A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Go Kato. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Go Kato. Show all posts

Thursday, May 28, 2020

Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades (Kenji Misumi, 1972)

Cast: Tomisaburo Wakayama, Go Kato, Yuko Hama, Isao Yamagata, Michitaro Mizushima, Ichiro Nakatana, Akihiro Tomikawa. Screenplay: Kazuo Koike, Goseki Kojima. Cinematography: Chikashi Makiura. Art direction: Yoshinobu Nishioka. Film editing: Toshio Taniguchi. Music: Hiroshi Kamayatsu, Hideaki Sakurai.

There's no let-up to the bloodshed in the third installment of the Lone Wolf and Cub series: At the end, Ogami Itto (Tomisabuo Wakayama) stands alone in the middle of a corpse-strewn field, having vanquished an army of a couple of hundred men single-handedly -- or rather, with the help of little Daigoro and the baby cart, which is revealed to be a formidable fighting vehicle. But the most disturbing violence in the film is the rape of two women near the beginning of the film -- disturbing because it is treated realistically, rather than with the tricks of style that characterize the film's swordplay. The women are set upon by a gang of idlers, men waiting to be hired as fighters by whoever needs them. One member of the gang, however, holds himself aloof from the raping and pillaging that the others typically indulge in. He's Kanbei (Go Kato), a former samurai turned ronin, who is conscience-stricken, we learn, having been dishonored for an earlier failure to follow the orders of his lord to the letter, even though his actions saved the lord's life. This time, Kanbei remains loyal to the gang he has taken up with, and having come late to the scene of the rape, kills the two women and their servant, then has the three rapists draw straws to choose the one among them who will be killed as punishment for the rape. But just as Kanbei is killing the one who drew the short straw, Ogami comes upon the scene and kills the other two men. Kanbei challenges Ogami to a duel, but Ogami sheathes his sword and calls it a draw. What's going on here is a complex working out of the samurai code, which will resolve itself poignantly if bloodily at the end of the film when Ogami and Kanbei meet again. Which is to say that beneath the flash and dazzle of the multifarious violence of Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades, which includes an extended sequence in which Ogami is tortured to save a woman being sold into prostitution, lies a moral vision that's both alien and comprehensible.

Tuesday, September 24, 2019

Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance (Kenji Misumi, 1972)

Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance (Kenji Misumi, 1972)

Cast: Tomisaburo Wakayama, Fumio Watanabe, Go Kato, Tomoko Mayama, Yuko Hama, Shigero Tsuyuguchi, Asao Uchida, Taketoshi Naito, Yoshi Kato, Azami Ogami, Akihiro Tomikawa. Screenplay: Kazuo Koike, Goseki Kojima. Cinematography: Chikashi Makiura. Art direction: Akira Naito. Film editing: Toshio Taniguchi. Music: Eiken Sakurai, Hideaki Sakurai.

The Lone Wolf and Cub series, of which Sword of Vengeance is the first, has something in common with the Zatoichi films, such as Zatoichi and the Chest of Gold (Kazuo Ikehiro, 1964) and Kenji Misumi's own The Tale of Zatoichi (1962): They're about handicapped warriors traveling through hostile territory. Zatoichi is blind, whereas Ogami Itto is simply encumbered with a small child, his son. Yet somehow they beat the odds, fighting off whole armies out to get them. It's a good premise, made more suspenseful in the Lone Wolf films because we naturally don't want to see small children put in harm's way. Which Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance does from the very outset, in which Ogami, the official executioner, is forced to behead an infant, setting up the plot which leads him into a very real hell. Ogami is an intriguing character, which helped me put up with the somewhat routine villainy and violence of the film.

Friday, December 22, 2017

A Legend or Was It? (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1963)

|

| Kinuyo Tanaka and Shima Iwashita in A Legend or Was It? |

Yuri Shimizu: Mariko Kaga

Hideyuki Sonobe: Go Kato

Shiziku Sonobe: Kinuyo Tanaka

Shintaro Shimizu: Yoshi Kato

Goichi Takamori: Bunta Sugawara

Norio Sonobe: Tsutomu Matsukawa

Narrator: Osamu Takizawa

Director: Keisuke Kinoshita

Screenplay: Keisuke Kinoshita

Cinematography: Hiroshi Kusuda

Film editing: Yoshi Sugihara

Music: Chuji Kinoshita

Keisuke Kinoshita's A Legend or Was It? begins in an idyllic setting: a mountain valley in Hokkaido, gorgeously filmed in color, almost like a travelogue. But the narrator -- a rather obtrusive and unnecessary presence in the film -- tells us that it wasn't always inhabited by the kindly villagers we see going about their chores today. The setting remains the same as the film switches to black and white and we're told that it's now the summer of 1945. War is nowhere in evidence, but it's an inescapable presence. The villagers know that Japan is about to lose, and they're looking for ways to vent their frustration at having supported a losing cause. They find one in a family, the Sonobes, who have moved there after their home in Tokyo was bombed out. Suspicious and resentful of "city folk" on their turf, the villagers make the Sonobes a target after the daughter, Kieko, breaks off an engagement to Goichi Takamori, the son of the powerful mayor of the village, a wealthy landlord. Kieko's brother, on leave from fighting, has recognized Goichi, with whom he once served, as having killed and raped civilians, and urged Kieko not to marry him. In revenge, Goichi destroys the Sonobes' crops and begins spreading malicious rumors about them. A mob forms and a small-scale civil war breaks out. A Legend or Was It? is a highly kinetic film in its later parts, and the score by the director's brother, Chuji Kinoshita, helps create the kind of tension that needs to be released in action. Like Ennio Morricone, who punctuated Sergio Leone's "Man With No Name" trilogy (1964, 1965, 1966), with pennywhistle tweets and percussion, Chuji Kinoshita's score relies heavily on simple, perhaps even primitive instruments, setting up a pounding repetitive sound to propel the action. It has something of the hypnotic quality of Philip Glass's music, though without the variations that keep Glass's themes from complete monotony. Critics commenting on A Legend or Was It? sometimes compare it to Fritz Lang's Fury (1936) for its portrait of vigilante mob justice. It's an unforgiving film, without Kinoshita's typical lapses into sentimentality, and an effective one.

Saturday, September 30, 2017

The Young Rebels (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1980)

|

| Tomisaburo Wakayama in The Young Rebels |

Asakawa Senjo: Tomisaburo Wakayama

Takiko: Junko Mihara

Yukio: Tatsuya Okamoto

Orie: Tomoko Saito

Director: Keisuke Kinoshita

Screenplay: Keisuke Kinoshita

Cinematography: Masao Kosugi

The title of Keisuke Kinoshita's polemical pseudo-documentary, The Young Rebels, sounds like that of a Hollywood film from the 1950s, the era of naive, sensational, and didactic dramas about "juvenile delinquency." Which is exactly what The Young Rebels turns out to be: an exploitation film about why kids go wrong. The answer is a simple one: their parents. The kids, Kinoshita is saying, are not all right: They ride around on motorcycles, they cut school, they shoplift, and they have sex. This was not exactly news in 1980: Nagisa Oshima, for example, was onto these facts in 1960, when he made Cruel Story of Youth, and he blamed it on dysfunctional parenting in 1969's Boy. But Oshima's films are about people more than they are about problems. Kinoshita has lost sight of the people in his obsession with the problem, and the result is a scattershot film designed to ferret out examples of parental irresponsibility both high -- affluent parents who are so obsessed with climbing the corporate or social ladders that they either ignore their children or spoil them -- and low -- parents who are so mired in poverty and its attendant ills like alcoholism and crime that they abuse their children. The narrative framework of the film is as simplistic as its point of view: a journalist goes in search of answers and interviews children and parents. Kinoshita is enough of an artist that he knows how to tell the several stories uncovered by the journalist, which gives The Young Rebels enough dramatic substance to keep the polemic at bay during the storytelling, but the piling on of miseries turns into overkill. Eventually, the journalist visits a kind of reform school in Hokkaido, the north of Japan, where wayward boys are nurtured back into society -- but there's even some recidivism there. At the end, the point seems to be that every kid needs a loving mother and father -- the Japanese title translates as a cry for help: "Father! Mother!" It has been pointed out that people raised children for millennia until, sometime in the mid-20th century, they became self-conscious about it and turned it into a problem. Kinoshita's humorless and even hopeless polemic does little to solve the problem, especially when the film often seems bogged down in fogeyism: A scene of joyriding motorcycle gangs, for example, is treated as a vision from hell.

Friday, April 28, 2017

Children of Nagasaki (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1983)

|

| Yukiyo Toake* and Go Kato* in Children of Nagasaki |

Maria Midori Nagai*: Yukiyo Toake

Grandmother: Chikage Iwashima

Makoto*: Masatomo Nakabayashi

Director: Keisuke Kinoshita

Screenplay: Keisuke Kinoshita, Taichi Yamada, Kazuo Yoshida

Based on writings by Takashi Nadai

Cinematography: Kozo Okazaki

Music: Chuji Kinoshita

I've seen only three films by Keisuke Kinoshita, but it's clear from those three that the director was haunted throughout his life by the tragedy that militarism inflicted on his country. Morning for the Osone Family (1946) is a depiction of what one family, divided by its attitudes toward the war, went through during its waning years. Twenty-Four Eyes (1954) is a sentimental yet oddly powerful anti-war film that takes place in a pastoral setting virtually untouched by bombing raids, yet deeply wounded by the conflict just over the horizon. Children of Nagasaki was one of his last films, and also one of his least known in the West -- it has no reviews on Rotten Tomatoes, a link to only one review on IMDb, and no entry at all in Wikipedia. But of the three it's the only one that directly confronts the physical horror of the war. It's essentially a biopic of Takashi Nagai, a physician who survived the nuclear explosion in Nagasaki and devoted himself to writing about the event and its aftermath, using his training as a radiologist to document the effects of radiation. Most of Nagai's writing was censored by the occupation authorities and not published until after his death in 1951 from leukemia, with which he had been diagnosed before the bomb fell on Nagasaki. In the film, Nagai is at work when the bomb is dropped, killing his wife. His two children are in the country with their grandmother, and with her help he goes about the task of rebuilding their home and their lives. The film, which begins with scenes from the visit to Nagasaki by Pope John Paul II in 1981, is suffused with Nagai's Roman Catholic faith, and while it's not clear if Kinoshita shared Nagai's faith -- the director is buried in a Buddhist cemetery -- he treats it with deep respect, even reverence. Children of Nagasaki is an uneven film, a little too heavily didactic, as the literally preachy use of the pope to open the film suggests. Three-quarters of the way in, Kinoshita suddenly and clumsily switches to a narrator, Nagai's grown son, reflecting on the life of his father. But he makes one striking choice: not to depict the horrors inflicted on the people of Nagasaki by the bomb at the point in the narrative when they occur, but instead to show them at the end of the film in a flashback, reinforcing the point that such a story can't really have a happy ending.

*These identifications are unconfirmed. IMDb lists only cast members and not the names of the roles they play. I've resorted to guesswork based on other sources in making the identifications. Corrections are welcome.

Friday, December 2, 2016

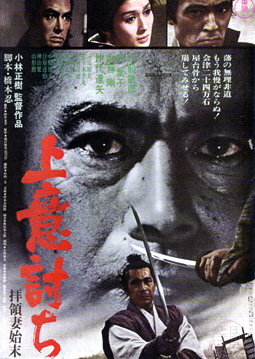

Samurai Rebellion (Masaki Kobayashi, 1967)

Like his Harakiri (1962), Kobayashi's Samurai Rebellion has a theatrical, almost Shakespearean quality and is sharply critical of the samurai code of honor. Toshiro Mifune plays Isaburo, a samurai whose son Yogoro (Go Kato) is ordered to marry the concubine Ichi (Yoko Tsukasa) of the daimyo of the clan he serves. Yogoro is reluctant, partly because Ichi has a son by the daimyo, but eventually they fall in love. Unfortunately, the daimyo's older son dies, making Ichi's child the heir, and she is ordered to return to his household. The ensuing rebellion against the daimyo's order proves calamitous for all concerned. The beautifully committed performances by all concerned heighten the story's tragic drive. The film's English title was apparently designed to convince Western audiences that they were going to see a conventional samurai film, whereas it's really a story about the heroism of Ichi, giving a distinctly feminist spin to the genre.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)