|

| Sean Connery and Tippi Hedren in Marnie |

Mark Rutland: Sean Connery

Sidney Strutt: Martin Gabel

Bernice Edgar: Louise Latham

Lil Mainwaring: Diane Baker

Mr. Rutland: Alan Napier

Susan Clabon: Mariette Hartley

Sailor: Bruce Dern

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Screenplay: Jay Presson Allen

Cinematography: Robert Burks

Film editing: George Tomasini

Music: Bernard Herrmann

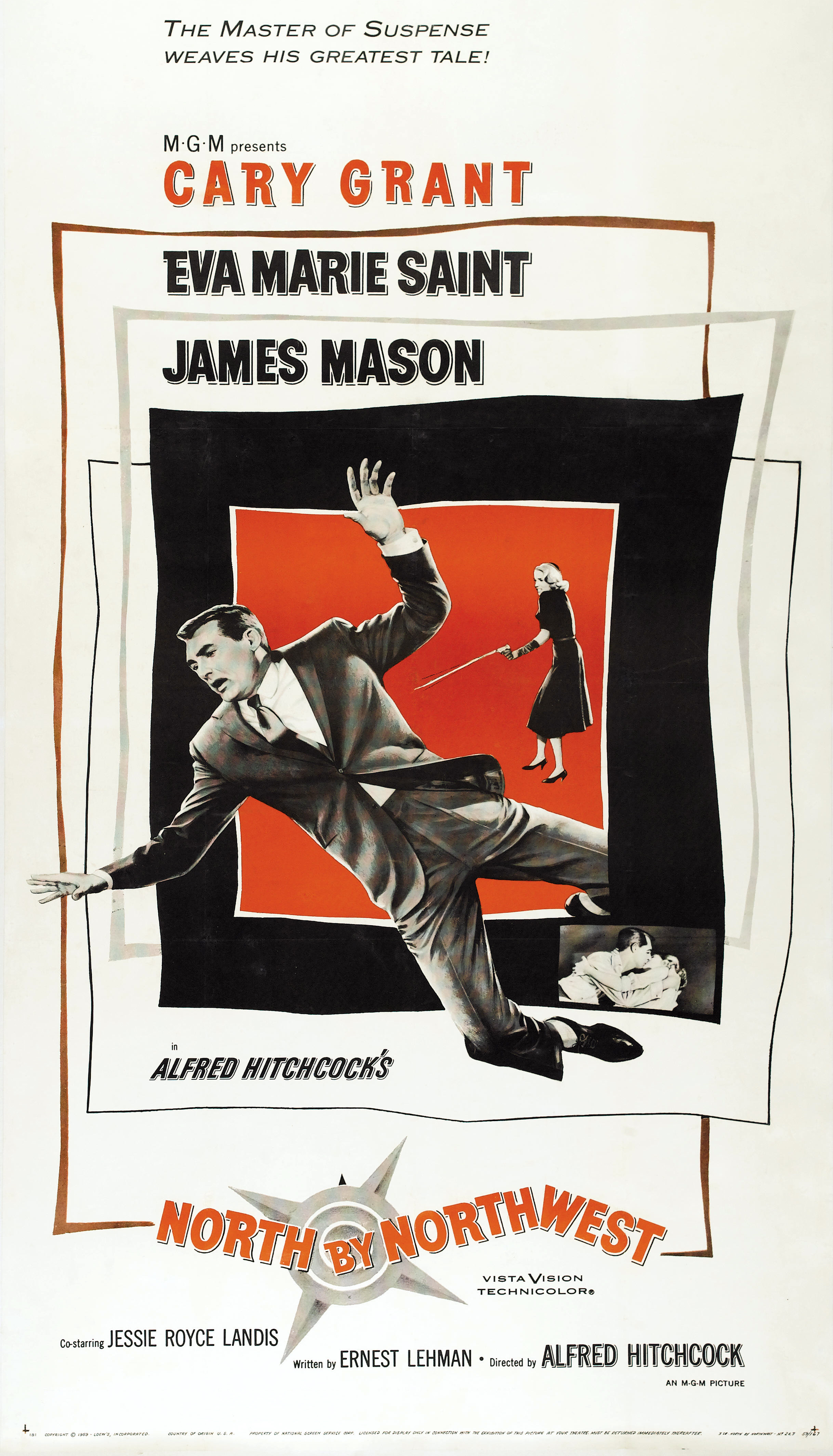

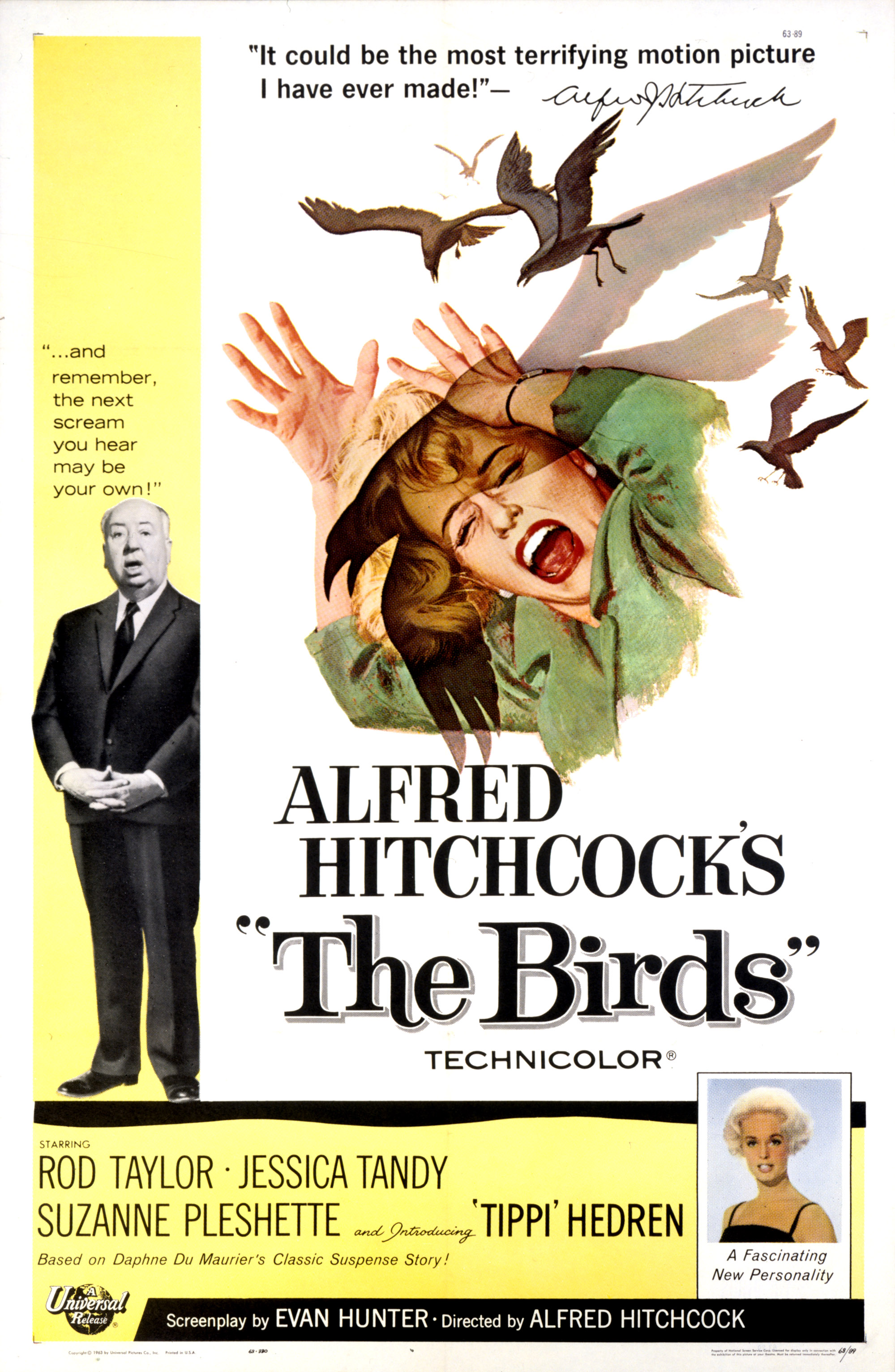

Marnie, once dismissed as just a stew of melodrama and pop psychology, has undergone a wholesale re-evaluation in recent years, much of it spurred by revelations about Alfred Hitchcock's sexual harassment of Tippi Hedren. Now it's often seen as not only one of his most revealing films about his personal obsessions -- second perhaps only to Vertigo (1958), which it much resembles -- but also one of his greatest. Its champions include the New Yorker's Richard Brody and filmmaker Alexandre Philippe. In the introduction to a recent showing of Marnie on Turner Classic Movies, Philippe even compared Hedren's performance to that of Isabelle Huppert in Michael Haneke's The Piano Teacher (2001). I wouldn't go that far. In fact, the most I'm willing to say is that Marnie is a very odd duck of a movie, one that just thinking about for a while can give me the creeps, especially in these times when each day seems to bring a new revelation about powerful men and their treatment of vulnerable women (and men). That's why the key to Marnie seems to me not so much Marnie herself but Mark Rutland. Hedren is very good in her role, fully playing up her character's ever-present self-consciousness, born of being the constant object of the male gaze. But the film turns on an actor's ability to make Mark's obsession with Marnie, his persistence in trying to treat her disorder, and the breakdown of his endurance when he rapes her into something both credible and meaningful. I doubt that even Hitchcock's most gifted leading men, i.e., Cary Grant and James Stewart, could have brought off the role with much success. Sean Connery brings his Bondian smirk to the part, which heightens our sense of Marnie's fear of men, but also undercuts what should be at least a plausible interest on his part of treating her illness. There's no gentleness in Connery's performance, so that even Mark's attempts to win her over -- buying her beloved horse, for example -- look like power plays. But Marnie's response to Mark is equally perverse: After the rape, she tries to drown herself in the ship's swimming pool, and when he asks why she didn't just jump overboard, she replies, "The idea was to kill myself, not feed the damn fish." Not only is the reply nonsensical but it also underscores the truth: The idea was obviously to let herself be found, either to be rescued or by her death to score another point against men. So it's clear that Marnie is the kind of film that invites exhaustive comment, which is not exactly the same thing as saying it's a great film, or even a good one. To my mind, it's a showcase of Hitchcockian technique without heart or wit. It has some fine touches, such as the scene in which Marnie goes to rob the Rutland safe and we watch as she goes about it on one side of the screen while on the other a cleaning woman comes closer and closer to discovering her. Once again, Hitchcock makes us root for someone who's doing something we should disapprove of, but there's also something overfamiliar about it: We saw something like it in Psycho (1960), when Norman tries and almost fails to sink the Ford containing Marion's body in the swamp. But there it was an important alienating moment; here it just seems like a trick to build suspense in a film that doesn't particularly need it. It's style for style's sake, the essence of decadence, and Marnie may be Hitchcock's most decadent film.

.jpg)