A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Thursday, May 19, 2016

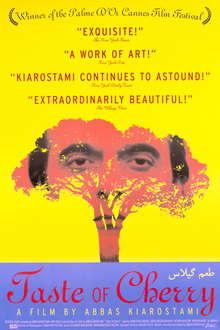

Taste of Cherry (Abbas Kiarostami, 1997)

I had never seen a film by Kiarostami before, though I knew he was a celebrated Iranian director, so I watched Taste of Cherry with a mostly unbiased eye. I say "mostly" because in his introduction on TCM Ben Mankiewicz commented that although the film won the Palme d'Or at Cannes and has a host of admirers, Roger Ebert found it "excruciatingly boring" and listed it as one of his "most hated films" on his web site. Having seen the film and read the review, I have to wonder if Ebert was in the wrong mood when he saw and wrote about it. I saw it in relaxed anticipation and found it anything but boring. Not a masterpiece, perhaps, but a strangely haunting film, whose images stayed with me through the following day: the winding dirt roads in the hills outside Tehran; the cascades of bare soil turned up by massive agricultural equipment; the shadow of the protagonist, Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi), projected upon these mounds of dirt; the faces of the men the protagonist tries to enlist in his plan: a young soldier (Safar Ali Moradi), a seminarian (Mir Hossein Noori), the taxidermist (Abdolrahman Bagheri). I was struck by the way Kiarostami chose to make those three men aliens in Iran -- a Kurd, an Afghani, a Turk -- as if to emphasize the inner turmoil that mirrors the external conflicts of the region. I was tantalized by the suspense about what Badii wants the other man to do, and as Ebert points out, the fact that we suspect that he is cruising the outskirts of Tehran to find a sexual partner. (Which, given that homosexuality is a capital offense in Iran, is a frighteningly risky thing to do.) And when we learn that Badii wants someone to throw dirt over him after he commits suicide in a grave he has dug for himself, I was intrigued by what has driven him to this brink. But I'm astonished that Ebert took such a literal-minded approach to all of this, wanting to know why we are being led to believe that Badii is gay and to know more about what has driven him to this extremity. Have we not learned long ago not to expect full backstories of characters in literature and film, or to be able to explicate them in some definitive sense? Isn't that why Kiarostami uses the "distancing" device at the end of showing the film itself being made? I'm content with what it tells us of Badii, and with the emotions and ideas demonstrated by the men he picks up: the young soldier's terror, the seminarian's steadfast faith, the taxidermist's hard-earned wisdom. I was struck by the way we watch Badii at the end through the window of his apartment, as if we will never get any closer, but then see his face as he lies in the hole fleetingly illuminated by lightning. But Taste of Cherry is not so much a character-driven film as a fable: a story about the mysteries of human existence and the interplay of lives. It is full of reverberations, not only of one scene with another but of the events in the film with the troubles -- political, social, environmental -- that haunt our times. It can't be reduced to conventional narrative or even allegorical terms. It took me someplace alien -- i.e., Iran, and the possible last day of a man's life -- and yet deeply, humanly familiar.