A Page of Madness (Kurutta ippêji), Teinosuke Kinugasa, 1926

|

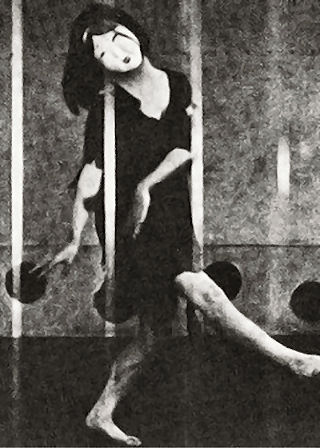

| Eiko Minami in A Page of Madness |

Servant: Masao Inoue

Servant's Daughter: Ayako Iijima

Servant's Wife: Yoshie Nakagawa

Young Man: Hiroshi Nemoto

Doctor: Misao Seki

Dancer: Eiko Minami

Director: Teinosuke Kunugasa

Screenplay: Yasunari Kawabata, Teinosuke Kinugasa, Minoru Inozuka, Banko Suwada

Based on a story by Yasunari Kawabata

Cinematography: Kohei Sugiyama

Art direction: Chiyo Ozaki

Once again, my thanks to Turner Classic Movies for programming this fascinating film. But this time I have to temper the thanks with a complaint about Ben Mankiewicz as host. Not only did he mispronounce the director's name (as "Kinagusa") but he also failed to give much substantial information about the film's content beyond noting that it was thought to have been lost until Kinugasa discovered it in 1971, and that the film's style was influenced by the German Expressionism of

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920), which preceded it on TCM. Given that the film plays without intertitles, it would have been helpful if Mankiewicz had indicated something of the film's storyline. Apparently, Japanese silent movies relied on

benshi -- live narrators who told the story and sometimes supplied dialogue for the on-screen players. Watching

A Page of Madness without such an aid is challenging, especially since the first portion of the film is largely composed of a montage of images that establish the atmosphere of the film and its setting, an insane asylum. Eventually I became aware that there was a central story about a janitor (Masao Inoue) in the asylum and his involvement with a particular female inmate (Yoshie Nakagawa) and a woman (Ayako Iijima) who visits the madhouse. But I had to turn to the

Internet to learn that the woman is the janitor's wife and the visitor his daughter. However, much of the plot, based on a story by Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata, remains enigmatic, subordinate to the power of the images supplied by cinematographer Kohei Sugiyama and art director Chiyo Ozaki. But it's still exciting to watch, not only for the bizarrely evocative camerawork but also for Kinugasa's direction, which includes a riot in the asylum. He is best known in the West for

Gate of Hell (1953).

The Idiot (Hakuchi), Akira Kurosawa, 1951

|

| Masayuki Mori and Setsuko Hara in The Idiot (Hakuchi) |

Taeko Nara: Setsuko Hara

Kinji Kameda: Masayuki Mori

Denkichi Akama: Toshiro Mifune

Ayako: Yoshiko Kuga

Ono: Takashi Shimura

Satoko: Chieko Higashiyama

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Screenplay: Eijiro Hisaita, Akira Kurosawa

Based on a novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Cinematography: Toshio Ubukata

Production design: Takashi Matsuyama

I read Dostoevsky's

The Idiot a few months ago, so I was glad when Turner Classic Movies programmed Akira Kurosawa's film based on the novel. It's prime early Kurosawa, made in the year after

Rashomon and the year before

Ikiru, with the stars of the former, Masayuki Mori and Toshiro Mifune, in the respective roles of Kameda (the novel's Prince Myshkin) and Akama (the novel's Rogozhin). And Takashi Shimura, the star of

Ikiru, has the key role of Ono, the novel's General Yepanchin. Setsuko Hara, best known for her work with Yasujiro Ozu, is the "kept woman" Taeko Nasu, the novel's Nastassya Filippovna. So it's something of an all-star affair, originally designed as a two-parter. After a flop opening, the studio forced Kurosawa to cut it from its original run time of 256 minutes to the extant 166-minute version. It became something of a brilliant ruin in the process. As a recent reader of the novel, I appreciate the faithfulness with which Kurosawa stuck to Dostoevsky, while adapting the 19th-century Russian characters and setting to postwar Japan. Mori is, I think, an almost ideal Kameda/Myshkin. The raw edges from the cutting of the film show, however -- it's hard to follow the logic of some the characters' actions, and the presence of the mob that shows up with Rogozhin at one key point in the story goes unexplained in the film. The complex relationship among Takeda, Taeko, and Ono's daughter Ayako (the novel's Aglaya Ivanovna) becomes reduced to a kind of love triangle. But there are few sequences in Kurosawa as haunting as the candlelight vigil Kameda and Akama keep over the body of Taeko at the film's end.