A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Holly Hunter. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Holly Hunter. Show all posts

Wednesday, November 16, 2016

O Brother, Where Art Thou? (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2000)

On the scale for goofy Coen brothers films, O Brother, Where Art Thou? falls somewhere between Raising Arizona (1987) and The Big Lebowski (1998) from goofiest to least goofy. It is, I think, more over-the-top than is absolutely necessary, especially in the idiot hick accents adopted by John Turturro and Tim Blake Nelson in their roles. Or maybe they just seem that way because of the differently over-the-top performance of George Clooney as Ulysses Everett McGill, a man who thinks he talks more intelligently than he does. Still, I like Clooney in this mode, more than I do when he's playing a serious character, and it's to the Coens' credit that they cast him in the role: His performance gives an odd kind of off-balance stability to that of the other two. The chief glory of the movie, however, is its music, chosen by T Bone Burnett, superbly evoking a time and place. As for that time and place, Depression-era Mississippi, the movie pretty much ignores reality in favor of goofing around. It was the era of Bilbo and Vardaman, politicians of deeply cynical evil, and the rival candidates played by Charles Durning and Wayne Duvall don't even approach their horror, even when lampooning it. I laughed when the Ku Klux Klan performed what looked like a marching band half-time routine with a chant that evokes the parading monkey guards in The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), but maybe it's the outcome of the recent presidential election that made me feel a little nauseated at even the notion of a comical Klan. A kind of irresponsibility mars the Coens' approach to the material, brilliantly funny as it often is. That said, the pacing of the movie is lively, and it's filled with ever-watchable performers like Durning, Holly Hunter, and John Goodman at their best. And there's always that music: If I'm inclined to forgive the Coens for their irresponsibility, it's because they introduced a lot of people who went out and bought the soundtrack album to some great music.

Friday, March 25, 2016

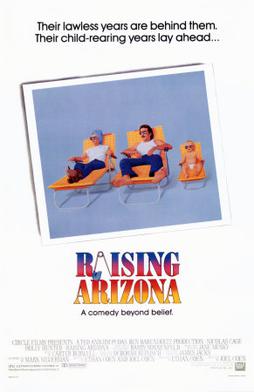

Raising Arizona (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 1987)

Raising Arizona was the Coen brothers' second movie, and they never made another quite as broadly comic as this one. Even The Big Lebowski (1998) and O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) seem restrained in comparison. I found that it took a little getting used to on this viewing: Everyone in it (including the baby) is a caricature, a live-action version of a Warner Bros. cartoon character. Maybe I reacted this way because I recently saw Holly Hunter in the deadly serious role of Ada in The Piano (Jane Campion, 1993) and had forgotten what a gifted farceuse she could be when she sets her tight little mouth in that determined line and barrels ahead. Nicolas Cage was still in that goofy hangdog persona he used in Peggy Sue Got Married (Francis Ford Coppola, 1986) and only began to grow out of the next year in Moonstruck (Norman Jewison, 1987). But the real surprise for me was Frances McDormand, going completely over the top as Dot, the scatterbrained mother of the most odious bunch of brats ever seen on film. She was at the beginning of her career as a serious actress and would follow up Raising Arizona with her first Oscar nomination for Mississippi Burning (Alan Parker, 1988), so seeing her go all loosey-goosey in this film was a revelation. It's by no means among my favorite Coen brothers movies, and watching it in the company of their best -- among which I'd put Fargo (1996), No Country for Old Men (2007), and Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) -- would probably show up some of its flaws, but why would you want to do that? Sometimes silly fun is enough. At only a touch over an hour and a half, Raising Arizona doesn't hang around long enough to wear out its welcome.

Tuesday, March 22, 2016

The Piano (Jane Campion, 1993)

If Jane Campion had gone with her original plan, Ada (Holly Hunter) would have gone down with her piano like Ahab lashed to the whale. The comparison to Moby-Dick is not, I think, terribly far-fetched: The Piano is one of those works, like the Melville novel, that tempt one into symbolic interpretations. Ada's obsession with her piano is, in its own way, like Ahab's obsession with the white whale, a kind of representation of the extreme irrational nexus of mind and object. But in Campion's completed version, Ada loses only a finger, not her life, and the piano is replaced along with the finger. Does this resort to a happy ending vitiate Campion's film, or should we accept as a given that life does in fact sometimes work that way? I think in a movie as enigmatic as The Piano so often is, Campion has blunted the emotional impact by having Ada and Baines (Harvey Keitel) wind up together in what seems to be a pleasant home far from the wilderness in which most of the film takes place, she teaching piano with her hand-crafted prosthetic and learning to speak, as Flora (Anna Paquin), that devious, semi-feral child, turns cartwheels. (Flora puts me in mind of another child of the wilderness in another work of impenetrable symbolism, Pearl in The Scarlet Letter.) Happily ever after seems like a lie in the mysterious terms with which the film began. We never learn why Ada turned mute, or who Flora's father was and what happened to him, or why she agrees to move to New Zealand to marry and then spurn Stewart (Sam Neill), or find a way to resolve any number of other enigmas. But the great strength of the film lies its power to evoke the imponderable, to make us wonder about Baines's life among the Maori, about the persistence of an imperialist culture (women wearing hoopskirts and men in top hats) in an alien land, about the nature of awakening sexuality, about the function of art, about the tension between innocence and experience in a child's life, and so on. It is, I'm certain, a great film, just because it is so hard to grasp and reduce to a formula.

Links:

Anna Paquin,

Harvey Keitel,

Holly Hunter,

Jane Campion,

Sam Neill,

The Piano

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)