|

| John Vernon and Karin Dor in Topaz |

Michael Nordstrom: John Forsythe

Nicole Devereaux: Dany Robin

Rico Parra: John Vernon

Juanita de Cordoba: Karin Dor

Jacques Granville: Michel Piccoli

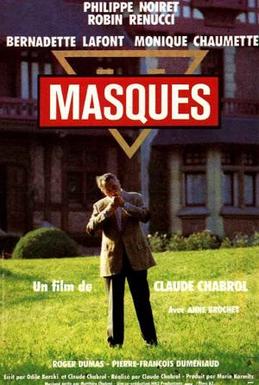

Henri Jarré: Philippe Noiret

Michele Picard: Claude Jade

François Picard: Michel Subor

Boris Kusenov: Per-Axel Arosenius

Philippe Dubois: Roscoe Lee Browne

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Screenplay: Samuel A. Taylor

Based on the novel by Leon Uris

Cinematography: Jack Hildyard

Music: Maurice Jarre

There's one Hitchcockian touch, almost the only one, in Topaz, that's become known as "the purple dress scene": As a woman, shot at close range, collapses to the floor, the skirts of her dress spread out around her like blood. It's a striking effect, but also a distractingly showoffy one in a film that is remarkably free of other such irruptions of style. Topaz may not be the worst film Alfred Hitchcock made -- there are some strong contenders in his early silents as well as in some of his other late films -- but it's certainly one of the dullest. There are four sections that cry out for some of the Hitchcock wit to make them more tense and entertaining: In the opening sequence, we watch as a highly placed official in the KGB defects to the West, along with his wife and daughter; then the French agent Andre Devereaux is tasked with retrieving a crucial document from a Cuban officer residing in a Harlem hotel during the opening of the United Nations; next, Devereaux goes to Havana to obtain further information about Russian missiles in Cuba (the film is set in October 1962); and finally, Devereaux is charged with unmasking the high-ranking French intelligent agents, whose code name is Topaz, who are selling secrets to the Soviets. Staging all of these sequences should have been child's play to the director whose mastery of the spy thriller was well-established in such films as Notorious (1946) and North by Northwest (1959), but each of them somehow fizzles into overextended business without real suspense. Part of the problem seems to be that Hitchcock was working without a finished script: After Leon Uris's attempt to adapt his novel was rejected, Hitchcock turned at the last minute to Samuel A. Taylor, who had written the screenplay for Vertigo (1958). Whatever you may think of Vertigo, the strengths of that film are not in its screenplay, and Taylor, working under intense deadline pressure, was unable to come up with a script that successfully ties together the four big sequences of Topaz. The frustration and ennui that Hitchcock felt with the situation is palpable. The ending was reshot several times, the first time after a preview audience rejected the notion of a duel between Devereaux and the Topaz agent Henri Jarré that took place in a soccer stadium, the second after audiences were confused by a scene in which Jarré manages to escape to the Soviet Union. The final version, in which Jarré commits suicide off-screen, lands with a thud, partly because Philippe Noiret, who played Jarré, was unavailable for the filming, so that we see only the exterior of his house and hear the sound of a gunshot. More interesting stars than Frederick Stafford and John Forsythe would have helped the film, but most of the blame for the dullness of Topaz has to be given to Hitchcock.