|

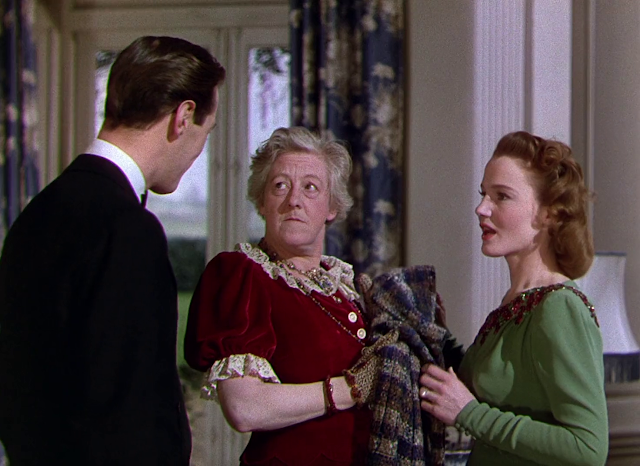

| Robert Newton, Wendy Hiller, Robert Morley, Rex Harrison, and Emlyn Williams in Major Barbara |

George Bernard Shaw's plays often seem to me as if they're about to collapse underneath their own cleverness: so many paradoxes, so much witty dialogue, such tantalizingly heretical ideas. Major Barbara is a prime example of this, a duel between faith and realism, between rich and poor, between capitalism and Fabian socialism, between men and women, all treated with the would-be drawing-room-comedy lightness of Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest, down to the climactic revelation that the play's ostensible hero is a "foundling" (a euphemism for "bastard"). But the film version slumps down into tedium because Shaw can't resist trying to make his characters, especially Barbara (wonderfully played by Wendy Hiller), into something like real people whenever he wants the audience to feel something instead of just laughing at the bright repartee. The film remains a three-act play, despite attempts to provide some scenes -- the initial meeting of Barbara and Adolphus Cusins (Rex Harrison being archly ardent), the fight between Bill Walker (Robert Newton) and Todger Fairmile (Torin Thatcher), Barbara's tossing her Salvation Army bonnet (and almost herself) into the Thames, and the tour of the hellish munitions factory and its heavenly benevolent-capitalist planned community -- in between the ones we would ordinarily see on stage. We are supposed to continue the dialogue of ideas among ourselves after the movie's over, but the effect of the two-hour-plus barrage of wit is to make me want to be stupid again. The film was rightly celebrated for the skill of its performers and for the tenacity with which it was filmed during the Blitz, but as a whole it's an achievement that hasn't stood the test of time.