|

| Lillian Gish in The Wind |

Lige: Lars Hanson

Roddy: Montagu Love

Cora: Dorothy Cumming

Beverly: Edward Earle

Sourdough: William Orlamond

Director: Victor Sjöström

Screenplay: Frances Marion

Based on a novel by Dorothy Scarborough

Cinematography: John Arnold

Art direction: Cedric Gibbons, Edward Withers

Film editing: Conrad A. Nervig

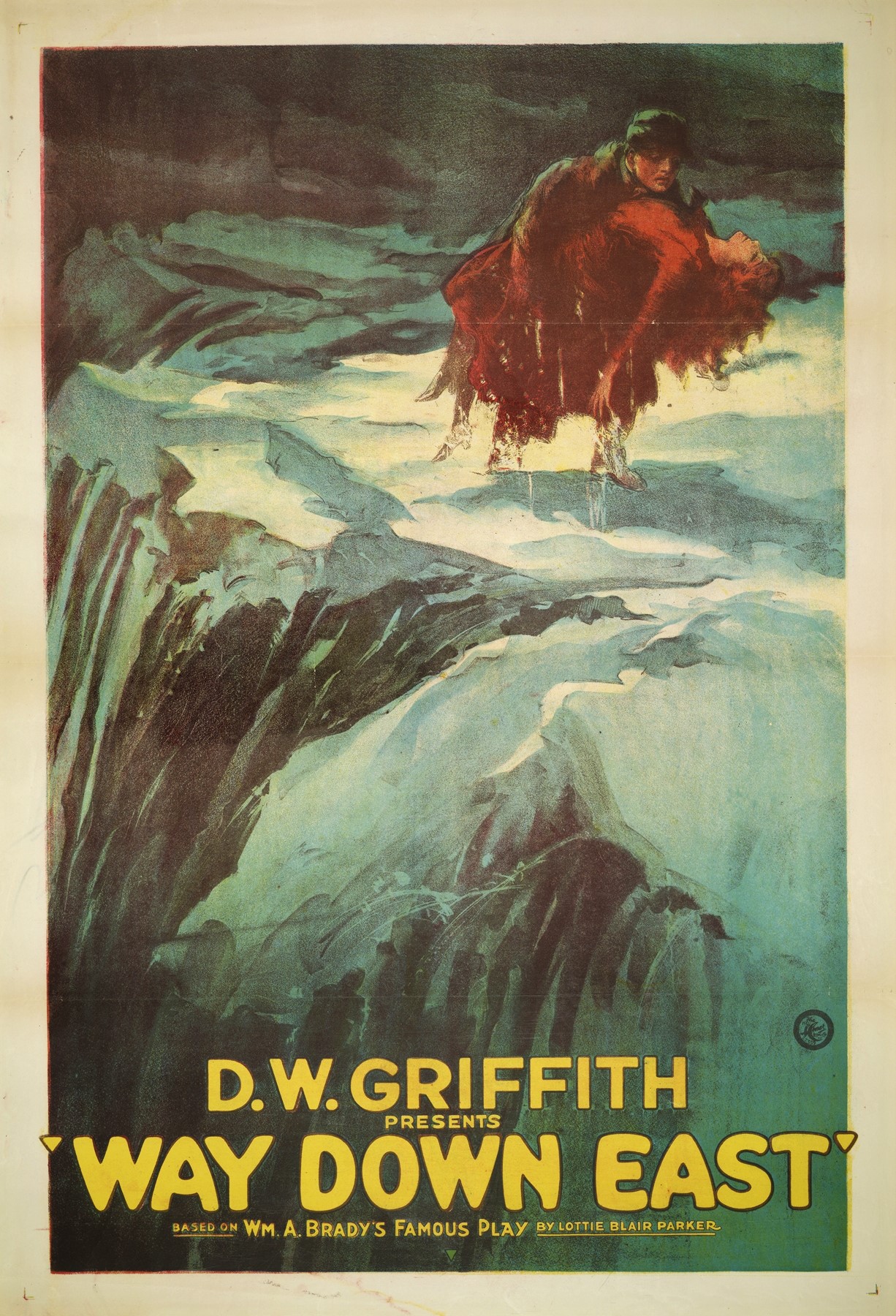

In the introduction to the 1983 video release of The Wind, produced by David Gill and Kevin Brownlow, Lillian Gish says that she and director Victor Sjöström (credited as "Seastrom" in his Hollywood years) argued for a downer ending to the film in which Letty, driven mad by the wind after she shoots Roddy, who has raped her, walks out into the whirling sandstorm to die. But Irving Thalberg, MGM's production head, insisted on the extant "happy ending," worried that their ending would hurt the film at the box office, with audiences already rejecting silent movies after the arrival of sound. It makes a good story, a fable about art vs. commerce. But as a friend of mine discovered when he interviewed Gish extensively about her work with D.W. Griffith, she was not always a terribly reliable source, given to telling stories long on color but short on accuracy. And I have to think that Thalberg was right about the ending of The Wind, not just because of its commercial value, but also because the concluding reconciliation of Letty and Lige feels consistent with the melodramatic story. As I've said before, drama should make you think, melodrama should make you feel. And in the absence of any real ideas to think about in The Wind, feeling bummed about the bleakness of the ending Gish and Sjöström proposed hardly makes for a satisfactory melodrama. The Wind has been hailed as a masterpiece, which I think it falls just short of being, largely because it becomes a one-woman show for Gish. She is superb, of course, but she's virtually the only character in the film with any dimensions: Roddy is a mustached rotter; Lige is a rural goof with a cornpone sidekick named Sourdough; Cora is a shrew and Beverly is a wimp. So we spend the film's 79 minutes watching Gish suffer brilliantly, responding in wholly affecting ways to the hopelessness of her life with a man she doesn't love, the bleakness of the landscape, and the constant torment of the wind. It's Gish as a grownup version of the waif she so often played for Griffith. But the film needs another substantial character: Lars Hanson is good so far as his role goes, but the screenplay stints on giving Lige a convincing character arc, from goof to spurned husband and finally to romantic hero. It's Letty who does all the heroic stuff, including shooting Roddy and trying to bury his corpse, so the reconciliation at the end, with both of them facing the wind, feels awfully one-sided. We may celebrate this as a tribute to the strong woman, but on the other hand it also feels like the wife submitting to duty to her husband.

.jpg)