|

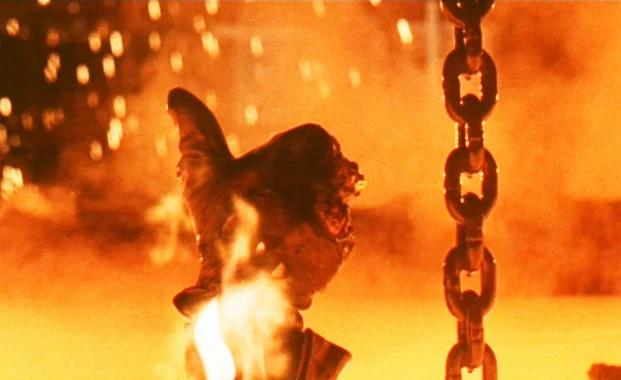

| Ralph Meeker and Carroll Baker in Something Wild |

A young woman is brutally raped on her way home, but she tells no one and next day tries to act as if nothing has happened until she is overcome by the crowds on the subway and faints. A policeman brings her home, where her self-centered mother is more concerned that the neighbors saw her in a police car than about her health. Unable to tolerate her mother's whiny self-centered behavior, she runs away, rents a tiny room in a dirty, run-down tenement, and gets a job as a clerk in a five-and-dime store. But her stand-offish behavior, the result of her distaste for being touched, annoys the other clerks, who ostracize her. Wandering aimlessly through the city streets, she finds herself on a bridge and, in a daze, starts to climb over the railing. She is stopped by a garage mechanic on his way to work, and he persuades her to come back to his basement apartment to rest. In her exhaustion, she agrees, but he later comes home from work falling-down drunk and attempts to rape her. She fights him off, kicking him in the eye when he's down, and he passes out. But she discovers that he has locked the door and she can't escape. When he awakes the next morning, he has no memory of attacking her and thinks that he must have sustained the eye injury in a fight at the bar. But when he leaves for work, he won't let her go and locks the door behind him. She becomes his prisoner, while he pleads for her love and eventually proposes marriage. So far, Jack Garfein's Something Wild succeeds as a harrowing, vivid portrait of lost lives in the city. Carroll Baker gives a fine performance as the young woman, Mary Ann, and Ralph Meeker shifts convincingly from tenderness to menace and back again as her captor, Mike. Mildred Dunnock makes the most of her role as Mary Ann's mother, and there are some good performances by future TV sitcom actresses Jean Stapleton and Doris Roberts, the former as the noisy prostitute who has a room next to Mary Ann's in the tenement, the latter as Mary Ann's co-worker at the five-and-dime, who leads the other clerks in shunning her. Best of all are the cinematography of Eugen Schüfftan, capturing New York City at its grandest and grimmest, and the edgy score by Aaron Copland. But just when things look the most hopeless for Mary Ann, Mike goes out one day without locking the door -- perhaps intentionally -- and she escapes. It's a beautiful spring day in the city and she wanders through Central Park, her spirits reviving, and returns to the apartment where she accepts Mike's proposal. Then it's Christmas and Mary Ann has sent a note to her mother telling where she now lives. The mother visits the basement apartment to plead with Mary Ann to return home, but Mary Ann tells her that this is now her home and moreover that she's pregnant. And on a moment that is fairly drenched with Hollywood-style sentiment, though this has been a fearlessly unsentimental and independently gritty movie, the film ends. I suppose it's possible to take this wrap-up as Garfein's parody of the Hollywood ending, but it's difficult to countenance the film's undercutting of itself any other way, not to mention that it seems to suggest that the trauma of rape can be "cured" by another kind of rape: imprisonment. Something Wild seems to me a collection of brilliant moments and skilled performances, and to provide a compelling portrait of urban alienation whose tone is set with the striking opening credits by Saul Bass. But by losing its integrity of vision at the end, it fails to be a whole film.