To an Old Philosopher in Rome

On the threshold of heaven, the figures in the street

Become the figures of heaven, the majestic movement

Of men growing small in the distances of space,

Singing, with smaller and still smaller sound,

Unintelligible absolution and an end --

The threshold, Rome, and that more merciful Rome

Beyond, the two alike in the make of the mind.

It is as if in a human dignity

Two parallels become one, a perspective, of which

Men are part both in the inch and in the mile.

How easily the blown banners change to wings ...

Things dark on the horizons of perception,

Become accompaniments of fortune, but

Of the fortune of the spirit, beyond the eye,

Not of its sphere, and yet not far beyond,

The human end in the spirit's greatest reach,

The extreme of the known in the presence of the extreme

Of the unknown. The newsboys' muttering

Becomes another murmuring; the smell

Of medicine, a fragrantness not to be spoiled ...

The bed, the books, the chair, the moving nuns,

The candle as it evades the sight, these are

The sources of happiness in the shape of Rome,

A shape within the ancient circles of shapes,

And these beneath the shadow of a shape

In a confusion on bed and books, a portent

On the chair, a moving transparence on the nuns,

A light on the candle tearing against the wick

To join a hovering excellence, to escape

From fire and be part only of that of which

Fire is the symbol: the celestial possible.

Speak to your pillow as if it was yourself.

Be orator but with an accurate tongue

And without eloquence, O, half-asleep,

Of the pity that is the memorial of this room,

So that we feel, in this illumined large,

The veritable small, so that each of us

Beholds himself in you, and hears his voice

In yours, master and commiserable man,

Intent on your particles of nether-do,

Your dozing in the depths of wakefulness

In the warmth of your bed, at the edge of your chair, alive

Yet living in two worlds, impenitent

As to one, and, as to one, most penitent,

Impatient for the grandeur that you need

In so much misery; and yet finding it

Only in misery, the afflatus of ruin,

Profound poetry of the poor and of the dead,

As in the last drop of the deepest blood,

As it falls from the heart and lies there to be een ,

Even as the blood of an empire, it might be,

For a citizen of heaven though still of Rome.

It is poverty's speech that seeks us out the most.

It is older than the oldest speech of Rome.

This is the tragic accent of the scene.

And you -- it is you that speak it, without speech,

The loftiest syllables among loftiest things,

The one invulnerable man among

Crude captains, the naked majesty, if you like,

Of bird-nest arches and of rain-stained vaults.

The sounds drift in. The buildings are remembered.

The life of a city never lets go, nor do you

Ever want it to. It is part of the life in your room.

Its domes are the architecture of your bed.

The bells keep on repeating solemn names

In choruses and choirs of choruses,

Unwilling that mercy should be a mystery

Of silence, that any solitude of sense

Should give you more than their peculiar chords

And reverberations clinging to whisper still.

It is a kind of total grandeur at the end,

With every visible thing enlarged and yet

No more than a bed, a chair and moving nuns,

The immensest theatre, the pillared porch,

The book and candle in your ambered room.

Total grandeur of a total edifice,

Chosen by an inquisitor of structures

For himself. He stops upon this threshold,

As if the design of all his words takes form

And frame from thinking and is realized.

--Wallace Stevens

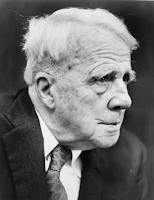

This is an inexhaustible poem, one that lends itself to readings and rereadings and yet never yields up everything within. The old philosopher of the title is George Santayana, whose last years were spent under the care of the nuns of a convent in Rome. When Stevens was a student at Harvard, he became acquainted with Santayana, who taught in the philosophy department. The usual way of explicating such a poem might be to try linking its ideas to Santayana's, but I really think Stevens is using the philosopher as a symbol of the thinking mind trying to make sense of the external world even as death is about to extinguish that mind. For me the key lines in the poem (as well as the most beautiful ones) are:

A light on the candle tearing against the wickThis is not a poem about raging against the dying of the light; it's about joining that light -- call it God, call it imagination, call it the Oversoul. Better yet, call it the celestial possible. Which is the earthly impossible.

To join a hovering excellence, to escape

From fire and be part only of that of which

Fire is the symbol: the celestial possible.