|

| Ryunosuke Tsukigata and Susumu Fujita in Sanshiro Sugata |

Shogoro Yano: Denjiro Okochi

Sayo Murai: Yukiko Todoroki

Gennosuke Higaki: Ryunosuke Tsukigata

Hansuke Murai: Takashi Shimura

Osumi Kodana: Ranko Hanai

Tsunetami Iinuma: Sugisaki Aoyama

Police Chief Mishima: Ichiro Sugai

Saburo Monma: Yoshio Kusugi

Buddhist Priest: Kokuten Kodo

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa

Based on a novel by Tsuneo Tomita

Cinematography: Akira Mimura

Art direction: Masao Tozuka

Film editing: Toshio Goto, Akira Kurosawa

Music: Seiichi Suzuki

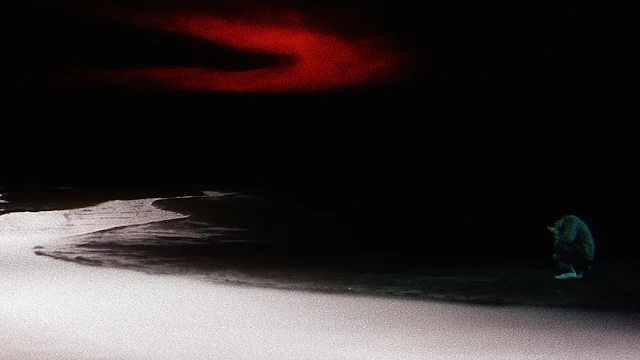

You know the plot: A talented, cocky young newcomer takes on the old pros and gets his ass kicked, but he learns self-discipline and becomes a winner. You've seen it played out with young doctors, lawyers, musicians -- it's even the plot of Wagner's Die Meistersinger -- and others challenging the established traditions. But mostly it's the plot for what seems to be about half of the sports movies ever made, including Akira Kurosawa's first feature, Sanshiro Sugata. It's also a film about the conflict between rival martial arts disciplines, jujitsu and judo, but fortunately you don't need to know much about the nature of the conflict to follow the film. From what I gather from reading the Wikipedia entry on judo, the founder of that discipline, Jigoro Kano, wanted to give jujitsu a philosophical underpinning that would put an emphasis on self-improvement for the betterment of society, and he called it judo because "do," like the Chinese "tao," means road or path. Kano's renaming was meant to shift the emphasis from physical skill to spiritual purpose. In Kurosawa's film, young Sanshiro comes to town wanting to find someone to teach him jujitsu, and signs up with a teacher who accepts a challenge from the judo master Shogoro Yano. (The name is an obvious twist on "Jigoro Kano.") Sanshiro watches as not only the teacher but all of the other members of his dojo are defeated -- in fact, tossed into the river -- by Yano. Whereupon Sanshiro becomes a follower of Yano's, but has to undergo some defeats and a cold night spent in a muddy pond before he gets the idea of what judo is all about. The film was not a big hit with the wartime Japanese censors, who wanted more aggression and less philosophy in their movies, so 17 minutes were cut from it, never to be seen again. In the currently available print, the missing material is summarized on title cards, but what's left is more than enough to show that Kurosawa arrived on the scene as a full-blown master director. His camera direction is superb, and he knows how to tell a story visually. For example, when Sanshiro joins up with Yano, he kicks off his geta, his wooden clogs, so he can pull Yano's rickshaw more efficiently. Kurosawa cuts to a passage-of-time montage in which we see one of the abandoned geta lying in the road, then in a mud puddle, covered with snow, then tossed aside as spring comes. The film's crucial scene is a showdown between Sanshiro and his jujitsu rival, Higaki, in a field of tall grasses, swept by wind with rushing clouds overhead; it's a spectacular effect, even if the battle turns out to be a bit anticlimactic. However much the censors may have disliked it, audiences were enthusiastic enough that Kurosawa made a sequel, Sanshiro Sugata Part II in 1942.