A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Domhnall Gleeson. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Domhnall Gleeson. Show all posts

Thursday, November 17, 2016

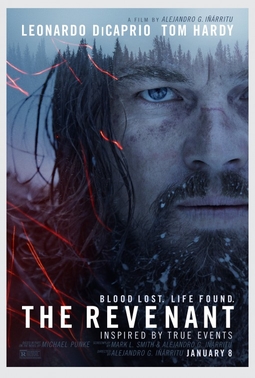

The Revenant (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2015)

I have suggested before, in my comments on Birdman (2014), Babel (2006), and 21 Grams (2003), that in Alejandro G. Iñárritu's films there seems to be less than meets the eye, but what meets the eye, especially when Emmanuel Lubezki is the cinematographer, as he is in The Revenant, is spectacular. The Revenant had a notoriously difficult shoot, owing to the fact that it takes place almost entirely outdoors during harsh weather, and it went wildly over-budget. Leonardo DiCaprio underwent significant hardships in his performance as Hugh Glass, the historical fur trader who became a legend for his story of surviving alone in the wilderness after being mauled by a grizzly bear. In the end, it was a major hit, more than making back its costs and getting strong critical support and 12 Oscar nominations, of which it won three -- for DiCaprio, Lubezki, and Iñárritu. I won't deny that it's an impressive accomplishment, and probably the best of the four Iñárritu films I've seen. It's full of tension and surprises, and fine performances by DiCaprio; Tom Hardy as John Fitzgerald, the man who leaves Glass to die in the wilderness; and the ubiquitous Domhnall Gleeson as Andrew Henry, the captain of the fur-trapping expedition who aids Glass in his final pursuit of Fitzgerald. Lubezki's cinematography, filled with awe-inspiring scenery and making good use of Iñárritu's characteristic long tracking takes, fully deserves his third Academy Award, making him one of the most honored people in his field. The visual effects blend seamlessly into the action, especially in the harrowing grizzly attack. And yet I have something of a feeling of overkill about the film, which seems to me an expensive and overlavish treatment of a tale of survival and revenge -- great and familiar themes that have here been overlaid with the best that today's money can buy. The film concentrates on Glass's suffering at the expense of giving us insight into his character. It substitutes platitudes -- "Revenge is in God's hands" -- for wisdom. And what wisdom it ventures upon, like Glass's native American wife's saying, "The wind cannot defeat the tree with strong roots," is undercut by the absence of characterization: What, exactly, are Glass's roots?

Tuesday, November 1, 2016

Star Wars: Episode VII -- The Force Awakens (J.J. Abrams, 2015) revisited

When I blogged about seeing Star Wars: Episode VII -- The Force Awakens, to give it its full and exhausting title, 10 months ago, I was more involved in the novelty of seeing it in a theater and in 3-D than in commenting on the film itself. "I look forward to seeing the movie again, but this time in the comfort of my home and on a smaller 2-D screen," I said then, predicting that it would "play just as well there." So the time has come, and Starz is running it almost every day on one of its many channels, so I availed myself of the opportunity, and I think I was mostly correct. The flat version is less awe-inspiring than the three-dimensional one, but I've long since got beyond the excitement of having lightsaber beams waved in my face, and to my mind the added depth of the images is counteracted by a sense of their insubstantiality: Is it only the force of long habit and familiarity that makes two-dimensional films seem more like documented reality? The 2-D Episode VII stands up because J.J. Abrams knows the grammar of film: the cutting and pacing that has brought excitement to movies ever since Griffith and Eisenstein and other first learned to use them. In 3-D there's always going to be something a little disorienting about the shift from a close-up to a long shot, for example. Perhaps a grammar of 3-D will be developed that lets filmmakers use it as effectively as they do in two dimensions, but that time has yet to come. As for the film itself, it had to do two things: It had to tie the new material to the core trilogy -- I mean Episodes IV-VI, of course -- and it had to whet our appetites for more new stuff. It succeeds on both counts, partly by bringing back Han (Harrison Ford), Leia (Carrie Fisher), and, albeit briefly, Luke (Mark Hamill), and the leitmotifs of John Williams's score, but also by pretty much shamelessly borrowing from what's now called Star Wars: Episode IV -- A New Hope (George Lucas, 1977). (I will always call it just Star Wars.) As I said in my first post, VII is pretty much a remake of IV: Both have "the young hero on a desert planet, the messenger droid found in the junkyard, the gathering of a team to fight the black-clad villain, and the ultimate destruction of a giant weaponized space station." VII also echoes the Oedipal conflict of the subsequent episodes of the core trilogy, with the conflict of father Han and son Kylo Ren (Adam Driver) echoing that of Darth Vader and Luke. What we have to look forward to is some account of Ren's (or Ben's) fall to the Dark Side and some resolution of that character's patricidal act. We also have to find out who or what Supreme Leader Snoke (Andy Serkis) is. Is there a little old man lurking behind what seems to be a hulking hologram, like the Wizard of Oz? And what are the backstories of Poe Dameron (Oscar Isaac), Finn (John Boyega), and Rey (Daisy Ridley)? And what accounts for the luxury casting of the ubiquitous Domhnall Gleeson as the relatively secondary figure General Hux? And why waste a beautiful Oscar winner like Lupita Nyong'o in voicing Maz Kanata -- another character whose backstory needs to be told? So our appetites are whetted, and not just for further adventures of Luke Skywalker.

Tuesday, October 11, 2016

Brooklyn (John Crowley, 2015)

This story about an Irish girl's coming of age has the strong whiff of traditional movie storytelling about it. And that's what makes it so entirely satisfying: It fulfills the need we often feel to be reassured about the stability of familiar things. But it also serves to support its theme, which is that nostalgia can be a trap, or to put it in a phrase that has become a cliché: You can't go home again. Eilis Lacey (Saoirse Ronan) feels stifled in her small Irish town, overshadowed by her pretty and accomplished sister, Rose (Fiona Glascott), and bullied by her vicious, hypocritical employer, Miss Kelly (Brid Brennan), so she decides to go to America. Helped by her church, she gets a room in a Brooklyn boarding house and a job in a department store, gradually loses her shyness and reserve, and falls in love with a sweet-natured young Italian American, Tony Fiorello (Emory Cohen). But when Rose dies suddenly, Eilis returns to Enniscorthy to see her mother and stays long enough to be courted by a young man, Jim Farrell (Domhnall Gleeson), and to begin to see the town in a very different light. The time approaches when she is scheduled to return to America, and she finds herself torn between not just Tony and Jim, but also the small but familiar comforts of the town and a promising but uncertain future in America. She also has a secret that she hasn't shared with anyone, but which the vicious Miss Kelly learns through the Irish-American grapevine. That this dilemma should play itself out with such freshness is a tribute to John Crowley's direction and Nick Hornby's adaptation of Colm Tóibín's novel, but also in very large part to a brilliant performance by Ronan. It's the kind of understated acting that sometimes gets overlooked among performances that chew the scenery with more fervor, but it earned Ronan a well-deserved Oscar nomination. It has to be said that she is supported by splendid performances by Cohen and Gleeson, with Ronan demonstrating a different kind of rapport with each actor. A quiet triumph, but a triumph nevertheless.

Monday, October 10, 2016

Anna Karenina (Joe Wright, 2012)

|

| Jude Law and Keira Knightley in Anna Karenina |

Alexei Karenin: Jude Law

Count Vronsky: Aaron Taylor-Johnson

Stiva Oblonsky: Matthew Macfadyen

Dolly Oblonskaya: Kelly MacDonald

Kitty Scherbatsakaya: Alicia Vikander

Konstantin Levin: Domhnall Gleeson

Countess Vronskaya: Olivia Williams

Princess Betsy: Ruth Wilson

Director: Joe Wright

Screenplay: Tom Stoppard

Based on a novel by Leo Tolstoy

Cinematography: Seamus McGarvey

Production design: Sarah Greenwood

Costume design: Jacqueline Durran

Anyone who wants to shake up an established film genre gets my support, even when what they do doesn't quite work. So I'm okay with what Joe Wright tries to do to the historical costume drama and the adaptation of a famous novel in his version of Anna Karenina. Which isn't to say that I think it works. What does work is the attempt by Wright and his screenwriter, Tom Stoppard, to redress the imbalance I've noted in my entries on two previous film adaptations of Tolstoy's novel, the ones directed by Clarence Brown in 1935 and Julien Duvivier in 1948: the neglect of the half of the novel that deals with Konstantin Levin. Domhnall Gleeson, the Levin of Wright's film, is hardly the Levin Tolstoy describes as "strongly built, broad-shouldered," but Gleeson seems to know what the character is about. And he's beautifully matched with Alicia Vikander, who gives another knockout performance as Kitty. Wright and Stoppard use their story as an effective foil for the obsessive, careless love of Anna and Vronsky. That it's only part of Levin's function in Tolstoy's novel, which gives us a view of Russian reform politics and social structure through Levin's eyes, just goes to show that you can't have everything when you're trying to adapt literature to a medium it isn't quite suited for. Wright has also cast brilliantly. As Karenin, Jude Law elicits sympathy for a character that can easily be reduced to a stock villain, as when Basil Rathbone played him in 1935. I also liked Matthew Macfadyen as Oblonsky, Anna's womanizing brother, and it's fun to see Macfadyen and Knightley together in completely different roles from Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet, whom they played in Wright's 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. As Anna, Knightley sometimes looks a bit too much like a gaunt fashion model in the Oscar-winning costumes by Jacqueline Durran, and Taylor-Johnson lays on the preening a bit too much in his bedroom-eyed Vronsky, but they have real chemistry together. Seamus McGarvey's Oscar-nominated cinematography makes the most of Sarah Greenwood's production design. But the decision to film the story partly as as if it were being staged in some impossible, dreamlike theater, but also partly realistically, goes astray. It begins as if it were a comedy, with the philandering Oblonsky sneaking around from his wife both onstage and backstage. And throughout the film, reversions from realistic settings to the theater keep jarring the overall tone. There are occasionally some spectacular uses of the set, as when the horses in Vronsky's race run across a proscenium stage, and in his accident, horse and rider plunge off the stage. Here and elsewhere, Greenwood's design is extraordinarily ingenious. But the theater trope -- all the world's a stage? -- never resolves itself into anything thematically satisfying.

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

Ex Machina (Alex Garland, 2015)

Screenwriter Alex Garland's debut as director has a lot going for it: a tightly provocative and suspenseful Oscar-nominated screenplay (also by Garland), a superb trio of stars, and special effects that don't overwhelm the story. The effects won Oscars for Andrew Whitehurst, Paul Norris, Mark Williams Ardington, and Sara Bennett, overcoming competitors with far more flash and dazzle: Mad Max: Fury Road (George Miller), The Martian (Ridley Scott), The Revenant (Alejandro González Iñárritu), and Star Wars: Episode VII -- The Force Awakens (J.J. Abrams). For once, special effects were kept on the human scale, largely to present Ava (Alicia Vikander) as the ambiguous cross between human being and robot on which the screenplay's exploration of the ethics of artificial intelligence depends. Ava (whose name is a variant spelling of "Eve") is the creation of Nathan (Oscar Isaac), a superwealthy tech genius who made his fortune with an Internet search engine not named Google, which he uses as the software for his experiment. He lures a young coder, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), to his isolated retreat on the pretext that he wants Caleb to apply the Turing test on Ava. Nathan's unstated aims are far more extensive, and Caleb sees through them quickly. But neither of them is quite as quick on the uptake as Ava. Gleeson is convincingly geeky as Caleb, and Isaac, in yet another performance that establishes him as one of our most chameleonic actors, evokes the self-absorption and questionable ethics of any number of tech billionaires. But it's Vikander who steals the honors with Ava's sly mixture of naïveté and nascent cunning. The only thing I can fault Ex Machina for is a conventional sci-fi ending that feels out of keeping with the intelligent questioning of the middle part of the script and seems too much like a setup for a sequel.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)