The following review appeared today in the San Francisco Chronicle:

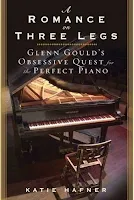

The following review appeared today in the San Francisco Chronicle:A ROMANCE ON THREE LEGS:

Glenn Gould’s Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Piano

By Katie Hafner

Bloomsbury

Concert pianists are notoriously temperamental, but with good reason: so are their pianos. Why else would J.S. Bach specify a “well-tempered clavier”? The modern piano is a jury-rigged contraption consisting of a multitude of tiny moving parts and a lot of steel and wood that has to be twisted, warped and tortured into just the right shape and structure. And it needs constant tuning, twiddling and tweaking to maintain the sound the pianist wants. No wonder that Glenn Gould, who twisted, warped and tortured himself into a great pianist, had such a love-hate relationship with the instrument that he referred to as an “intriguing mixture of pedals, pins, and paradox.”

It’s ironic that the pianoforte, as the instrument had been named because it could play both soft and loud, is now known as a piano: Virtuosi from Liszt to Lang Lang have mostly exploited the forte. But Gould wanted a piano that would sound, as he put it, “a little like an emasculated harpsichord.” He detested the Romantics, and once said his favorite composer was the 16th-century Englishman Orlando Gibbons. After a long search he found the cleanness of tone and quickness of action he wanted in a Steinway concert grand with the designation CD 318.

Katie Hafner is eloquent about why Gould loved CD 318 so much – so eloquent that one wishes her book included a discography of the recordings he made on that instrument. (His two most famous recordings – the versions of Bach’s “Goldberg Variations” he recorded in 1955 and 1981 – were made on other pianos.) “A Romance on Three Legs” is partly a biography of Gould, partly a history of Steinway & Sons, and partly a story about how technique, tastes and technology propelled the evolution of the piano. It’s also a tribute to piano tuner Verne Edquist, whose exquisite sensitivity and technical inventiveness manipulated CD 318 into an instrument almost as eccentric as Gould.

Gould insisted on using a battered old chair that had been sawed down so it was six inches shorter than a standard piano bench. He was a hypochondriac who insisted on keeping the room temperature at 80 degrees year-round, and once sued Steinway because an employee gave him an admiring pat on the back that he claimed had dislocated his shoulder, but his nose-to-the-keyboard posture must have caused many of the aches and pains of which he complained. He was a terrifying driver, who once quipped, “It’s true that I’ve driven through a number of red lights on occasion, but on the other hand I’ve stopped at a lot of green ones but never gotten credit for it.”

Hafner’s signal achievement in the book is to turn CD 318 itself into just as much a personality as Gould. Never mind that she has also demonstrated that CD 318 is just wood, steel, ivory and felt. We come to feel about CD 318 almost the way Gould did: “‘He talked about his piano as if it were human,’ fellow pianist David Bar-Illan commented.” So when CD 318 is injured in a fall … uh, damaged by being dropped, we’re shocked, and we especially empathize with Edquist, who has to break the news to Gould.

Hafner lives in the Bay Area, writes for the New York Times, and has published books about computer hackers and Internet pioneers, among other things. Some readers will complain that she touches too lightly on Gould’s faults: his undeniable gifts that were vitiated by self-indulgence; his interpretations that occasionally departed wildly from the composers’ intent; his decision to stop performing before audiences for the last 18 years of his life, and to concentrate on recording, in which mistakes can be edited out, making him appear to be technically flawless.

But the book is less a critique of Gould than an examination of an essential relationship, the one between artist and medium, as magnified by one artist’s obsession. Hafner’s book belongs to that gee-whiz genre perfected by writers like John McPhee, Susan Orlean and Mary Roach: books that tell you everything about subjects – oranges, orchids, corpses, pianos – that you didn’t know you wanted to know anything about. And for readers familiar with Gould’s recordings, or those with a curiosity about how things like pianos get to be the way they are, “A Romance on Three Legs” is a source of delight and illumination.