The Path

Running along a bank, a parapet

That saves from the precipitous wood below

The level road, there is a path. It serves

Children for looking down the long smooth steep,

Between the legs of beech and yew, to where

A fallen tree checks the sight: while men and women

Content themselves with the road and what they see

Over the bank, and what the children tell.

The path, winding like silver, trickles on,

Bordered and even invaded by thinnest moss

That tries to cover roots and crumbling chalk

With gold, olive, and emerald, but in vain.

The children wear it. They have flattened the bank

On top, and silvered it between the moss

With the current of their feet, year after year.

But the road is houseless, and leads not to school.

To see a child is rare there, and the eye

Has but the road, the wood that overhangs

And underyawns it, and the path that looks

As if it led on to some legendary

Or fancied place where men have wished to go

And stay; till, sudden, it ends where the wood ends.

--Edward Thomas

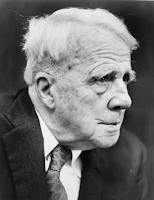

One of the great victims of the murderous nonsense that was World War I, Thomas wrote under the influence of Robert Frost, who said once that Thomas's regrets were the inspiration for "The Road Not Taken." I have to say that I like Thomas's directness more than Frost's irony -- when I read Frost I always have to ask "what's he really getting at?" I picked "The Path," of course, partly to contrast with "The Road Not Taken," but also because of its prophetic poignancy. The wood ended too soon for Thomas.