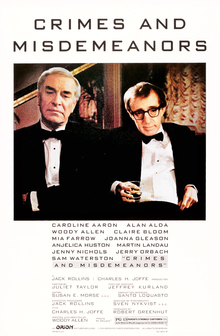

Crimes and Misdemeanors, a prime example of Woody Allen's mid-career films, has an impressive 8.0 rating on

IMDb and a 93% favorable critics' rating on

Rotten Tomatoes. Which surprises me, because I don't think it works. By this point, Allen had learned his lesson about trying to emulate Ingmar Bergman with such flops as

Another Woman (1988) and

September (1987), but he hadn't yet got Bergman out of his system. So what he does in

Crimes and Misdemeanors is to try to make a "cinema of ideas" -- in the manner of Bergman or

Robert Bresson or

Roberto Rossellini's Europa '51 -- while at the same time mocking his own effort to do so. He tells the story of the ophthalmologist Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau), who hires a hit man to kill his mistress (Anjelica Huston), who is threatening to expose their affair to Judah's wife (Claire Bloom). At the same time, Allen also tells the story of Cliff Stern (Allen), a documentary film-maker who wants to deal with serious subject matter but instead is forced to make a movie about his brother-in-law, Lester (Alan Alda), a glib, womanizing TV producer. Both Judah and Cliff are wrestling with the existentialist dilemma: In the absence of God, how do we determine what is right? Judah suffers pangs of guilt for his crime, recalling the fear of God placed in him by his Jewish upbringing, but he gets away with the murder and has evidently smothered his guilt by intellectually justifying it. Cliff meets and falls in love with Lester's charming associate producer, Halley (Mia Farrow), who is enthusiastic about the project Cliff has been working on: a profile of a philosopher, Louis Levy (Martin Bergmann), who has experienced suffering and worked his way to an apparent affirmation of life. But Cliff is fired after submitting a scathing first cut of the film about Lester, in which the producer is portrayed as Mussolini and as Francis, the talking mule. Then the life-affirming philosopher commits suicide, putting an end to Cliff's "serious" project. Judah and Cliff come together at the wedding of the daughter of Cliff's other brother-in-law, a rabbi named Ben (Sam Waterston), who happens to be one of Judah's patients and has been going blind throughout the film, accepting it as God's will. After telling Cliff his "idea" for a film -- essentially his own story -- and discussing the moral implications, Judah walks off happily with his wife, leaving Cliff, who has just heard Lester announce his engagement to Halley, very much alone. Yes, the ironies are as thick and heavy as that. There are strong performances from all the principals, including Jerry Orbach as Judah's brother, who arranges the hit, and Landau received a well-deserved supporting actor Oscar nomination. Allen's nominations as director and screenwriter are more iffy: He seems to me more an animator of ideas and ironies than a creator of living human beings.