A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Ben Chaplin. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Ben Chaplin. Show all posts

Thursday, November 24, 2016

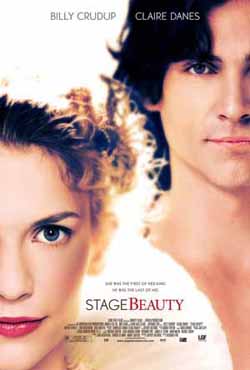

Stage Beauty (Richard Eyre, 2004)

It's a measure of how the discourse on sexual identity has changed over the past 12 years that Stage Beauty, in which it is a central theme, seems now to have missed the mark completely. Billy Crudup, an actor who should be a bigger star than he is, plays Edward Kynaston, an actor in Restoration London who was noted for his work in female roles at a time when such parts were usually still played by boys and men. Kynaston, as the film tells us, was praised by the diarist Samuel Pepys as "the loveliest lady that ever I saw in my life." As the film begins, he is performing as Desdemona in a production of Othello, and is aided by a dresser, Maria (Claire Danes), who longs to act. After his performance ends, she borrows his wig, clothes, and props, and performs in a local tavern as "Margaret Hughes." When King Charles II (Rupert Everett) lifts the ban on women appearing on stage, Kynaston not only finds his career threatened, but when the king's mistress, Nell Gwynn (Zoë Tapper), overhears him fulminating about the inadequacy of actresses, she persuades the king to forbid men from playing women's roles: The king gives as his reason that it encourages "sodomy." Although the actual Kynaston performed male as well as female roles, in the film he is stymied by an inability to act male parts. Eventually, Maria, who is having trouble with her own new career, calls upon Kynaston to coach her in his most famous role, Desdemona, while at the same time teaching him how to act like a man on stage. Together, they appear as Othello and Desdemona and, with a violently naturalistic performance of the death scene, bring down the house. The premise, taken from a play by Jeffrey Hatcher, who also wrote the screenplay, allows for some insight into the nature of gender, but the film never approaches it satisfactorily. Instead, we have a conventional ending that suggests not only that Kynaston and Hughes revolutionized acting with less stylized performance -- something that certainly didn't occur in the classically oriented Restoration theater -- but also that they fell in love. Earlier in the film, Kynaston is shown in a same-sex relationship with George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham (Ben Chaplin), who leaves him to get married. The film never quite resolves whether Kynaston is gay, bi, sexually fluid, or simply somehow confused by having been celebrated as a beautiful woman. And while it's risky to apply 21st-century psychology to 17th-century sexual mores, Stage Beauty's indifference to historical accuracy seems to demand that it do so. As unsatisfactory a film as it is, Stage Beauty has a few things to recommend it, starting with Crudup's fine performance. Danes is hindered by a screenplay that never concentrates on her character long enough to bring it into focus, but she and Crudup have strong chemistry together. And the supporting cast includes such British acting stalwarts as Everett, Chaplin, Tom Wilkinson, Richard Griffiths, and Edward Fox, as well as Hugh Bonneville, now best known for Downton Abbey, as Pepys. It's startling to see Robert Crawley, Earl of Grantham, peering out from beneath a Restoration periwig.

Saturday, December 12, 2015

The Wipers Times (Andy De Emmony, 2013)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)