Fox News says Fred Phelps’ “God Hates F*gs” hate group is “left wing”

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label religion. Show all posts

Showing posts with label religion. Show all posts

Wednesday, December 26, 2012

Monday, December 24, 2012

Why I Still Celebrate Christmas

I guess if you had to label me anything (though why you'd want to is beyond me), I'm an atheist. But I still love Christmas. That's because it's such a good story, with virgin and manger and star and wise men and shepherds and angels proclaiming peace on Earth. And stories are what we use to make sense of our lives -- as long as we realize that they are stories. If there were holidays celebrating the courtship of Elizabeth and Darcy, or Ahab's pursuit of the white whale, or Frodo's taking the Ring to Mount Doom, I'd celebrate them too.

Stories are always true, because they come from the rich imagining of the human mind. They only become false when people use them to further their own ends, finding ways to warp and distort them into creeds and causes and religions and ideologies. When an ugly old man in the Vatican uses a Christmas address to proclaim his hatred of gay people, or when a TV network promotes closed-mindedness by claiming that those who want to include all believers and non-believers in their celebration of a holiday are somehow waging war on Christmas, then the stories become false.

So whatever you believe, peace be unto you.

Stories are always true, because they come from the rich imagining of the human mind. They only become false when people use them to further their own ends, finding ways to warp and distort them into creeds and causes and religions and ideologies. When an ugly old man in the Vatican uses a Christmas address to proclaim his hatred of gay people, or when a TV network promotes closed-mindedness by claiming that those who want to include all believers and non-believers in their celebration of a holiday are somehow waging war on Christmas, then the stories become false.

So whatever you believe, peace be unto you.

Monday, December 6, 2010

Today's Shamelessness

Think Progress reports on the latest in blatant, unashamed bigotry:

Last month, several Tea Party activists formed a right-wing coalition to oust Rep. Joe Straus (R) as Texas House Speaker. They began circulating emails with anti-Semitic messages against Straus, who is Jewish. The groups ran robo-calls and sent out e-mails demanding a “true Christian leader,” and calling Straus’ opponent, Rep. Ken Paxton (R), “a Christian Conservative who decided not to be pushed around by the Joe Straus thugs.”

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

The Death of Shame

Last night I watched this and was very moved:

Today I read this on Talking Points Memo:

And what I want to know is, when did people lose their sense of shame? At what point did it become acceptable for anyone to make statements like this? Have we become so corrupted by the filth on talk radio that a "favorite of social conservative Republicans" and a professed Christian can write such utterly contemptible stuff?

Doubtless there will be some blowback, and Mr. Fischer will issue one of those "if I offended anybody" non-apologies, but the level of discourse in this country is already damaged beyond repair by crap like this.

Today I read this on Talking Points Memo:

Bryan Fischer, the "Director of Issues Analysis" for the conservative Christian group the American Family Association, was unhappy yesterday that President Obama awarded the Medal of Honor to a soldier for saving lives. This, Fischer wrote on his blog, shows that the Medal of Honor has been "feminized" because "we now award it only for preventing casualties, not for inflicting them."

Here's how the AP described Medal of Honor winner Army Sgt. Salvatore Giunta heroics:

Giunta, the first living Medal of Honor winner of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, braved heavy gunfire to pull a fellow soldier to cover and rescued another who was being dragged away by insurgents.Fischer's take? "So the question is this: when are we going to start awarding the Medal of Honor once again for soldiers who kill people and break things so our families can sleep safely at night?"

"We have feminized the Medal of Honor," Fischer wrote. He also quoted General Patton: "Gen. George Patton once famously said, 'The object of war is not to die for your country but to make the other guy die for his.'" (Actually, Patton doesn't say anything about the other guy: "The object of war is not to die for your country but to make the other bastard die for his.")

Fischer recently argued that it's time to get rid of the "curse" that is the Grizzly Bear because of the number of humans who have been killed by bears: "One human being is worth more than an infinite number of grizzly bears. Another way to put it is that there is no number of live grizzlies worth one dead human being. If it's a choice between grizzlies and humans, the grizzlies have to go. And it's time."

Fischer is a favorite of social conservative Republicans, and spoke at the Values Voter summit this fall alongside Mitt Romney, Jim DeMint, and other big-shot Republicans.

And what I want to know is, when did people lose their sense of shame? At what point did it become acceptable for anyone to make statements like this? Have we become so corrupted by the filth on talk radio that a "favorite of social conservative Republicans" and a professed Christian can write such utterly contemptible stuff?

Doubtless there will be some blowback, and Mr. Fischer will issue one of those "if I offended anybody" non-apologies, but the level of discourse in this country is already damaged beyond repair by crap like this.

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Ignorance Is Bliss

From Leah Garchik's column in today's San Francisco Chronicle:

Home School Day at the Monterey Bay Aquarium allows kids who are educated at home to have the same visiting privileges as kids who visit as part of school groups. Many of the homeschooled are kept away from schools because their parents are fundamentalists. So it's not surprising that on Home School Day on Nov. 8, George Post overheard a docent telling a group, "This fossilized seashell is around 80 million years old," to which one kid responded, "Excuse me, but how is that even possible, since the Earth itself is only 6,000 years old?"Something like that happened to me once, many years ago when I was teaching freshman English in Texas. I had assigned a particularly eloquent passage from Darwin's Origin of Species to an honors class, ready to talk about prose style, when one of them raised her hand to advance the proposition that Darwin's theory had been disproved by the second law of thermodynamics. Naturally, like most English teachers, I had forgotten what the second law of thermodynamics was. (Entropy in closed systems, which organic systems aren't, so the second law doesn't apply.) Unprepared to reply, I gulped, muttered something like "perhaps," and forged ahead with whatever I was prepared to say about sentence structure. I heard her whisper to a friend, "Look how red he's turning."

The aquarium's Ken Peterson says although the aquarium "is a scientific organization," staff members and volunteers do their best to make sure visits are "productive and respectful." That means, he said, that talks to these visitors don't focus on how the Earth came to be but rather how it is now, and the universal obligation to take care of it for future generations. As to creationism versus evolution, "we acknowledge theories exist," but the desired focus, he said, is how "we can all be better stewards."

Post, a photographer, sent some photos of cards homeschooled kids had posted on bulletin boards in the aquarium's learning center. Among them: God "will bring to ruin those who are ruining the earth," a quote from the Bible; "God is grate"; "It's a big hoax you crazy lunatics. Global warming is happening as fast as it was 6,000 years ago."

So Garchik's anecdote leaves me wondering: What was the docent's answer to the question? How do you handle blind ideology "productively and respectfully"? How, in a "scientific organization," is it possible to reply intelligently to anti-scientific thinking? Why would fundamentalist home-schoolers even let their blinkered darlings loose in a place full of scientists?

And isn't there a way we can charge these parents with intellectual child abuse?

Saturday, October 2, 2010

A Refusal to Apologize

Being told that they're sinful and that their love offends God, and being told that their relationships are unworthy of the civil right that is marriage (not the religious rite that some people use to solemnize their civil marriages), can eat away at the souls of gay kids. It makes them feel like they're not valued, that their lives are not worth living. And if one of your children is unlucky enough to be gay, the anti-gay bigotry you espouse makes them doubt that their parents truly love them—to say nothing of the gentle "savior" they've heard so much about, a gentle and loving father who will condemn them to hell for the sin of falling in love with the wrong person.

The children of people who see gay people as sinful or damaged or disordered and unworthy of full civil equality—even if those people strive to express their bigotry in the politest possible way (at least when they happen to be addressing a gay person)—learn to see gay people as sinful, damaged, disordered, and unworthy. And while there may not be any gay adults or couples where you live, or at your church, or at your workplace, I promise you that there are gay and lesbian children in your schools. You may only attack gays and lesbians at the ballot box, nice and impersonally, but your children have the option of attacking actual real gays and lesbians, in person, in real time.

Real gay and lesbian children. Not political abstractions, not "sinners." Real gay and lesbian children.

The dehumanizing bigotries that fall from lips of "faithful Christians," and the lies that spew forth from the pulpit of the churches "faithful Christians" drag their kids to on Sundays, give your straight children a license to verbally abuse, humiliate and condemn the gay children they encounter at school. And many of your straight children—having listened to mom and dad talk about how gay marriage is a threat to the family and how gay sex makes their magic sky friend Jesus cry himself to sleep—feel justified in physically attacking the gay and lesbian children they encounter in their schools. You don't have to explicitly "encourage [your] children to mock, hurt, or intimidate" gay kids. Your encouragement—along with your hatred and fear—is implicit. It's here, it's clear, and we can see the fruits of it.

Friday, June 11, 2010

Questianity

I'm going to start a new religion. All the other ones are too sure of themselves for me. (Well, maybe not the Unitarians or the Buddhists, but there's something too starchy about the former and too detached about the latter.) Its symbol (i.e., its cross or crescent or six-pointed star) will be this:

Its god will be the one Rabelais proposed to meet when he spoke his last words: "I go to seek a Great Perhaps."

Its deadly sins will be the same seven:

Welcome to Questianity, fellow Questioners.

Its god will be the one Rabelais proposed to meet when he spoke his last words: "I go to seek a Great Perhaps."

Its deadly sins will be the same seven:

- Pride: the assumption that one has found the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth

- Envy: the preoccupation with whether what other people believe makes them better off than you are

- Wrath: the willingness to start a fight over beliefs

- Avarice: using a community of belief, like a church, for one's own personal gain (e.g., most politicians)

- Sloth: being too lazy to search and question

- Gluttony: pigging out on the perks of being a true believer (e.g., most politicians)

- Lechery: using the powers of a priesthood for sexual gratification

Welcome to Questianity, fellow Questioners.

Friday, February 12, 2010

What I'm Reading

The Case for God, by Karen Armstrong

This seems to imply that there were no conflicts over myths "until the early modern period." But of course there were. What Alfred North Whitehead called "the fallacy of misplaced concreteness" has always been with us. Ancient peoples believed that their gods and the records of their doings were more than just symbolic representations of "a reality that transcended language," and they were willing to go to war to prove it. The Bible vs. science controversy arises from a belief in the absolute truth of, on the one hand, Scripture, and on the other, scientific method. And each side fears that granting only symbolic status to any part of its ideology undermines the entire ideology and must therefore be fought for.Religious discourse was not intended to be understood literally because it was only possible to speak about a reality that transcended language in symbolic terms. ... The same applies to the creation myth that was central to ancient religion and now has become controversial in the Western world because the Genesis story seems to clash with modern science. But until the early modern period, nobody read a cosmology as a literal account of the origins of life. (p. 15)

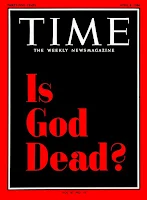

In our own day, the God of the monotheistic tradition has often degenerated into a High God. The rites and practices that once made him a persuasive symbol of the sacred are no longer effective, and people have stopped participating in them. He has therefore become otiosus, an etiolated reality who for all intents and purposes has indeed died or "gone away." (p. 16)Hence the fury over the magazine cover that asked:

Thursday, February 11, 2010

What I'm Reading

The Case for God, by Karen Armstrong

This makes religion sound like yoga or dieting or vowing to read ten pages of Proust every day: one of those worthwhile pastimes that one resolves to take up on New Year's Day, and not the central and most powerful guide to life. But that's okay. It's a definition that I, being something of a spiritual lazybones, rather like.Religion is a practical discipline that teaches us to discover new capabilities of mind and heart. This will be one of the major themes of this book. (p. xiii)

[The] rationalized interpretation of religion has resulted in two distinctively modern phenomena: fundamentalism and atheism. The two are related. (p. xv)And related partly because each is an alarmed reaction to the other.

Yes, and art has gained the upper hand. Sometimes religion's attempts to construct meaning only produce more "relentless pain and injustice." A recognition of this, and of the fact that humans -- not god(s) -- "have created religions," has caused many of us to turn for consolation to the arts and not to religion.If the historians are right about the function of the Lascaux caves, religion and art were inseparable from the very beginning. Like art, religion is an attempt to construct meaning in the face of the relentless pain and injustice of life. As meaning-seeking creatures, men and women fall very easily into despair. They have created religions and works of art to help them find value in their lives, despite all the dispiriting evidence to the contrary. (p. 8)

The desire to cultivate a sense of the transcendent may be the defining human characteristic. (p. 9)Which explains why religions have traditionally been hostile to most of these other outlets.

Human beings are so constituted that periodically they seek out ekstasis, a "stepping outside" of the norm. Today people who no longer find it in a religious setting resort to other outlets: music, dance, art, sex, drugs, or sport. (p. 10)

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

Backward Into Medievalism

Andrew Sullivan on that poll on what Republicans believe:

It has a parallel in the way in which non-violent Islamists have doubled down on medievalism as they feel an overwhelming sense of their own failure to succeed in modernity. There is a profound insecurity and dysfunction in these subcultures which cannot make the transition to modern life and thereby surrender more totally to the ancient past and to hatred of those who succeed. The hatred of Obama - a clearly decent and obviously Christian man - is not about him. It's about them. It's about their resentment of a man who has integrated his own identity and made a place for himself in a pluralist world. They cannot do that - so, like Palin, they invent a world of ancient virtues and moral absolutes that they routinely fail to live up to in reality. I mean: look at Palin's family and Obama's. Whose is the more traditional? And yet Palin is allegedly the avatar of family values - and Obama is a commie subversive.

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

American Taliban

Markos Moulitsas is writing a book called American Taliban, for which he commissioned a poll of people who identify themselves as Republicans. Here are some of its findings:

The poll doesn't even specify what he should be impeached for. Being a Democrat?Should Barack Obama be impeached, or not?Yes 39

No 32

Not Sure 29

Do you think Barack Obama is a socialist?Yes 63

No 21

Not Sure 16

Do you believe Barack Obama was born in the United States, or not?

Yes 42

No 36

Not Sure 22

This one makes my head hurt:

Do you believe Sarah Palin is more qualified to be President than Barack Obama?Yes 53No 14Not Sure 33

These are really nauseating, too:

Should openly gay men and women be allowed to serve in the military?Yes 26No 55Not Sure 19

Should same sex couples be allowed to marry?Yes 7No 77Not Sure 16

Should gay couples receive any state or federal benefits?Yes 11No 68Not Sure 21

Should openly gay men and women be allowed to teach in public schools?Yes 8No 73Not Sure 19

And as for religion:

Should public school students be taught that the book of Genesis in the Bible explains how God created the world?Yes 77No 15Not Sure 8

Do you believe that the only way for an individual to go to heaven is though Jesus Christ, or can one make it to heaven through another faith?Christ 67Other 15Not Sure 18

We're doomed.

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

Stupak-fied

Jeffrey Toobin on abortion and health care reform.

The President is pro-choice, and he has signalled some misgivings about the Stupak amendment. But, like many modern pro-choice Democrats, he has worked so hard to be respectful of his opponents on this issue that he sometimes seems to cede them the moral high ground. In his book “The Audacity of Hope,” he describes the “undeniably difficult issue of abortion” and ponders “the middle-aged feminist who still mourns her abortion.” Elsewhere, he announces, “Abortion vexes.” The opponents of abortion aren’t vexed—they are mobilized, focussed, and driven to succeed. The Catholic bishops took the lead in pushing for the Stupak amendment, and they squeezed legislators in a way that would do any K Street lobbyist proud. (One never sees that kind of effort on behalf of other aspects of Catholic teaching, like opposition to the death penalty.) Meanwhile, the pro-choice forces temporized. But, as Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg observed not long ago, abortion rights “center on a woman’s autonomy to determine her life’s course, and thus to enjoy equal citizenship stature.” Every diminishment of that right diminishes women. With stakes of such magnitude, it is wise to weigh carefully the difference between compromise and surrender.

Scare Tactics

This sort of thing scares the hell out of me.

Visit msnbc.com for Breaking News, World News, and News about the Economy

Sunday, October 25, 2009

Thursday, October 8, 2009

What I'm Reading

Notes on The Evolution of God, by Robert Wright, Part V: God Goes Global (Or Doesn't)

Notes on The Evolution of God, by Robert Wright, Part V: God Goes Global (Or Doesn't) A group of conservatives recently announced their plans to translate (read: edit) the Bible and thereby eliminate the liberalism that modern translators have allegedly introduced. This latest salvo in the ideological warfare of our times only made me appreciate the more how bold Robert Wright has been in approaching the eternally volatile subject of religion.

Having surveyed early polytheistic religions and the three Abrahamic faiths -- Judaism, Christianity, and Islam -- he turns his attention in the last section (plus an Afterword and an Appendix) to the future. Specifically, he's concerned with the development of what he calls "the moral imagination" in an age of globalization, in which the various religions are often engaged in hostilities with one another. He's writing here primarily about Christianity and Islam, of course, the current headline-makers in the United States, and I think his argument suffers a little by not focusing more on the conflict between Judaism and Islam, and by ignoring completely the bloody conflict of Muslims and Hindus on the Indian subcontinent. But perhaps that's material for another book.

"As we've seen," he writes, "successful religions have always tended to salvation at the social level, encouraging behaviors that bring order." For example, Paul's enumeration of sins includes such behaviors as adultery, promiscuity, jealousy, and anger -- all behaviors that are in some sense anti-social. "But now religion seems to be the problem, not the solution."

Wright sees "moral evolution" in terms of game theory: One of his earlier books was Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny, in which he argues that, historically, cultures that chose to strive for win-win ("non-zero-sum") outcomes have been more successful than those that chose to work for "zero-sum" -- win-lose -- results. This argument has been present throughout his discussion of the evolution of religions, though I've previously chosen not to present it in his terms because his overuse of "zero-sum" and "non-zero-sum" struck me as verging on jargon; his argument is clear enough without them.

This is the way moral evolution happens -- in ancient Israel, in the Rome of early Christianity, in Muhammad's Arabia, in the modern world: a people's culture adapts to salient shifts in game-theoretical dynamics by changing its evaluation of the moral status of the people it is playing the game with. If the culture is a religious one, this adaptation will involve changes in the way scriptures are interpreted and in the choice of which scriptures to highlight. It happened in ancient times, and it happens now.

Consider the conservatives' attempt to "translate" the Bible to exclude liberals from their circle of salvation. Unfortunately, this is a zero-sum approach, the reverse of the approach of religions that strove for greater inclusiveness and tolerance, and thereby succeeded and thrived. And of course, "the relationship between some Muslims and the West is zero-sum. Terrorist leaders have aims that are at odds with the welfare of westerners. The West's goal is to hurt their cause, to deprive them of new recruits and of political support." For the West, as Wright sees it, the solution is to convert to a "non-zero-sum dynamic" -- to try to alleviate the discontent of Muslims as a whole, to show respect and to make them aware of the benefits of involvement with the West, thereby cutting off the source of the discontent that nourishes terrorism.

The problem is "that our mental equipment for dealing with game-theoretical dynamics was designed for a hunter-gatherer environment, not for the modern world." We instinctively distrust that which is different, that which is not-like-us. And this often blocks "our 'moral imagination,' our capacity to put ourselves in the shoes of another person."

Indeed, the moral imagination is one of the main drivers of the pattern we've seen throughout the book: the tendency to find tolerance in religion when the people in question are people you can do business with and to find intolerance or even belligerence when you perceive the relationship to be instead zero-sum."The book has traced the widening circles of the moral imagination from encompassing family, then tribe, then state, then international relationships. And now, faced with global problems like climate change and nuclear proliferation, the circle has to widen to encompass the whole planet. "Technology has made the planet too small, too finely interdependent, for enmity between large blocs to be in their enduring interest."

This is the next stage in the evolution of religion, of god: "[T]raditionally, religions that have failed to align individual salvation with social salvation have not, in the end, fared well. And, like it or not, the social system to be saved is now a global one." Conscious that many people no longer believe in the afterlife, the salvation that religions have held out as a reward for good behavior in this life, Wright provides a secular definition of "salvation" from its Latin roots, "meaning to stay intact, to remain whole, to be in good health. And everyone, atheist, agnostic, and believer alike, is trying to stay in good mental health, to keep their psyche or spirit (or whatever they call it) intact, to keep body and soul together."

So the basic challenge of linking individual salvation to social salvation can be stated in equally symmetrical yet more secular language: the challenge is to link the avoidance of individual chaos to the avoidance of social chaos. Or: link the pursuit of psychic intactness to social intactness. Or: link the pursuit of personal integrity to social integrity. Or: link the pursuit of psychic harmony to social harmony.

Can this be accomplished without religion, without belief in a personal god? That it can be is the crux of Wright's argument. God, he posits, is essentially unknowable. He likens god to the electron, the existence of which scientists deduce pragmatically: "Granted, we believe in the existence of the electron even though our attempts thus far to conceive of it have been imperfect at best. Still, there's a sense in which our imperfect conceptions of the electron have worked. We manipulate physical reality on the assumption that electrons exist as we imperfectly conceive them and -- voilà -- we get the personal computer." Similarly, Wright posits the existence of "a moral order, linkage between the growth of social organization and progress toward moral truth." He sees the evolutionary process as moving in this direction, and deduces something that created the process.

The best we can do within the intellectual framework of this book is to posit the existence of God in a very abstract sense and defend belief in a more personal god in pragmatic terms -- as being true in the sense that some other bedrock beliefs, including some scientific ones, are true.

This may or may not come as comfort or consolation for those who cling to a traditional belief, especially those who turn to religion for solace in times of crisis. It certainly doesn't go very far to assuage my agnosticism, either. As Wright admits, "as divinity is defined more abstractly to fit more comfortably into a scientific worldview, God becomes harder to relate to." No kidding.

Sunday, October 4, 2009

What I'm Reading

Notes on The Evolution of God, by Robert Wright, Part IV: The Triumph of Islam

Notes on The Evolution of God, by Robert Wright, Part IV: The Triumph of IslamThose of us raised in the Judeo-Christian tradition are always going to have problems comprehending Islam, in part because its foundation in the Abrahamic beliefs and traditions puts it so near to us, while its rejection of some of the key dogmas of Judaism and Christianity puts it so far away. And, truth be told, the essence of Islam, the Koran, is so difficult for us to approach. It is, as Wright says, "unlike the religious text westerners are most familiar with, the Bible. For one thing, it is more monotonous.... The Bible came from dozens of different authors working over a millennium, if not more. The Koran came from (or through, Muslims would say) one man in the course of two decades.

Suppose, Wright says, "the whole Bible had been written by Jesus." By which he means the "historical" Jesus -- "the Jesus who, so far as we can tell, was ... a fire-and-brimstone preacher who warned his people that Judgment Day was coming and that many of them were a long way from meriting favorable judgment.... [T]his book would have the flavor of the Koran. Jesus and Muhammad probably had a lot in common." The Koran "shifts in tone, from tolerance and forbearance to intolerance and belligerence and back," Wright says. And this reflects the changing circumstances in Muhammad's life. "By the time of his death, Muhammad had gone from being a monotheistic prophet, preaching in the largely polytheistic city of Mecca, to being the head of an Islamic state with expansionist tendencies." And as Wright has shown in writing about Judaism and Christianity, theology and morality "are ultimately obedient to the facts on the ground."

From the standpoint of high-status Meccan polytheists, if there was one thing worse than someone who denounced the wealthy and preached monotheism, it was someone who did the two synergistically. That was Muhammad. Like Jesus, he was intensely apocalyptic in a left-wing way; he believed that Judgment Day would bring a radical inversion of fortunes. Jesus had said that no rich man would enter the kingdom of heaven. The Koran says that "Whoso chooseth the harvest field of this life" will indeed prosper; "but no portion shall there be for him in the life to come."

We're also so used to referring to Muhammad's god as Allah, that we sometimes forget that Allah is the same god as the one worshiped by Jews and Christians: "Muhammad's basic claim was that he was a prophet sent by the god who had first revealed himself to Abraham and later had spoken through Moses and Jesus." So Wright chooses to refer to Allah as "God" in his discussions of Islam. Moreover, there is some evidence that Allah was the Judeo-Christian God, who had been "accepted into the [pre-Islamic] Meccan pantheon some time earlier to cement relations with Christian trading partners from Syria, or maybe brought to Arabia by Christian or Jewish migrants.... This explains the rhetorical thrust of the Koran -- not to convince Meccans to believe that Allah exists or that he is the creator God, but to convince them that he is the only God worthy of devotion, indeed the only God in existence."

Of course, in the post-9/11 world, what bothers us most is the question of tolerance versus belligerence, the problem of the Koran's attitude toward "infidels." Here again, Wright sees the inconsistencies in the Koran as reflective of "the facts on the ground." "At one point Muhammad is urging Muslims to kill infidels and at another moment he is a beacon of religious tolerance. The two Muhammads seem irreconcilable at first, but they are just one man, adapting to circumstance." In his years in Mecca, which produced most of the writings in the Koran, Muhammad often counseled his followers to be patient and "resist the impulse of vengeance."

When you encounter infidels, says one sura, "Turn thou from them, and say 'Peace:'" Let God handle the rest: "In the end they shall know their folly." Another Meccan sura suggests how to handle a confrontation with a confirmed infidel. Just say: "I shall never worship that which ye worship. Neither will ye worship that which I worship. To you be your religion; to me my religion." ... This theme is constant through Muhammad's days in Mecca. In what is considered one of the earliest Meccan suras, God says to Muhammad: "Endure what they say with patience, and depart from them with a decorous departure."As Wright says, this is entirely consistent with Paul's admonitions to bless one's persecutors and the Hebrew Bible's advice to the Israelites, when they were on the losing side, to practice tolerance of non-believers. "After moving to Medina and mobilizing its resources, Muhammad would, like the Israelites of Deuteronomy, find war a more auspicious prospect.... But so long as Muhammad remained in Mecca, fighting was unappealing and religious tolerance expansive."

Wright sees "the difference between Muhammad in Mecca and Muhammad in Medina" as "the difference between a prophet and a politician." As his political success grew, he tried reaching out to Jews and Christians: "the Jewish ban on eating pork was mirrored in a Muslim ban on eating pork, probably first enunciated in Medina." And he accepted the Christian belief in the virgin birth, although he drew the line at Jesus's divinity, believing it was a step toward polytheism. On the other hand, he wanted Jews and Christians "to accept that their own scriptures, however sacred, had been a prelude to the Koran; that their own prophets, however great, had been preludes to himself. Any merger of religions he may have envisioned wasn't a merger of equals." And that would be too much to ask.

And so the Koran is, like the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, filled with ambiguities, with the result that "Even today, some Muslims like to emphasize [Muhammad's] belligerence -- they wage holy war and say they do so in the finest tradition of the Prophet -- while other Muslims insist that Islam is a religion of peace, in the finest tradition of the Prophet." Today, much interpretation of the Koran centers on the word jihad, which means "striving" or "struggle," but actually appears in the Koran only four times. "And depending on which of those four verses you pick, you could make the case that jihad is either about an internal struggle toward spiritual discipline or about war; there is no 'doctrine' of jihad in the Koran.... If the Koran were a manual for all-out jihad, it would deem unbelief by itself sufficient cause for attack. It doesn't."

Muhammad pursued an expansionist foreign policy, and war was a key instrument. But to successfully pursue such a policy -- and he was certainly successful -- you have to take a nuanced approach to warfare. You can't use it gratuitously, when its costs exceed its benefits. And you can't reject potentially helpful allies just because they don't share your religion.... Indeed, if the standard versions of Muslim history are correct, he was forging alliances with non-Muslim Arabian tribes until the day he died. Once you see Muhammad in this light -- as a political leader who deftly launched an empire -- the parts of the Koran that bear on war make perfect sense. They are just Imperialism 101.Wright observes that Muhammad took on, at various times in his career, the character of many of his "Abrahamic predecessors." In Mecca, where he was the leader of "a small band of devotees, warning that Judgment Day was coming," he resembled Jesus. Like Isaiah, he prophesied that his persecutors would suffer the wrath of God. Like Moses, he led his followers to the promised land: Medina. Like Paul, he proselytized among the Jews. And when he gained power, "he started to resemble King Josiah, the man who put the ancient Israelites on the path toward monotheism in the course of gathering power."

To be sure, Josiah's moral compass seems to have been more thoroughly skewed by his ambitions than Muhammad's. The prescription in Deuteronomy for neighboring infidel cities is all-out genocide -- kill all men, women, and children, not to mention livestock. There is nothing in the Koran that compares with this, arguably the moral low point of Abrahamic scripture. Still, if Muhammad never countenanced the killing of women and children, he did countenance a lot of killing.

In some regards, the Koran is more generous than the Bible when it comes to salvation. It "says more than once that not just Muslims but Jews and Christians are eligible for salvation so long as they believe in God and in Judgment Day and live a life worthy of favorable judgment." On the other hand, the Bible is a more cosmopolitan work than the Koran. The Hebrew Bible and the New Testament "captured ideas of great civilizations, from Mesopotamia to Egypt to Christianity's Hellenistic milieu. The Koran took shape in two desert towns on the margin of empires, uttered by a man who was more a doer than a thinker and was probably illiterate." Still, Wright sees Muhammad as "a more modern figure than Moses and Jesus." He had "no special powers. He can't turn a rod into a snake or water into wine.... [T]he Koranic Muhammad, unlike the biblical Jesus and Moses, doesn't depend on miracle-working for proof of proximity to God."

And the question remains about whether the teachings of any of the Abrahamic religions remain relevant to the circumstances of our century. This is where Wright is headed next: to a discussion of "the effect of changing circumstance" -- the facts on the ground -- "on human moral consciousness." The Koran, Wright observes, oscillates from "To you your religion; to me my religion" to "Kill the polytheists wherever you find them." "All of the Abrahamic scriptures attest to the correlation between circumstance and moral consciousness, but none so richly as the Koran. In that sense, at least, the Koran is unrivaled as a revelation."

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

What I'm Reading

Notes on The Evolution of God, by Robert Wright, Part III: The Invention of Christianity

Notes on The Evolution of God, by Robert Wright, Part III: The Invention of Christianity These days, proclaiming oneself a Christian can put you in the company of political belligerents, right-wingers and ideologues. Which may be one reason I now choose to call myself an agnostic rather than what my upbringing suggests: a conflicted Christian. But reading Wright's account of the origins of Christianity does reinforce my sense of alienation from the religion in which I was raised.

For one thing, Wright's depiction of the "historical Jesus" is somewhat unsettling: He comes across as anything but the Sunday School "gentle Jesus, meek and mild," or even the appealing, if austere, moral philosopher that I fancied him as in my maturity. If, as Wright does, we take the gospel of Mark as "the most factually reliable of the four gospels" because it's the earliest in composition and hence closest to the time in which Jesus lived, he "sounds rather like other healers and exorcists who roamed Palestine at the time" and "like a classic shaman in a 'primitive' society." Moreover, "the earliest renderings of his message will disappoint Christians who credit Jesus with bringing the good news of God's boundless compassion."

In short, if we are to judge by Mark, the earliest and most reliable of the four gospels, the Jesus we know today isn't the Jesus who really existed. The real Jesus believes you should love your neighbors, but that isn't to be confused with loving all mankind. He believes you should love God, but there's no mention of God loving you. In fact, if you don't repent of your sins and heed Jesus's message, you will be denied entry into the kingdom of God.... In Mark there is no Sermon on the Mount, no beatitudes. Jesus doesn't say, "Blessed are the meek" or "Turn the other cheek" or "Love your enemy."To be sure, there exists the possibility that what's missing from Mark -- including the Sermon on the Mount -- may have been recorded in another document, known as "Q," that was a source for Matthew and Luke, "and some scholars think it was much earlier, bearing at least as close a connecton to the 'historical Jesus' as Mark does." But in Wright's view of things, what Jesus actually said is less important than what Paul made of his words and his life. "[M]ore than Jesus, apparently, Paul was responsible for injecting [Christianity] with the notion of interethnic brotherly love."

In the Roman Empire, the century after the Crucifixion was a time of dislocation. People streamed into cities from farms and small towns, encountered alien cultures and peoples, and often faced this flux without the support of kin.... The Christian church was offering the spirit of kinship that people needed.... In that letter to the Corinthians that is featured at so many weddings, Paul used the appellation "brothers" more than twenty times.Wright sees Paul as an entrepreneur, "who wanted to extend the brand, the Jesus brand; he wanted to set up franchises -- congregations of Jesus followers -- in cities across the Roman Empire." As the CEO of Christianity, he used the only "information technology" he had at hand, the epistles, "to keep church leaders in line." And the "brotherly love" that he promoted in his letters was a way of making "churches attractive places to be" and also "a tool Paul could use at a distance to induce congregational cohesion."

Another means to attracting followers among the Gentiles was to rid the church of some of the harsher aspects of Jewish Law, such as circumcision:

In the days before modern anesthesia, requiring grown men to have penis surgery in order to join a religion fell under the rubric "disincentive." Paul grasped the importance of such barriers to entry. So far as Gentiles were concerned, he jettisoned most of the Jewish dietary code and, with special emphasis, the circumcision mandate.Still, "Paul may have considered himself a good, Torah-abiding Jew, albeit one who, in contrast to most other Jews, was convinced that the Jewish messiah had finally arrived. (In none of his letters does Paul use the word 'Christian.')"

Paul also went out of his way to recruit converts from among the well-to-do. "Though Christianity is famous for welcoming the poor and powerless into its congregations, to actually run the congregations Paul needed people of higher social position." Wright notes that the early convert mentioned in Acts, Lydia, was "a dealer in purple cloth," which was "a pricey fabric, made with a rare dye. Her clientele was wealthy, and she had the resources to have traveled to Macedonia from her home in Asia Minor. She was the ancient equivalent of someone who today makes a transatlantic or transpacific flight in business class." And one of the perks of becoming a Christian was that the churches offered hospitality -- lodging, advice, "connections," etc. -- to other Christian travelers.

Paul's international church built on existing cosmopolitan values of interethnic tolerance and amity, but in offering its international networking services to people of means, it went beyond those values; a kind of interethnic love was the core value that held the system together.But we haven't quite got to the concept of universal love yet. "If you were outside the circle of proper belief, Christians didn't really love you -- at least, they didn't love you the way they loved other Christians.... Even the people who had introduced this God to the world, the Jews, didn't qualify for the kingdom of heaven unless they abandoned Judaism."

Paul's organizational skills wouldn't have been enough to allow Christianity to survive if he hadn't had a product to sell. That product was salvation: "The heart of the Christian message is that God sent his son to lay out the path to eternal life." The odd thing is that this notion of "Jesus as heavenly arbiter of immortality ... would have seemed strange to followers of Jesus during his lifetime." The whole question of heaven, of the kingdom of God, grew more complicated when it became more apparent that the kingdom Jesus preached was not going to arrive in the lifetimes of the first believers.

Wright points out, "In the gospels, Jesus doesn't say he'll return." He refers instead to prophesies in the Hebrew Bible of "a 'Son of Man' ... who will descend from the skies at the climax of history." It took much ingenious reasoning on the part of early Christians to interpret this as Jesus referring to himself. But it "may have been crucial in the eventual triumph of Christianity.... The postmortem identification of Jesus with the Son of Man was a key evolutionary adaptation." Wright notes, "It is more than a decade after Paul's ministry before Christian literature clearly refers to immediate reward for the good in the afterlife.... Had Christian doctrine not made this turn, it would have lost credibility as the kingdom of God failed to show up on earth -- as generations and generations of Christians were seen to have died without getting their reward."

Of course, the concept of immortal life was not unique to Christianity, so what the young religion also needed to do was provide what other religions also did: "not just a heavenly expectation, but an earthly experience: a dramatic sense of release," a lifting of people's "burdensome sense of their moral imperfection -- the sense of sin." One of Paul's contributions to the selling of Christianity was to define sin "so that the avoidance of it sustains the cohesion and growth of the church." So in the epistle to the Galatians, Paul provides a list of sins, of which only two "-- idolatry and sorcery -- are about theology. The rest are about workaday social cohesion" -- things like adultery, promiscuity, drunkenness, jealousy, envy, anger. Avoiding these sins "makes a blissful afterlife contingent on your moral fiber -- a fiber that, in turn, gives sinew to the church itself."

In the end, the arrival of Christianity also signified a next step in the evolution of god -- the concept of the deity as "protective, consoling, and, if demanding, at least able to forgive." But he cautions against attributing this concept entirely to Christianity. It arose in part because of the development of civilization, which "defused old sources of insecurity" such as attacks from wild animals or the need to hunt for one's daily sustenance, but also created new psychological insecurities.

Christians worship a loving father God, and many of them think this god is distinctively Christian: whereas the God of the Old Testament features an austere, even vengeful, father, the God of the New Testament -- the God revealed by Christianity -- is a kind and forgiving father. This view is too simple, and not only because a god who is kind and merciful shows up repeatedly in the Hebrew Bible, but because such gods had shown up long before the Hebrew Bible was written.... Any religion that grew as fast as Christianity did must have been meeting common human needs, and it's unlikely that common human needs would have gone unmet by all earlier religions.

Christianity was the outgrowth of a particular social system, but that system has radically changed. "When Christianity reigned in Rome, and, later, when Islam was at the height of its geopolitical influence, the scope of these religions roughly coincided with the scope of whole civilizations." But now the world "is so interconnected and interdependent that Christianity and Islam, like it or not, inhabit a single social system -- the planet."

So when Christians, in pursuing Christian salvation, and Muslims, in pursuing Muslim salvation, help keep their religions intact, they're not necessarily keeping the social system they inhabit intact. Indeed, they sometimes seem to be doing the opposite.

Sunday, September 27, 2009

What I'm Reading

Notes on The Evolution of God, by Robert Wright, Part II: The Emergence of Abrahamic Monotheism

Notes on The Evolution of God, by Robert Wright, Part II: The Emergence of Abrahamic Monotheism When I was a sophomore in college, I was in an honors seminar in which we discussed the Big Ideas of Western civilization. One week, the professor asked us, "Why do we think monotheism is superior to polytheism?" I remember that the discussion fizzled, perhaps because we were in the Bible Belt, where most of us were raised to think that the existence of one and only one god was revealed truth. I was open to the question, but I don't think I came up with an answer, other than that maybe we prefer unity to diversity. Which of course elicited only another "why" from the professor.

It has occurred to me since then that many nominally monotheistic believers have polytheistic tendencies. After all, surveys show that an awful lot of people believe in angels who are more than just God's messengers, but also do things like push people out of the way of oncoming buses and such. And then there's the widespread belief in the existence of Satan, which suggests that a lot of people are Manichaeans without knowing it. And there's also the Trinity, which seems to me a needless multiplication of entities that should have been lopped off by Occam's razor.

I guess it shouldn't come as a surprise, then, that according to Robert Wright's reading of it, the Bible -- at least the Old Testament -- is kind of confusing on this monotheism thing. "If you read the Hebrew Bible carefully, it tells the story of a god in evolution, a god whose character changes radically from beginning to end." It not only starts with the "hands-on deity" whom Adam and Eve hear walking in the garden, but also with a god who seems to belong to an entourage of deities: "It talks more than once about a 'divine council' in which God takes a seat; and the other seats don't seem to be occupied by angels." It concludes with a god who is omnipotent, omniscient, solitary and surprisingly detached from the affairs of humankind -- "indeed there is no mention of him at all in the last book of the Hebrew Bible, Esther." In short, "Israelite religion reached monotheism only after a period of 'monolatry' -- exclusive devotion to one god without denying the existence of others."

Wright also tells us, "It's even possible that Yahweh, who spends so much of the Bible fighting against those nasty Canaanite gods for the allegiance of Israelites, actually started life as a Canaanite god, not an import." He cites evidence that the northern Canaanite god named El may have been a precursor of Yahweh, "that Yahweh in some way emerged from El, and may even have started life as a renamed version of El." Wright notes that in Part I, he has already established that "the ancient world was full of politically expedient theological fusions." In this case, Yahweh "rose through the ranks" because of "a shift in the relative power of northern and southern Israel, of El's heartland and Yahweh's heartland." And "whatever the truth about Yahweh's early history, there is one thing we can say with some confidence: the Bible's editors and translators have sometimes obscured it -- perhaps deliberately, in an attempt to conceal evidence of early mainstream polytheism."

But Yahweh seems to have emerged not only from El, but also from that more notorious Canaanite deity, Baal. Some passages in the Bible, including even the parting of the Red Sea, seem to have curious parallels to myths attributed to Baal.

One initially puzzling aspect of the situation is that Baal, throughout the Bible, is Yahweh's rival. Bitter enmity doesn't seem like a good basis for merger. But, actually, in cultural evolution, competition can indeed spur convergence. Certainly that's true in modern cultural evolution. The reason operating systems made by Microsoft and Apple are so similar is that the two companies borrow (that's the polite term) features pioneered by the other when they prove popular. So too with religions.In the Bible, "Yahweh beats Baal in the showdown arranged by Elijah, and then later 'appears' to Elijah -- invisibly, ineffably -- on Mount Sinai. ... a milestone in the evolution of monolatry, a way station on the road to full-fledged monotheism." Wright observes that the first Commandment -- "You shall have no other gods before me" -- is a "monolatrous verse often read as monotheistic."

Wright puts the rejection of "foreign" gods, the solidifying of the Israelites' belief into a single god, Yahweh, in the context of the times:

This ancient sociopolitical environment is a lot like the modern sociopolitical environment as shaped by globalization. Then as now international trade and attendant economic advance had brought sharp social change and sharp social cleavages, delimiting affluent cosmopolitans from poorer and more insular people. Then as now some of those in the latter category were ambivalent, at best, about foreign influence, economic and cultural, and were correspondingly resentful of the cosmopolitan elites who fed on it. And, then as now, some of those in the latter category extended their dislike of the foreign to theology, growing cold toward religious traditions that signified the alien. This dynamic has to varying degrees helped produce fundamentalist Christians, fundamentalist Jews, and fundamentalist Muslims. And apparently it helped produce the god they worship.

Another reason for Yahweh's emergence was that he had always been a god of battles, "the god who could authorize war and guide his people through it ...; he was the commander-in-chief god. So Yahweh would naturally draw popular allegiance from international turmoil." So when Josiah became king around 640 BCE, he destroyed the temples of other gods. "Josiah's reign marked a watershed in the movement toward monotheism. Yahweh and Yahweh alone ... was now the officially sanctioned god of Israelites."

But calamity was about to befall them: the Babylonian exile. And the interesting thing is that this great national catastrophe only made Yahweh stronger. "To think of your god as losing so abjectly was almost to think of your god as dead. And in those days, in that part of the world, thinking of your national god as dead meant thinking of your nationality as dead." So the conclusion was that "the outcome had been Yahweh's will." He must be punishing us for our sins by letting something so awful happen to us, went the reasoning, and "any god that wields a whole empire as an instrument of reprimand must be pretty potent." Maybe even ... omnipotent?

An apt response when a people kills your god is to kill theirs -- to define it out of existence. And if other nations' gods no longer exist, and if you've already decided (back in Josiah's time) that Yahweh is the only god in your nation, then you've just segued from monolatry to monotheism.... Monotheism was, among other things, the ultimate revenge.

Meanwhile, as the Israelites were turning to monotheism as a way of explaining what had happened to them, the Greeks were finding their own path to monotheism through scientific inquiry. "The more nature was seen as logical -- the more its surface irregularities dissolved into regular law -- the more sense it made to concentrate divinity into a single impetus that lay somewhere behind it all." Which in turn inspired a Jewish thinker living in Alexandria, Philo. "Ethnically and religiously he was a Jew. Politically, he lived in the Roman Empire. Intellectually and socially, his world was heavily Greek." Philo's cosmopolitanism gave him an appreciation for what we would now call diversity, and it made him value tolerance in particular.

Tolerance, in fact, was emerging in post-exilic Jewish thought, as evidenced in the books of Ruth and Jonah. The latter happens to be one of my favorite books in the Bible, mainly because it's perhaps the funniest. Not just the whale stuff, but the character of Jonah himself, so put-upon by God's insistence that he go and cry out against Nineveh, and then so ticked off when God changes his mind and decides not to destroy the city after all. God gets one of the great punchlines when he replies to Jonah's pique: "And should not I spare Nineveh, that great city, wherein are more than sixscore thousand persons that cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand; and also much cattle."

As Wright puts it, "Traditionally, this sort of ignorance -- not knowing good from evil -- is what had stirred God's wrath, not his compassion.... In the book of Ezekiel, God was proud of having made Assyria suffer 'as its wickedness deserves.' Now, in Jonah, the suffering of Assyrians gives God no pleasure, and their wickedness he sees as lamentable confusion. This is a god capable of radical growth." (And that aside about the cattle is a hoot.)

God's growth is what gives Wright hope for the world's religions: "when I say God shows moral progress, what I'm really saying is that people's conception of god moves in a morally progressive direction." Which provokes this question:

[I]f the human conception of god features moral growth, and if this refelcts corresponding moral growth on the part of humanity itself, and if humanity's moral growth flows from basic dynamics underlying history, and if we conclude that this growth is therefore evidence of 'higher purpose,' does this amount to evidence of an actual god?For the moment at least, the question remains rhetorical as Wright returns to Philo of Alexandria and another problem that plagues people of faith: the conflict of science and religion. In Philo's case, it was one of "cognitive dissonance. Philo believed that all of Judaism and large parts of Greek philosophy were true, and so long as they seemed at odds, he couldn't rest easy." So "[w]hile Jesus was preaching in Galilee, Philo, over in Alexandria, was laying out a world-view with key ingredients, and specific terminology, that would show up in Christianity as it solidified over the next two centuries."

One way that Philo went about reconciling Greek science and Jewish religion was to treat much of the latter as allegorical and symbolic -- an anticipation of what most non-fundamentalist believers have had to do. And to explain God's role in the world, he used the term "logos," which meant "word" and "speech" and "account" and "computation" and "reason" and "order." "In his mission to reconcile a transcendent God with an active and meaningful God, Philo would draw on all these meanings, and more." Wright compares Philo to a computer programmer or a video game designer.

Long before modern science started clashing with the six-day creation scenario in Genesis, Philo had preempted the conflict by calling those six days allegorical: they actually referred not to God's creation of the earth and animals and people, but to his creation of the Logos, the divine algorithm, which would bring earth and animals and people into existence once it was unleashed in the material world. ... God himself is beyond the material universe, somewhat the way a video game designer is outside of the video game. Yet the video game itself -- the algorithm inside the box -- is an extension of the designer, a reflection of the designer's mind.

But the video game analogy is inadequate, Wright notes: "However transcendent God is, we can get closer to actual contact with him than Pac-Man could ever have gotten to Toru Iwatani, Pac-Man's creator."

[T]he Logos is a little like the Buddhist concept of dharma: it is both the truth about the way things are -- about how the universe works -- and the truth about the way we should live our lives given the way things are. It is the law of nature and it is the law for living in light of nature. This double entendre is hard for some people to accept, as today we often separate description (scientific laws) from prescription (moral laws). But to many ancient thinkers the connection was intimate: if basic laws of nature were laid down by a perfect God, then we should behave in accordance with them, aid in their realization; we should help the Logos move humanity in the direction God wants humanity to move in.

Of course, we've heard about the Logos elsewhere, in the beginning of the book of John. But that's the next section of the book.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

What I'm Reading

Notes on The Evolution of God, by Robert Wright, Part I: The Birth and Growth of Gods

Notes on The Evolution of God, by Robert Wright, Part I: The Birth and Growth of GodsI was raised Methodist, which in my small Southern town was a little lower than the angels -- i.e., the Episcopalians. We could pride ourselves on not being Baptists, but were uncertain where we stood with regard to the Presbyterians. (We had a suspicion they were higher on the social scale, but maybe not much.) I remained Methodist through college, but all it did was make me priggish, conflicted, and sexually timid.

When I left home, I met Catholics and Jews (and sometimes a few Protestants) whose faith was real and profound, integral to their existence in ways that my own had never been. But I knew I could never be like them; I lacked something, perhaps the cultural roots that nourished these friends. My own roots were in the sandy loam of Mississippi and easily dislodged, and in graduate school I flirted with Episcopalianism, thinking that I might find my roots there -- after all, I was an English major. But I gave it up once the novelty wore off of attending services in a church that George and Martha Washington once worshiped in and where Teddy Roosevelt once taught Sunday school.

My drift away from religion had begun. Occasionally, like the woman in Wallace Stevens' "Sunday Morning," "I still feel / The need of some imperishable bliss." But the tug toward belief grows fainter as I'm borne along toward my three-score-and-tenth year. There are few questions that religion can answer for me that aren't answered by science, few moral problems that can't be settled for me by law and custom, few insights into humankind that aren't supplied to me by literature and art. Sometimes I feel something listening to religious music -- Bach chorales, Handel's "Messiah," the Verdi Requiem, Brahms' "Deutsches Requiem," the soprano's ecstatic outburst of "Christe" in Mozart's C minor Mass, even the old hymns I used to sing in church -- but the experience is aesthetic, not qualitatively different from what I experience listening to great secular music. Or else it's nostalgia, a sentimental regret for losing something I once thought I had. True, I have prayed at times of stress, but if my words flew up, my thoughts remained below. What comfort I received was in focusing and thereby calming my thoughts, and if I heard a replying voice it was my own.

I can't go all the way to atheism, however. Maybe the immensity of the observable universe suggests that there must be a point to something so vast, so strange, so not me. And so I call myself agnostic for want of a better label. The realization that others find something -- meaning? truth? help? -- in religion leads me to try to understand what it is, which is why I find myself reading books about it.

Like this one. Robert Wright's premise that religious beliefs undergo a process of natural selection, that the ones most useful in helping their believers survive are the beliefs that prevail, would have gotten him burned at the stake at one time. (And still might in parts of Oklahoma and Texas.) But it fits with what I know of history. He asserts that "religion has been deeply shaped by many factors, ranging from politics to economics to the human emotional infrastructure.

Evolutionary psychology has shown that, bizarre as some "primitive" beliefs may sound -- and bizarre as some "modern" religious beliefs may sound to atheists and agnostics -- they are natural outgrowths of humanity, natural products of a brain built by natural selection to make sense of the world with a hodgepodge of tools whose collective output isn't wholly rational.

He begins in prehistory, with the gods of the hunter-gatherers -- a difficult place to start because we know so little about these societies. What we do know is that unlike Jews, Christians, or Muslims, their belief systems weren't "constrained from the outset by a stiff premise: that reality is governed by an all-knowing, all-powerful and good God." And that, "in hunter-gatherer societies, gods by and large don't help solve moral problems that would exist in their absence."

Even if religion is largely about morality today, it doesn't seem to have started out that way. And certainly most hunter-gatherer societies don't deploy the ultimate moral incentive, a heaven reserved for the good and a hell to house the bad. ... There is always an afterlife in hunter-gatherer religion, but it is almost never a carrot or a stick. Often everyone's spirit winds up in the same eternal home.Their religions also weren't about maintaining social order, because their societies were so small and the threats to them so great that social cohesion was necessary for survival. What hunter-gatherer religions do have in common with the contemporary religions of the world is that "they try to explain why bad things happen, and they thus offer a way to make things better."

These societies also had people who discovered that they could gain power by figuring out what the gods wanted: "Once there was belief in the supernatural, there was a demand for people who claimed to fathom it. ... The shaman is the first step toward an archbishop or an ayatollah." This leads Wright into some very interesting (one might say trippy) speculations on the genuineness of the transcendental experiences claimed by shamans.

No doubt the world's shamans have run the gamut from true believer to calculating fraud.... In any event, there is little doubt that many shamans over the years have had what felt like valid spiritual experiences. .... Evolutionary psychology, the modern Darwinian understanding of human nature, ... explain[s] the very origins of religious belief as the residue of built-in distortions of perception and cognition; natural selection didn't design us to believe only true things, so we're susceptible to certain kinds of falsehood. But ... our normal states of consciousness are in a sense arbitrary; they are the states that happen to have served the peculiar agenda of mundane natural selection. That is, they happen to have helped organisms (our ancestors) spread genes in a particular ecosystem on a particular planet. .... The psychologist William James .... explored the influence on consciousness of things ranging from meditation to nitrous oxide and concluded that "our normal waking consciousness" is "but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness enttirely different." James's position in the book -- that these alternative forms may be in some sense more truthful than ordinary consciousness -- is the properly open-minded stance, and it has if anything been strengthened by evolutionary psychology.

This leads Wright to the "not outlandish metaphysical prospect: there is such a thing as pure contemplative awareness, but our evolved mental machinery, in its normal working mode, is harnessing that awareness to specific ends, and in the process warping it." The main point is that shamans, with their supposed privileged insights into ultimate things, emerged as powerful forces in their societies, whether for good or for ill.

There are people who think religion serves society broadly, providing reassurance and hope in the face of pain and uncertainty, overcoming our natural selfishness with communal cohesion. And there are people who think religion is a tool of social control, wielded by the powerful for self-aggrandizement -- a tool that numbs people to their exploitation ("opiate of the masses") when it's not scaring them to death. In one view gods are good things, and in one view gods are bad things.

But Wright poses another question: "Isn't it possible that the social function and political import of religion have changed as cultural evolution has marched on?" The next step is "The chiefdom, the most advanced from of social organization in the world 7,000 years ago, [which] represents the final prehistoric phase in the evolution of social organization and the evolution of religion." Wright's chapter on the age of chiefdoms focuses on Polynesia, where religion took its role as a supplement to political authority: "Across Polynesia broadly, religion encouraged exacting work and discouraged theft and other antisocial acts." And with the emergence of larger societies, the ancient city-states, the more productive a religion made its people, the more likely that religion was to survive: "So religions that encouraged people to treat others considerately -- which made for a more orderly and productive city -- would have a competitive edge over religions that didn't."

In Mesopotamia, rulers discovered that it was to their advantage to accept other cities' gods as equal to their own.

In an age when people feared gods and desperately sought their favor, an intercity pantheon of gods that divided labor among themselves must have strengthened emotional bonds among cities. Whether or not you believe that the emotional power of religion truly emanates from the divine, the power itself is real.Thus, "in the ancient world conquerors -- the great ones, at least -- were less inclined to smash the idols of their vanquished foes than to worship them." The next step is to fuse several deities into one: "The melding of religious beliefs or concepts -- "syncretism" -- is a common way to forge cultural unity in the wake of conquest, and often ... what gets melded is the gods themselves." We're on the road to monotheism.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)