|

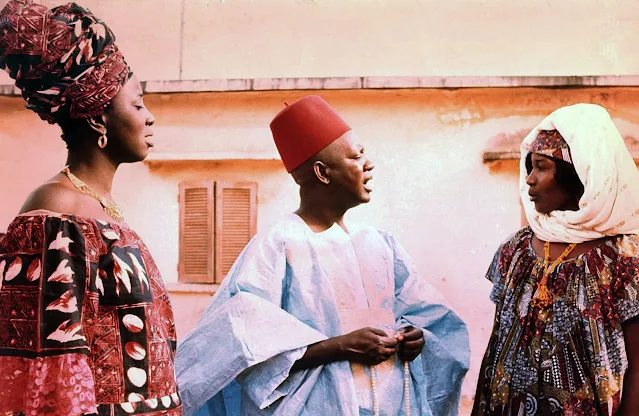

| Thierno Ndiaye and Mame Ndoumbé Diop in Guelwaar |

Cast: Thierno Ndiaye, Mame Ndoumbe Diop, Omar Seck, Ndiawar Diop, Marie Augustine Diatta, Moustapha Diop, Babacar Faye, Sadara Mbaye. Screenplay: Ousmane Sembene. Cinematography: Dominique Gentil. Film editing: Marie-Aimée Debril. Music: Baaba Mal.

The protagonist of Ousmane Sembene's sharply ironic tragicomedy Guelwaar is postcolonial Africa itself, viewed with a mixture of hope and frustration like that of the Europeanized Barthelemy (Nidiawar Diop) in the film, who often utters an exasperated "Africa!" when he encounters bureaucratic and cultural roadblocks in his attempt to bury his father. Actually, Barthelemy is trying to re-bury his father, Pierre Henri Thioune (Thierno Ndiaye), a political activist called by his followers "Guelwaar" (noble one), who died following a beating by political opponents. His body was mistakenly removed from the morgue and buried in a Muslim cemetery. Although Pierre Henri was a Catholic, the heads of the Muslim community don't want the grave disturbed to verify the identity of the corpse. The expatriate Barthelemy is not the best person to handle the problem, attracting suspicion from the authorities because he has become a French citizen, but he's the only member of the family capable of taking charge: His widowed mother, Nogoy Marie (Mame Ndoumbé Diop), is prostrate with grief; his sister, Sophie (Marie Augustine Diatta), is a sex worker in Dakar, and hence something of an outcast; and his younger brother, Alois (Moustapha Diop), is handicapped, crippled after a fall from a tree. Tensions build between Catholics and Muslims, and ultimately troops are called in by the area's representative in the legislature to keep violence from breaking out. Sembene tells the story beautifully, if occasionally resorting to the kind of blatant expository dialogue and didactic commentary aimed at his audience. Pierre Henri's radical politics center on an issue that reminds us how the causes of both right and left can sometimes converge: foreign aid to developing counties. He opposes the shipments of supposedly humanitarian aid such as food to his country, seeing it a tool used by foreign governments to gain influence, a cause of corruption in the government that distributes it, and a hindrance to the growth of a self-sustaining Africa. Sembene clearly endorses that view when, at the very end of the film, the young followers of the Guelwaar tear open the bags of rice and flour and the procession of carts carrying the funeral entourage drives over the spillage in an ironic triumph. With its keen portrayal of religious tensions, corruption, bureaucracy, and economic hardship, Guelwaar is a fine satiric blend of humor and pain, one of Sembene's best films.