffled. I had "forgotten" the familiar pattern of the calendar -- left to right, starting with Sunday. I would scan across to Saturday and then have no idea which way to go, until I "remembered" that I had to look at the leftmost date on the next line. On the other hand, things that involved some kind of muscle memory rather than visual techniques, such as tying my shoes, never went away.

I still have a gap in my vision. I notice it most when I'm reading, a process that involves scanning lines from left to right. When your eye reaches the end of one line, it darts back to the left-hand margin and begins the next. But sometimes, when I'm reading particularly wide text, as on some Web sites, the gap in my vision puts in a fake "margin" to which my eye goes. I have to force my eye beyond this imaginary margin to the real one.

The thing is, through all these experiences, I remained perfectly lucid and verbal -- or at least I think I did. Which only made them more frightening. The brain is a scary organ.

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Abscess Makes the Heart Grow Fonder

After three months away, things have changed around the house. That is, nothing is where I left it. Which for a mild (?) obsessive-compulsive like me is disturbing. Nevertheless, after my first outpatient IV session today, I vow to come home and rest.

Sunday, December 7, 2008

Second Childhood

Still, it bothers me to hear a 90-year-old man say things like "I need to go potty" or "I have to wee-wee." And the nursing staff encourages it. Instead of "urinate" and "defecate," they say "pee-pee" and "poop" or even something I hadn't heard since third grade: "No. 1" and "No. 2." (No one uses the most familiar four-letter Anglo-Saxonisms.)

At first I thought this was an example of the infantilization that some critics decry in our culture. But then I lightened up. These twee euphemisms are the ones that almost every parent uses so often during the toilet-training years that it shouldn't be surprising when they become second-nature to us.

But something in me still thinks that being sick -- or just very, very old, as most of my roommates have been -- should be treated with frankness, not cutesiness.

Saturday, December 6, 2008

More on TB

And I may have to modify my previous assertion that I don't have TB. When I said that to Dr. B. yesterday, he said not to be so sure. My history of respiratory problems could have its source in the bacillus. Well, damn. And as Kristof's column says, there's not a lot of new research on TB, partly because it's a disease of the poor, who don't tend to fund research. So I am scrupulously gulping my antibiotics -- literally bitter pills.

Where the Heart Is

The following review was written for the Houston Chronicle and e-mailed to them shortly before I got sick. Somehow the e-mail went astray, and the review never ran because I was incommunicado when the editor tried to get in touch with me about it. Sad, because it was one of my favorite books of the year.

The following review was written for the Houston Chronicle and e-mailed to them shortly before I got sick. Somehow the e-mail went astray, and the review never ran because I was incommunicado when the editor tried to get in touch with me about it. Sad, because it was one of my favorite books of the year. HOME

By Marilynne Robinson

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 336 pp., $25

Home is the place where, when you have to go there,

They have to take you in.

Everything that Frost packed into that wry aphorism – need, obligation, exploitation, resistance, resentment – Marilynne Robinson unpacks in her magisterial, breath-stealing new novel, “Home.” Everything and more, for Robinson also ventures into such difficult topics as love and faith.

These are difficult topics for fiction not only because they can betray writers into sentimentality, but also because so much of the drama of fiction depends on hatred and doubt. As Milton discovered, Satan inevitably gets all the best lines. Yet the drama in Robinson’s novel consists of the struggle of good people to love and believe in one another and at least to make the attempt to believe in God.

Glory Boughton has come home to Gilead, Iowa, to look after her father, Robert, an elderly Presbyterian minister in his last days. Before long, word comes that her brother Jack will be joining them. Neither Glory nor her father has seen Jack for 20 years, since he left Gilead in disrepute; he even failed to return for his mother’s funeral.

Glory is the novel’s central consciousness – the third-person narration sticks to her point of view – and she has secrets of her own that she’s hesitant to share with her father and her brother. But during the weeks of his visit in the summer of 1956, she will share her secrets with Jack in order to learn some of his own. The novel is a delicate dance of guilt and forgiveness, involving not only the three Boughtons but also Robert’s old friend and fellow minister, John Ames, for whom Jack was named.

Readers of Robinson’s 2004 novel “Gilead,” which won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle award, will know these characters already. But they won’t know them the way they’re presented in “Home,” which tells essentially the same story about the homecoming of Jack Boughton, but tells it in a new and surprising way. “Gilead” was John Ames’ journal, a testament written for his small son, a profoundly meditative novel. “Home” is meditative, but it’s also a more theatrical novel.

Not “theatrical” in the pejorative sense (that is, florid and overstated) but in the sense that, as in a play, much of the tension and substance of the novel lies in the things the characters say to one another. It’s a novel that takes place on a stage of sorts: the Boughton home, its rooms cluttered with “unreadable books” and furniture in “sour, fierce, dreary black walnut” with “leonine legs and belligerently clawed feet.” The porch is “overgrown by an immense bramble of trumpet vines,” and there is an “empty barn,” “useless woodshed,” “unpruned orchard and horseless pasture.” This is the place that has taken Glory in, a 38-year-old unmarried woman who must by the end of the novel decide whether to let the past – home -- define her for the rest of her life.

But before that, she has to deal with Jack and their father, and with John Ames, who disapproves not only of Jack but also of his father’s willingness to overlook Jack’s transgressions. The novel moves through a series of crises, some of them provoked by Ames’ words and some by Jack’s tendency to adopt an ironic self-distancing that slicks over his underlying desire to be accepted and forgiven. As Glory moves among these characters, she comes to recognize and embrace her kinship with Jack, even though she is ostensibly the most dutiful of the eight Boughton children and he the most prodigal of the sons and daughters.

A moment of almost telepathic recognition of this kinship comes in mid-novel when Jack makes a remark that annoys Glory:

“That was a little flippant, she thought. She went into the kitchen to peel potatoes for a salad.

“After a while he came into the porch and the kitchen and stood by the door.

“ ‘I’m sorry,’ he said.

“ ‘What for?’

“ ‘When we were talking just now. I think I may have seemed – flippant.’

“ ‘No. Not at all.’

“ ‘That’s good,’ he said. ‘I didn’t mean to. I can never be sure.’ Then he went outside again.”

That’s an utterly simple yet impeccably crafted account of the way a casual word or expression or action can ripple seismically through the consciousness of others. And it’s characteristic of Robinson, who has a sensibility attuned to “the intimacy of the ordinary,” to rip one of her own phrases out of its context. She is a writer of rare grace, whose words seem to fall into place as naturally and freshly as raindrops.

Don’t worry if you haven’t read “Gilead,” to which this novel is both companion and complement. You can begin with “Home” and then read the other. But you may be tempted when you finish “Home” just to start over and read it again. It’s that good.

Friday, December 5, 2008

Liberation Day

Thursday, December 4, 2008

Groundhog Day

A devout friend writes that he has me in his prayers. This old agnostic is almost willing to believe that they're working.

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

Tuesday, December 2, 2008

TB or Not TB

In the age of prosperity and antibiotics, tuberculosis is a disease of people who live in cardboard boxes under bridges. (At least in countries without, ahem, a national health insurance program.) But as anyone who knows Romantic poets, Victorian novels or grand opera is aware, it used to be more widespread.

My mother had tuberculosis when I was 3 or 4. She spent a year in a sanitarium and had part of a lung removed, yet she lived to be 75. (She might have lived longer -- her sister lived till she was 90 -- if she hadn't given in to depression and essentially starved herself to death, refusing to eat. Which is why I'm no foe of antidepressants.) Moreover, her father, who lived with us until I was 8 or 9, also had TB. So whenever I have to fill out one of those medical history questionnaires the doctor give you, I mention this exposure.

TB is not all that contagious, I think. None of my mother's six siblings contracted it, nor did my father. But I've had a history of upper-respiratory crud -- from sinusitis to pneumonia (twice) to an empyema, so doctors are quick to send me to X-ray.

Which is good, except that this time they decided that TB was a prime suspect, even though the usual pinprick skin test was negative, and they sent me to lock-up: a private room in the contagious ward, accessed by a kind of airlock and only by people wearing face masks. I spent three days there producing sputum samples -- coughing (even though I didn't have much to cough) into a little plastic cup full of weird-smelling chemicals.

I don't have TB, and I suppose I should be grateful for their thoroughness in making sure of the fact. But for a time there I wondered if instead of being Bette Davis in Dark Victory -- alerted to the onset of death from a brain tumor by losing her eyesight -- I was going to be Greta Garbo in Camille. Fortunately, I'm neither.

Sunday, November 30, 2008

What's in a Name?

"Is your name Arsenic?"

"Ar-say-nich," she said softly, a little wearily, as if answering the question was a burden she had borne for a long time. She was Croatian, she said, and the "c" was pronounced "ch."

Even so, it's an unsettling name for a nurse. You couldn't get away with a Nurse Arsenic in fiction. It would be like calling a surgeon Jack Ripper.

The word "arsenic," I learn from Wikipedia, is from the Greek, meaning "masculine" or "potent," which is how, I suspect, it became a Croatian surname. The Greeks got the word from the Persian, where it meant "yellow orpiment" -- a pigment. (Artists used to get arsenic poisoning from their paints.)

I suspect that Miss Arsenic, if she stays in the United States, will change her name, just as countless Vietnamese named Phuc have decided to do.

I don't mention all of this to make fun. No doubt there's a language somewhere in which "Matthews" means "foreskin" or monkey dung."

Saturday, November 29, 2008

It's All in My Head

But on the other hand, just a few weeks ago I thought I'd never be able to read again. When I woke up that morning and the clock said 26 and Julian Barnes had become Ian Barnes, it wasn't that there was a blot or a blur in front of the 7 or the Jul-. It was as if my brain was telling me they weren't there. Later, lying on a gurney in a hallway at Stanford Hospital, I would watch people going by in a hall that crossed the one I was in. They would walk in from the right and then at a certain point simply vanish, as in some cheesy movie special effect. And other people would appear from the left out of sheer nothingness.

My brain was simply incapable of processing some of the information it was receiving. But it was doing the best it could. I think Julian became Ian because my brain knew Ian was a proper name. But Barnes didn't become Nes, because it knew that to be a nonsensical name.

Things got worse over the next few days, which I spent in a very nice private room in the ground floor isolation ward while they made sure I didn't have tuberculosis (another story for another day). It had a big window opening onto an enclosed garden. But I couldn't make sense of what was outside, couldn't distinguish trees from walls, shrubs from flowers; it was a mass of green with dots of colors that I toook to be blossoms. Later, I moved to a third-floor ward in which occasionally you could hear the hum of an engine starting up. It was the Medevac helicopter, which landed on the roof nearby. Visitors told me that from my window they could see the chopper taking off. But I never brought it into view. Maybe my brain thought it wasn't worth seeing.

As for reading, I developed a kind of dyslexia: Words refused to shape themselves into coherent syllables. Letters swapped places. The name "MERYL" was written on a dry-erase board on the wall -- presumably the name of a supervising nurse, not the actress. But my brain kept rearranging and substituting the letters. "Meryl" became "Merlyn" became "Merry." Was it simply trying out variations to see what worked?

Nor was watching TV any better. Profoundly bored, I wound up listening to a classical music station when I wasn't sleeping. But classical music on the radio is "easy listening" for office workers: classical Muzak. After several days of Baroque jangle I gave up. I don't care if I never hear Vivaldi again.

Finally, a few days after I left the hospital for the rehab facility, an occupational therapist put a book in front of me and asked me to try to read it. Maybe several weeks of ennui had persuaded my brain that this was a good thing to do, because the words took shape and stayed in place.

They say that when one part of the brain is injured, the other parts try to compensate, to work around the crippled part, to form new neural pathways or something. I believe it now. I haven't regained my sight completely. Occasionally someone will speak to me on my left and I'll have to search for the speaker. I look at cartoons on the Internet and don't get the joke -- the new pathway in my brain hasn't developed a sense of humor, perhaps.

Most embarrassing, I seem to have lost the easy automatic approach to familiar tasks: I put my shoes on the wrong feet. I have to be careful pulling a polo shirt over my head lest it go on inside-out or wrong-side front. I've been known to make several attempts at this before succeeding. Yet there are tasks -- like tying my shoelaces -- that are as automatic as they've been since I learned them many decades ago.

Some day, a long while from now, maybe I'll try driving. But I can't think about that now.

Friday, November 28, 2008

List, List, O List!

This review appeared recently in the Washington Post Book World:

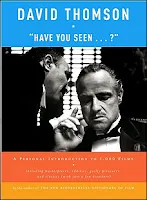

“HAVE YOU SEEN...?”

A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films

By David Thomson

Knopf, 1024 pp., $39.95

Everybody loves a list. The American Film Institute, for example, gets a couple of TV specials every year out of listing the 100 best movies in some genre or other. And every film critic in the country is annually obligated to come up with a list of the top ten movies of the year.

But a list of 1,000 films? The vastness of such a project betrays its absurdity: No one's critical sensibility is so fine-tuned as to allow a convincing distinction in quality between the thousandth film on the list and the dismissed thousand-and-first.

David Thomson is the author of numerous film books – biographies, histories, essays, even novels – all marked by passion, curiosity, scholarship and wit. His Biographical Dictionary of Film, with its blend of factual information and critical insight, is one of the essential movie books, and “Have You Seen...?” was proposed by his editors as a kind of companion volume. Thomson says in the introduction that he designed it to answer the question he's asked frequently: “What should I see?” But really, the book is an excuse for Thomson to wander around the gargantuan buffet table of movies, gleefully picking and choosing, sampling, savoring (and sometimes spitting out) whatever catches his fancy. He also makes it clear from the beginning that he's not going to be tied down by any list-making principle other than that there have to be 1,000 entries of approximately 500 words each. The first entry – the book is arranged alphabetically -- is Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, which he says is there because a friend told him he couldn't lead off the book with any film so solemn and earnest as the one he first chose: Abe Lincoln in Illinois. High seriousness is not Thomson's typical mode, so to set the right tone for the book, Bud and Lou replaced Abe and Mary.

Blithely making up the rules for inclusion as he goes along, he slips in entire TV series (“Monty Python's Flying Circus,” “The Sopranos”) when it suits him and when he can make a point (e.g., “The Sopranos” shows how much better the Godfather films are). There were to be no documentaries until he decided to include one because it was made by Orson Welles (F for Fake). And he even includes a film that he hasn't seen for more than 30 years and hasn't been able to find a print of: Roger Vadim's Sait-On Jamais..., which Thomson admits is “not a great movie,” but remembers for its great jazz soundtrack. The entry leaves you wondering about the thousand-and-first movie that got dropped so one he saw nearly half his lifetime ago could be included.

To put it succinctly, “Have You Seen...?” is a big, glorious, infuriating and illuminating mess. You'll be happiest with it if you're on Thomson's wave length, that is, if your favorite directors include Renoir, Hawks, Welles, Hitchcock, Preston Sturges, Ozu, Mizoguchi, Antonioni, Bergman. You'll be less happy if you prefer Ford, Wilder, David Lean, Woody Allen, Scorsese, Kubrick, Kurosawa or Fellini, all of whom he finds wanting in one way or another. He acknowledges what he regards as their best work, but even then his preferences can be startling. He thinks, for example, that Otto Preminger's Exodus is better than Lean's Lawrence of Arabia. His favorite Allen film is Radio Days, which he calls “a masterpiece.” Annie Hall, on the other hand, he regards as “disastrously empty.” Taxi Driver, he says, “is a great film ... hallucinatory, beautiful and scarring.” Whereas the movie a lot of people think of as Scorsese's masterpiece, Raging Bull, he finds “fascinating, but truly confused.” You don't come to such books just to sate your complacent taste, but to bristle at the things you disagree with and to whet your counter-arguments.

But with a universe of films to choose from, it's sad that Thomson wastes space and energy getting in a few more kicks at a movie like The Sound of Music, which has been stomped on by every reputable critic for the past 43 years and still keeps cheerfully toddling along, chirping about raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens. It's the Teflon musical, and Thomson's treatment of it is more like bullying than criticism. He says he includes it because “millions of the stupid and aggrieved will write in to the publisher, 'Where was The Sound of Music?'” But so what if they do? This belies the advice he had given only a few entries earlier, writing about why he includes Vincente Minnelli's Some Came Running instead instead of his Gigi: “If you love Colette, Gigi is ghastly. If you don't love Colette, put this book aside.”

In the end, everyone who doesn't put it aside will find much to like and learn from. Thomson is, after all, an incisive observer and a tremendously clever writer, and his enthusiasms have taken him into dusty corners: He's a great fan of film noir, for example, so the book is dotted with obscure melodramas from the 1940s. There are also films in the volume that only a few fanatics like Thomson have even heard of, let alone seen. But everyone will also find something missing. For example, he stints on the great genre of animation, including only a few Disney classics, an odd little essay on the Tom and Jerry short “The Cat Concerto,” and a nice tribute to Sylvain Chomet's The Triplettes of Belleville, in which he disses the Pixar films because he finds their “sunniness ... boring and complacent.” That's his prerogative, but why no acknowledgment of the work of Chuck Jones and others at Warner Bros.? Or the miraculous films, like Spirited Away and Princess Mononoke, of Hayao Miyazaki?

See, that's the thing about lists. Give us a thousand films to think about, and we'll still think about the ones you left out.

Thursday, November 27, 2008

My Own Private 9/11

My first thought was: Stroke. My second was: Tumor.

Many hours and several CTs and MRIs later, I learned that I had a brain abscess, an infection that had left me with limited peripheral vision in my left eye. As it turns out, the stroke or the tumor might have been more manageable.

"How do you get an infection in your brain?" my daughter asked.

I didn't know. I'd never heard of such a thing. But typically, the infection spreads there from somewhere else. Once they figure out where, and can identify the culpable bacteria, they can deal with it.

The trouble is, almost three months later, the culprit remains at large. I've had a brain biopsy (I needed another hole in my head). And they've run tests on every part of me, with no success. "The Mystery Man!" a neurologist recently greeted me when I went for a checkup. I can't share his enthusiasm for becoming a medical anomaly.

Still, the antibiotics they've been flooding me with -- intravenously as well as orally -- seem to be helping. At my last checkup, about a month ago, the lesions had begun to shrink -- or so the MRI suggested.

(Ever had an MRI? It's like lying in a sewer pipe on which someone is banging with a ball peen hammer, and next to which someone is using a jackhammer and occasionally blowing an air horn next to your ear.)

Anyway, this is all to explain to anyone who might have tuned in to this blog to read about books why I haven't been much in evidence lately. I spent the month of September in Stanford Hospital. Since then, I've been in a skilled nursing facility -- largely because Medicare pays for most of it. (The anomalies of the American health care system -- if "system" is the right word for it -- are something I've experienced firsthand. It's possible that I'll be here for six months longer.)

The thing is, I'm feeling great. I've recovered much of my sight -- or at least have learned how to overcome the deficiency -- and I've been working out with physical and occupational therapists every day. I'm in better physical shape (aside from the pus in my brain) than I've been in years.

But I can't go home. I'm tethered to an IV pump that feeds antibiotics into my system via a PICC line. PICC is "Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter," but nobody calls it that because nobody can pronounce "peripherally." Mine runs from my left biceps through my veins to my heart. Every eight hours, I get a new bag of antibiotics, and a nurse shoots a syringe of saline through the PICC to flush it.

Too much information?

Anyway, I'm back. I'm taking a break from reviewing for obvious reasons. But a couple of reviews of mine have been published since I got sick, and I'll post them soon.

Stay healthy!

Sunday, August 31, 2008

Learning to Read

HOW FICTION WORKS

By James Wood

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 266 pp., $24

"How Fiction Works" is an audacious title, not only because explaining the mechanisms of fiction is a large task but also because fiction doesn't seem to be working as well as it used to, if you take the decline in book sales as evidence. But if any contemporary critic is up to the task, it's James Wood, who has read more and better than the rest of us. Wood, who reviews for the New Yorker, has also published a novel, "The Book Against God," so he knows first-hand about the making of fiction.

"How Fiction Works" is an audacious title, not only because explaining the mechanisms of fiction is a large task but also because fiction doesn't seem to be working as well as it used to, if you take the decline in book sales as evidence. But if any contemporary critic is up to the task, it's James Wood, who has read more and better than the rest of us. Wood, who reviews for the New Yorker, has also published a novel, "The Book Against God," so he knows first-hand about the making of fiction.This is anything but a densely theoretical book. Wood doesn't waste time on defining the term "fiction." He assumes that we know it when we see it. Instead, what he gives us is a demonstration of smart reading, an exploration of works of fiction by a sensibility finely attuned to both the words on the page and the tricks an author plays in an effort to make it real.

"Making it real" is what the book is about; as he tells us at the outset, "the real … is at the bottom of my inquiries." Fiction, he says, "floats a rival reality." It "does not ask us to believe things (in a philosophical sense) but to imagine them (in an artistic sense)."

To this end, he discusses the usual elements of fiction -- point of view, description, style, characterization, dialogue. The only thing he doesn't spend much time talking about is plot -- he even refers to "the mindlessness of suspense" and "the essential juvenility of plot." Plot matters for him only as an outgrowth of the characters -- the dilemmas they face, the decisions they make, the lessons they learn, the flaws that undo them.

Most of the burden of his argument is focused on "free indirect style" -- what some of us usually refer to as limited third-person narrative. For Wood, it most effectively exploits the essential tension of fiction, the relationship of author and character: "Thanks to free indirect style, we see things through the character's eyes and language but also through the author's eyes and language. We inhabit omniscience and partiality at once."

He dazzles us by citing examples of free indirect style not only from its master, Gustave Flaubert, but also from Robert McCloskey's children's book, "Make Way for Ducklings." And he shows us how violating point of view and voice can be fatal to the narrative balance between character and author with a devastating example from John Updike's novel "Terrorist," in which Updike, writing from the character's point of view, inserts a detail with significance for the author but one that would probably not occur to the character. The passage in Updike’s book, he tells us, "is an example of aestheticism (the author gets in the way) ... which is at bottom the strenuous display of style."

Eventually, Wood gets around to E.M. Forster's famous distinction in "Aspects of the Novel" between "flat" and "round" characters. He comments that "Forster is genially snobbish about flat characters, and wants to demote them, reserving the highest category for rounder, or fuller characters." But Wood finds that "the very idea of 'roundness' in characterization ... tyrannizes us -- readers, novelists, critics -- with an impossible ideal," and in a footnote (some of the best stuff in Wood's book is in the footnotes) tentatively proposes a distinction between transparent characters and opaque ones. The opaque ones are characters like Hamlet and Iago, whose motivation retains a certain mystery.

Of course, Wood is largely concerned with what we sometimes call "literary" fiction -- as distinguished from "popular" or "commercial" fiction. In constantly striving to make it new, to dodge clichés, literary fiction leaves behind a clutter of old conventions that linger in popular fiction. "Commercial realism has cornered the market, has become the most powerful brand in fiction,” Wood says. “The efficiency of the thriller genre takes just what it needs from the much less efficient Flaubert or Isherwood, and throws away what made those writers truly alive." Even the best commercial fiction, Wood posits, citing a passage from John le Carré's "Smiley's People," "is a clever coffin of dead conventions."

But the chief joy of Wood's book is its abundance of shrewd close readings of such writers as Austen, Flaubert, James, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Kafka, Woolf, Nabokov, Bellow, Roth and Updike -- among many others. (The bibliography at the book’s end is a deliciously enticing reading list, if you’re looking for one.) He helps us understand how they achieve (and sometimes fail to achieve) what he calls "lifeness: life on the page, life brought to different life by the highest artistry."

"How Fiction Works" is, in essence, a master class in reading.

Sunday, August 10, 2008

Summer Page-Turners (and Some Aren't)

By Andrew Davidson

Doubleday, 480 pp., $25.95

“The Gargoyle” is a tricked-out romance about a man who was severely burned when his car went off a cliff and a woman who sculpts grotesque statues and may be schizophrenic. But wait, there more. Before he was disfigured, the man was a devastatingly handsome porn star and a coke-head. And the woman claims that she’s 700 years old and that she and the man were lovers back in the 14th century, when she was a nun and he was a mercenary soldier. You don’t get hookups like that on Match.com.

By now you may have decided whether this novel sounds like it’s for you, and you’re probably right. If you’re interested in spending almost 500 pages deciding if he was and if she isn’t, then “The Gargoyle” will keep you happily turning pages for several summer days. And if you aren’t, then you’ve been warned.

This is the first novel by Andrew Davidson, a Canadian writer in his 30s who says in an interview supplied with the review copy, “I have a list of things that I want to do before I die: become a published novelist was on that list. The list remains long.” He also reveals that at successive stages in his earlier life, he “wrote a great many mediocre” poems, plays and screenplays.

“The Gargoyle” isn’t mediocre, thanks to Davidson’s solid research into the effects and the treatment of burns. The first part of the novel contains harrowingly convincing descriptions of what the novel’s anonymous narrator underwent during the accident and his recovery. They give the novel a grounding in reality that it seriously needs.

Davidson also knows how to tell a story, how to withhold and reveal details at the right time. As the narrator recovers, the woman – who calls herself Marianne Engel, her surname being the German word for “angel” -- tells him engaging old tales of true love, and gradually unfolds the story of the relationship she claims they had in their earlier life together.

But Davidson also has the novice fiction writer’s inability to self-edit, to toss out both the needlessly clever and the tiresomely familiar. As the narrator grows more and more dependent on morphine to help him through recovery, he imagines that his spine has been replaced by a demonic serpent: “The sibilant sermons of the snake as she discoursed upon the disposition of my sinner’s soul seemed ceaseless,” he writes, summoning up a silly, self-conscious hiss. At other times, even such dubious cleverness eludes him, as when the narrator tells us at a moment of crisis that “Desperate times call for desperate measures,” reminding us that weary writers resort to dried-up catchphrases.

And in the end, the narrator and Marianne never become much more than puppets in Davidson’s pageant of Love and Redemption. They are sometimes provocatively imagined, but they’re not such fully living characters that we put much emotional stock into what direction their relationship takes. They’re only ideas, and not terribly original ones at that.

The Gargoyle reminded me of another much-hyped debut novel of a few years ago, which I reviewed at the time for the Mercury News:

THE HISTORIAN

By Elizabeth Kostova

Back Bay, 642 pp.

If you've never read ''Dracula,'' that great, clumsy novel by Bram Stoker, you really should go do it. And don't think because you've seen any number of film versions of the story that you've really gotten at its creepy essence.

The vampire legend reaches back to antiquity, but because it's really about our fear of and fascination with sex, it seems to crop up most in times of repression or anxiety. That may be why it got its definitive treatment from Stoker at the end of the Victorian era. And why the age of AIDS has seen a charnel-houseful of cold-blooded but hot vampires. Think of Lestat and his cohorts in Anne Rice's novels, and the broody dudes Angel and Spike and the femmes très fatales Darla and Drusilla on ''Buffy the Vampire Slayer.''

''Buffy'' put a feminist spin on the vampire story, which in Stoker's hands had been about imperiled virgins and their doughty male defenders. And now Elizabeth Kostova gives us another intrepid heroine, less hip than Buffy but no less determined to stake her claim as an eradicator of evil.

Kostova's heroine, who remains unnamed throughout the book, is a historian at

When Paul showed the book to one of his professors, Bartholomew Rossi, he learned that Rossi possessed a similar book, and had tried to trace its origins. What Rossi learned convinced him that ''Dracula -- Vlad Tepes -- is still alive.'' A few days after telling Paul this, Rossi disappeared, leaving traces of blood in his office.

So Paul began a quest to find out what happened to Rossi, which led him to an encounter with a woman named Helen Rossi, who claimed to be the professor's unacknowledged daughter. And she joined forces with Paul in the search for Rossi.

The narrator is fascinated, not least because her mother, whom she never knew, was named Helen: ''I did not dare repeat the name aloud . . . she was a topic my father never discussed.'' But before she can hear the rest of her father's story, she awakes one morning to find a note from him: He's been ''called away on some new business,'' and he wants her to wear a crucifix and carry garlic in her pockets.

No self-respecting heroine is going to leave it at that, of course. And so we get three related stories all mixed up together: the narrator's search for her father, his search for Rossi, and Rossi's own quest for the truth about the undead Vlad Tepes. And these stories, set in three different eras (the '30s, the '50s and the '70s), take us to

And will you care enough to keep reading for more than 600 pages?

Sure you will. Vampire stories are irresistible, and Kostova has stuffed hers with arcane history and colorful locales. There are plenty of narrative cliffs from which the story is hung, and an abundance of creepy or dubious characters. (My favorite is the ''evil librarian'' -- an epithet that made me laugh every time I encountered it.) ''The Historian'' is the kind of book you won't put down -- but you may not be glad you picked it up.

Kostova not only resuscitates Stoker's villain -- apparently all that business about Van Helsing and company putting a dusty end to Count Dracula was just fiction -- but also evokes Stoker's way of telling a story. ''Dracula'' is an epistolary novel -- or, more precisely, a documentary novel, since it's told not only through letters but also through entries in the characters' journals and diaries. Kostova's heroine is the central narrator, but this is a book of stories nested within stories, flashbacks within flashbacks, so a lot of it is told through the journals and letters she uncovers.

''Dracula'' zips along so breathlessly that you don't trouble yourself with the awkwardness of the documentary narrative, the story's inconsistencies and improbabilities, and the fact that Stoker is nobody's idea of a prose stylist. ''The Historian,'' on the other hand, feels overextended, and there are so many digressions -- stories within stories within stories -- that the pacing goes slack, giving you time to wonder, for example, how her characters can recollect, in precise detail, events and conversations that took place years earlier. And when you ask that, the illusion goes poof.

''The Historian'' is Kostova's first novel, and it's said to have taken her 10 years to research and write. Too bad she didn't take a little more time and work out some of the kinks in her prose. She slips too often into cliches: ''Chills crawled on the back of my neck.'' And there's way too much dialogue in which the exposition seems to have gotten stuck in the characters' throats, like this: ''It seems to me too much of a coincidence that you appeared when we had just arrived in Istanbul, looking for the archive you have been so much interested in all these years.''

But worst of all, Kostova forgets what made ''Dracula'' such a grabber. It's the Count who counts, and Stoker -- with the help of actors from Max Schreck to Bela Lugosi to Gary Oldman -- made him the stuff of our nightmares. Kostova often seems more interested in giving us lore about the historical Dracula and in touring

Monday, August 4, 2008

Bird's Blythe Spirit

By Sarah Bird

Knopf, 302 pp., $23.95

Sarah Bird’s new novel is a Cinderella story. Although when it begins, her Cinderella has already married and divorced the Prince; she’s been booted from the palace not by her wicked stepmother but by her wicked mother-in-law. She has to return to the scullery, but she finds there the equivalent of a fairy godmother. And when another Prince comes along, she has some helpers, like the mice and birds of the Disney version, to prep her for the ball.

But in truth, Bird’s heroine, Blythe Young, is an anti-Cinderella. Her “trailer-trash tramp of a mother” had christened her Chanterelle – “in her single, solitary moment of maternal lyricism she had named her only child after a mushroom.” After graduating from the

Now, trying to make a comeback as a caterer after her divorce, she stages a garden party for one of her old socialite friends. But when the hostess discovers that Blythe is passing off taquitos from Sam’s Club as Petites Tournedos Béarnaise à la Mexicaine, she threatens to withhold payment. Whereupon Blythe spikes the party’s kir royales with Rohypnol.

Blythe has been fueling herself with her “proprietary blend of Red Bull, Stoli, Ativan, just the tiniest smidge of OxyContin, and one thirty-milligram, timed-released spansule of Dexedrine.” She’s up, she’s down, and – having slipped a mickey to the cream of

Blythe’s antithesis, altruistic Millie tends not only to the needs of Seneca House’s fringe-dwelling college students but also to various street people: homeless men, illegal-immigrant day workers, and panhandling runaway teens. With Blythe’s arrival, this secular saint meets the devil wearing Prada. (Actually, Blythe is decked out in her last remaining outfit, Zac Posen with Christian Louboutin shoes.)

And thus Blythe plummets – ascends? – from Bushworld into hippiedom, giving Bird a chance to gleefully skewer the denizens of both planes of Austin existence and serve them up as a satiric shish kabob. Readers of Bird’s novels know that she loves her misfits, and won’t be surprised that in the end, hippiedom wins out. Not to give anything away that the reader won’t see coming a mile off, this time it’s the fairy godmother who gets her prince while anti-Cinderella learns a few things about what really matters.

How Perfect Is That doesn’t have the range and depth of Bird’s best novel, The Yokota Officers Club, or the engaging exploration of a subculture found in her most recent one, The Flamenco Academy. It has to be said that her satiric target, the Bush-worshipping nouveaux riches, is as bloated as a blimp, and that Bird attacks it with a broadsword. The women all have names like Kippie Lee, Bamsie, Cookie, Blitz and Missy, and they vie with one another to see who can build the most extravagant mega-mansion in

Topical satires usually wind up in the remainder bins, victims of creeping obsolescence. But How Perfect Is That takes note of the winds of change. The story begins in April 2003, a month before the declaration of “Mission Accomplished,” when Bush’s popularity was near its post-9/11 peak. But time wounds all heels, and by the end of the novel, even Kippie Lee and Bamsie are distancing themselves from the president: “We never really liked Bush anyway,” Bamsie confesses to Blythe. “Every Southern girl in the country knew a hundred frat guys just like Bush and every one of them was smarter and better looking.”

Bird’s snark is tempered with heart, and the tug of her plotting and the warmth of her characterization overcome the occasional heavy-handedness of the satire. Blythe is a splendid creation, a kind of Auntie Mame for the Internet age. Though How Perfect Is That isn’t perfect, it’s exactly what you’re looking for if you want an enjoyable summer read.

As I noted, How Perfect Is That isn't quite up to the standards of either The Yokota Officers' Club or her more recent The Flamenco Academy. Here's my review of the latter:

By Sarah Bird

Knopf, 381 pp., $25

Early in her career, Sarah Bird wrote a clutch of romance novels as Tory Cates – a pseudonym that might be translated as "conservative delicacies," which almost sums up the damsels-and-rakes genre in a phrase. But genre fiction is too limiting for a writer as irrepressibly clever as Bird, whose novels under her own name have earned her critical praise and a small, enthusiastic following. The best of them is probably "The Yokota Officers Club," a coming-of-age tale about the rebellious daughter of an American military family stationed in

In her latest, "The Flamenco Academy," Bird has given us another coming-of-age story, but her central plot is one that Tory Cates might have dreamed up: A shy virgin meets a dark, handsome, mysterious man who awakens in her the possibilities of passion, but when he disappears from her life as suddenly as he entered it, she becomes obsessed with finding and winning him. Her quest will take her into the heart of the exotic culture from which he emerged.

There are passages of the ripest romance in "The Flamenco Academy," but they blend into Bird's funny, touching portrait of two misfit girls, Cyndi Rae Hrncir and Didi Steinberg. They meet as high school seniors in an

Didi has a hunger for stardom that she feeds by playing groupie to touring bands. One night, Rae follows her to a post-concert party at a motel, and meets a flamenco guitarist who has hitched a ride with the band. Rae is captivated by his music – and by him, especially after he helps her escape when the party is raided by the police. The two of them spend the evening wandering the city, but when he discovers she's a virgin he abruptly backs off, flags down a ride and disappears from her life.

Through an Internet search, Rae identifies the mystery man as Tomás

Didi follows Rae to the first flamenco class and gets caught up in the dance. Soon the two are star pupils, but with very different styles. Doña Carlota dubs Didi "La Tempesta" because of her fiery but undisciplined style. Rae has a better understanding of compás, the complex rhythms of flamenco, because she can translate them into mathematical patterns. Doña Carlota calls her "La Metrónoma," for her technically perfect, metronomic mastery of compás. She tells Rae and Didi, "'The head and the heart. Together you are the perfect dancer. Apart?' She gave an

What chance could these two misfits have at excelling in flamenco, an art whose greatest practitioners are Gitano por cuatro costaos – "Gypsy on all four sides"? Didi (née Rachel) Steinberg, "the little girl who wanted AC/DC to play at her bat mitzvah," was born to a Filipina mother and a Jewish father. And Rae has to acknowledge that she's "the exact reverse of all things flamenco, … my broad, pale Czech face … evidence that, not terribly far back in my genetic lineup, there were generations of dozy, strawberry blond milkmaids, all pale as steam."

But Didi reinvents herself. She becomes a star, the diva Ofelia, by studying "Doña Carlota in the same omnivorous way she watched Madonna and

"The

But good conflict makes good fiction, and that's what gives "The Flamenco Academy" such irresistible energy and narrative drive. And what really makes the novel more than just an exceptional summer read is Bird's wonderful ability to create a milieu, from the Albuquerque prowled by teenage girls to the Spanish caves inhabited by Gypsies. Best of all, she gives us the complex lore and intricacies of flamenco, which Didi – always one to get the last word -- describes as "obsessive-compulsive disorder set to a great beat."

Sunday, July 20, 2008

The Plot Thickens

PALACE COUNCIL

By Stephen L. Carter

Knopf, 514 pp., $26.95

Advice to novelists: Never make the protagonist of your novel a novelist, unless you can be sure that the reader would rather be reading your novel than the ones your character has written.

The protagonist of Stephen L. Carter's third novel, Palace Council, is a novelist who by the end of the story has won at least two National Book Awards and is one of the most famous writers in America. Carter is pretty famous himself. He's the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law at Yale and the author of seven very serious nonfiction books about religion, morality and the law, though he's better known for his bestselling thrillers, The Emperor of Ocean Park and New England White.

The milieu of Carter's novels is the one inhabited by the upscale professionals -- lawyers, professors and the like -- and the haute bourgeoisie of "the darker nation," a phrase Carter uses for African-Americans. In Palace Council, it turns out that the phrase was coined by the novel's protagonist, Edward Trotter Wesley Jr.

In 1954, Eddie Wesley comes to Harlem to work as a journalist after graduating from Amherst and spending a couple of years in graduate work at Brown; his father is a Boston clergyman and his mother has family connections with the Harlem elite. Before long he has fallen in love with the beautiful Aurelia Treene, but she decides to marry the prince of Harlem society, Kevin Garland. Eddie leaves their engagement party despondently and, while cutting through a neighborhood park, he stumbles over the body of a white man, Philmont Castle, a prominent Wall Street lawyer who had also been a guest at the party.

Palace Council has a lot in common with Carter's earlier novels: The Emperor of Ocean Park centered on the Garland family, and New England White began with the accidental discovery of a body. And in all three books the protagonist is plunged into the middle of a mystery not of his or her making. But where the mysteries in Carter's earlier books unraveled over the course of months, it takes Eddie more than 20 years to figure out what the murder of Philmont Castle has to do with almost everything else that happens to and around him.

By the time the novel ends, the United States has gone through the turmoil of the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War and the protest against it, Watergate and Nixon's resignation. Eddie's sister, Junie, has disappeared into the revolutionary underground of the 1960s; he has been investigated by J. Edgar Hoover's FBI and written speeches for John F. Kennedy; he has been kidnapped and tortured while reporting in Saigon; he has befriended Richard Nixon. And he has foiled a secret plot to seize control of the U.S. government.

What is original in all of Carter's novels is his focus on the "darker nation," on the role played by African-Americans in recent American history, and on the way the unique social institutions that the black upper class constructed in the age of segregation were changed by the fractures in racial barriers. In a year that has seen the emergence of the first truly viable African-American presidential candidate, that ought to be a rich theme for a writer to exploit.

But Palace Council keeps getting hung up on the intricacies of its rather improbable plot, which deals with a conspiracy based on, of all things, Milton's Paradise Lost. Between the thriller plot and the love story -- Eddie's infatuation with Aurelia continues through the book -- the several interesting things that Carter has to say keep getting lost.

The book does demonstrate that Carter is capable of clever writing. He gives us, for example, an aspiring Democratic presidential candidate named Lanning Frost who seems to be an amiable dunce manipulated by an intensely ambitious wife. Frost's public utterances are couched in a kind of Bushian bafflegab. For example, when asked about the student protests on campuses, "Lanning nodded importantly. 'Well, naturally, none of us really want our once-proud universities run by the kind of situation where anybody reaches the level of controversy we need to attain,' he announced.

"The crowd cheered."

But Carter is no satirist. Palace Council is a curiously toneless book, as if Carter the law professor were unwilling to let Carter the novelist betray a strong feeling or attitude toward anything. This is a novel in which J. Edgar Hoover, John and Robert Kennedy, and Richard Nixon appear, and are all treated with a bland even-handedness and given dialogue that barely characterizes them at all. (Nixon, in fact, speaks in choppy sentence fragments that sound like the elder George Bush.) At its worst, the novel sinks to cliché, as when Eddie meets a shadowy, implacable hired killer who greets him with a line that was tired when Ernst Stavro Blofeld first purred it to James Bond: "I think it's time we had a little talk."

Eddie Wesley becomes a successful novelist by writing books like Field's Unified Theory, about an African-American physicist's quest for the goal that eluded Einstein; Blandishment, the coming-of-age story of a black student at a New England college; and Netherwhite, about a social climber rejected by the black upperclasses. Is it inappropriate to say that all of these sound more interesting than yet another political-conspiracy thriller with an overcomplicated plot?

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

Sunday, July 6, 2008

The Stripper and the Terrorist

The following review appeared today in the Houston Chronicle:

The following review appeared today in the Houston Chronicle: By Andre Dubus III

Norton, 537 pp., $24.95

Novelists keep being drawn to the events of September 11, 2001, hoping to confine the heinous imponderables of that day into the shapings of fiction. Writers as various as Jay McInerney (The Good Life), Jonathan Safran Foer (Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close) and John Updike (Terrorist) have made their attempts at it.

It’s hardly surprising that Andre Dubus III should join them with his new novel, The Garden of Last Days. Even before 9/11, in his 1999 novel House of Sand and Fog, he gave us a story that reverberated with the larger conflicts between America and the Middle East. It was a deftly constructed novel about the conflict between a somewhat feckless single woman and an exiled Iranian colonel. Oprah selected it for her book club and made it a bestseller.

Nine years later, Dubus has written another novel about a single woman, April Connors, who works as a stripper at the Puma Club for Men in Sarasota, Fla. She has a three-year-old daughter, Franny, whom she usually leaves with her landlady, Jean, while she works. When Jean gets ill, April is forced to take Franny to the club and let her watch Disney videos in the manager’s office before she falls asleep. But while April is entertaining a customer in one of the club’s private rooms, Franny wakes up and goes in search of her mother.

Franny is discovered at the back door of the club by AJ Carey, a construction worker who was kicked out earlier for getting too familiar with one of the strippers. His wrist was broken in the fracas and now, full of booze and painkillers, he has come back for revenge. What happens next is not good, and it messes up several people’s already messed-up lives.

So how does 9/11 come into all this? When Dubus read news reports that some of the hijackers had visited strip clubs and hired prostitutes in the days and weeks before their final flight, he thought about writing a short story about the encounter of a terrorist and a stripper.

It might have made a potent short story, but instead this encounter is wedged into a 500-page novel where it bears only a thematic relationship to the central plot. The Garden of Last Days takes place in early September 2001, and the customer April is entertaining in the Champagne Room of the Puma Club is a young Saudi named Bassam who, a few days later, will be one of the hijackers. (Dubus has fictionalized the terrorists’ names.) In a few lines of dialogue between Bassam and April, Dubus economically sums up one of the novel’s central themes:

“ ‘I should not like you, April.’

“ ‘Why shouldn’t you?’

“He lit another cigarette, inhaled deeply. ‘Because then I would be like you. And I am not like you.’ ”

Bassam, the terrorist, can’t fulfill his mission if he drops his habit of objectifying the enemy, if he treats non-believers like April as human beings and not as targets. The operative irony here is that April herself works in a milieu in which women are objectified -- treated as sex objects and not as human beings. But the problem is that Bassam has only a thematic role in the novel. He doesn’t fit into the plot; he affects neither its origins nor its outcome. And he doesn’t fit stylistically.

Dubus tells his story in discrete segments, each narrated from a point of view limited to one of the characters: April, Bassam, AJ, Jean and a bouncer at the club named Lonnie. He has richly imagined the way each of his American characters lives and thinks. But his imagination lets him down in the portrayal of Bassam.

Dubus roots Bassam’s fanaticism in some pretty thin psychology: a mixture of Oedipus complex (his last act before leaving to board the plane is to mail a letter to his mother) and sibling rivalry with his Westernized older brother Khalid, who died when he crashed his American car. Dubus lards Bassam’s narrative with Arabic words and quotes from the Qur’an, and he resorts to stiff, archaic syntax to emphasize Bassam’s foreignness: “So often he has asked himself why do these kufar have so much power?”

The result is that Bassam’s sections of the novel feel stagy and mechanical, whereas the emotional responses and moral dilemmas faced by April, AJ and Jean are real and touching. We learn of April’s ability to separate herself as Franny’s mother from the persona she adopts when she works in the club, and of her guilt and rage when Franny’s disappearance breaks down her tendency to compartmentalize. We enter into AJ’s confusion and desperation after he makes the impulsive decision to drive away from the club with Franny in his truck. And we experience Jean’s loneliness, her possessiveness toward Franny, the child she never had, and her distaste for April’s way of life.

Dubus’ novel makes a solid impact with its searching examination of its characters’ blind self-centeredness. But it would have that impact even if Bassam’s story had never been inserted into it. For his final act on Sept. 11 has no direct effect on the lives of the other characters. In fact, where the novel is concerned, only one of the characters, the bouncer Lonnie, is even indirectly affected by what happened on 9/11. The Garden of Last Days would have been a stronger, more coherent novel if Bassam had been omitted from it.