|

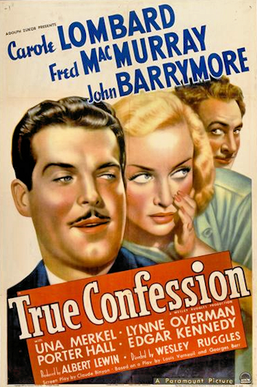

| Clark Gable and Carole Lombard in No Man of Her Own |

If actors weren't cattle, as Alfred Hitchcock is reported to have said, they were at least property, and their studios treated them as such. Clark Gable was becoming one of MGM's most valuable properties when he was loaned out to Paramount to make the only film in which he starred with Carole Lombard, who later became his wife. It was part of a complicated talent swamp initiated by Marion Davies, who had clout with MGM because of her relationship with William Randolph Hearst, who produced films for her that were distributed by MGM. Davies wanted Bing Crosby for a movie, so Paramount traded him to MGM for Gable and No Man of Her Own. Lombard became his co-star only because Miriam Hopkins didn't want to take second billing to Gable. The studio mountains labored to bring forth a cinematic mouse: a passable romantic comedy remembered only for the star teaming. Gable and Lombard are very good in it, though he comes off somewhat better than she does. Lombard was best in movies that gave her license to clown, like Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks, 1934) and My Man Godfrey (Gregory La Cava, 1936). In No Man of Her Own she's simply a woman who knows what she wants, and it isn't necessarily Gable, it's just to get out of the dull little town where she's the librarian. Gable on the other hand is in a role tailor-made for him: "Babe" Stewart, a raffish professional poker player who's as adept at wooing women as he is at cheating at cards. On the verge of getting caught by the detective (J. Farrell MacDonald) who's been tailing him, he skips town and winds up in the burg that Lombard's Connie Randall wants to escape. She catches his eye -- in one pre-Code scene she climbs a ladder and he looks up her skirt -- and with improbable speed they get married. Eventually she finds out that he's not the stockbroker he pretends to be, but nothing fazes her. He gets in trouble again, but just as he's about to take it on the lam, deserting her, he finds of course that he really loves her. The story lacks snap and tension: It was cobbled together from several sources, nominally from a novel by Val Lewton called No Bed of Her Own, a title the Hays Office nixed, but also from another story in Paramount's files. What life the film has comes from Wesley Ruggles's direction and from its performers, including Dorothy Mackaill as Babe's former partner in card-sharping. Lombard and Gable work well together, but reportedly didn't strike any off-screen sparks at the time -- they were both married to other people. They met again at a party four years later and were married in 1939.