A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

Sunday, July 6, 2008

The Stripper and the Terrorist

The following review appeared today in the Houston Chronicle:

The following review appeared today in the Houston Chronicle: By Andre Dubus III

Norton, 537 pp., $24.95

Novelists keep being drawn to the events of September 11, 2001, hoping to confine the heinous imponderables of that day into the shapings of fiction. Writers as various as Jay McInerney (The Good Life), Jonathan Safran Foer (Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close) and John Updike (Terrorist) have made their attempts at it.

It’s hardly surprising that Andre Dubus III should join them with his new novel, The Garden of Last Days. Even before 9/11, in his 1999 novel House of Sand and Fog, he gave us a story that reverberated with the larger conflicts between America and the Middle East. It was a deftly constructed novel about the conflict between a somewhat feckless single woman and an exiled Iranian colonel. Oprah selected it for her book club and made it a bestseller.

Nine years later, Dubus has written another novel about a single woman, April Connors, who works as a stripper at the Puma Club for Men in Sarasota, Fla. She has a three-year-old daughter, Franny, whom she usually leaves with her landlady, Jean, while she works. When Jean gets ill, April is forced to take Franny to the club and let her watch Disney videos in the manager’s office before she falls asleep. But while April is entertaining a customer in one of the club’s private rooms, Franny wakes up and goes in search of her mother.

Franny is discovered at the back door of the club by AJ Carey, a construction worker who was kicked out earlier for getting too familiar with one of the strippers. His wrist was broken in the fracas and now, full of booze and painkillers, he has come back for revenge. What happens next is not good, and it messes up several people’s already messed-up lives.

So how does 9/11 come into all this? When Dubus read news reports that some of the hijackers had visited strip clubs and hired prostitutes in the days and weeks before their final flight, he thought about writing a short story about the encounter of a terrorist and a stripper.

It might have made a potent short story, but instead this encounter is wedged into a 500-page novel where it bears only a thematic relationship to the central plot. The Garden of Last Days takes place in early September 2001, and the customer April is entertaining in the Champagne Room of the Puma Club is a young Saudi named Bassam who, a few days later, will be one of the hijackers. (Dubus has fictionalized the terrorists’ names.) In a few lines of dialogue between Bassam and April, Dubus economically sums up one of the novel’s central themes:

“ ‘I should not like you, April.’

“ ‘Why shouldn’t you?’

“He lit another cigarette, inhaled deeply. ‘Because then I would be like you. And I am not like you.’ ”

Bassam, the terrorist, can’t fulfill his mission if he drops his habit of objectifying the enemy, if he treats non-believers like April as human beings and not as targets. The operative irony here is that April herself works in a milieu in which women are objectified -- treated as sex objects and not as human beings. But the problem is that Bassam has only a thematic role in the novel. He doesn’t fit into the plot; he affects neither its origins nor its outcome. And he doesn’t fit stylistically.

Dubus tells his story in discrete segments, each narrated from a point of view limited to one of the characters: April, Bassam, AJ, Jean and a bouncer at the club named Lonnie. He has richly imagined the way each of his American characters lives and thinks. But his imagination lets him down in the portrayal of Bassam.

Dubus roots Bassam’s fanaticism in some pretty thin psychology: a mixture of Oedipus complex (his last act before leaving to board the plane is to mail a letter to his mother) and sibling rivalry with his Westernized older brother Khalid, who died when he crashed his American car. Dubus lards Bassam’s narrative with Arabic words and quotes from the Qur’an, and he resorts to stiff, archaic syntax to emphasize Bassam’s foreignness: “So often he has asked himself why do these kufar have so much power?”

The result is that Bassam’s sections of the novel feel stagy and mechanical, whereas the emotional responses and moral dilemmas faced by April, AJ and Jean are real and touching. We learn of April’s ability to separate herself as Franny’s mother from the persona she adopts when she works in the club, and of her guilt and rage when Franny’s disappearance breaks down her tendency to compartmentalize. We enter into AJ’s confusion and desperation after he makes the impulsive decision to drive away from the club with Franny in his truck. And we experience Jean’s loneliness, her possessiveness toward Franny, the child she never had, and her distaste for April’s way of life.

Dubus’ novel makes a solid impact with its searching examination of its characters’ blind self-centeredness. But it would have that impact even if Bassam’s story had never been inserted into it. For his final act on Sept. 11 has no direct effect on the lives of the other characters. In fact, where the novel is concerned, only one of the characters, the bouncer Lonnie, is even indirectly affected by what happened on 9/11. The Garden of Last Days would have been a stronger, more coherent novel if Bassam had been omitted from it.

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

The Keys to Genius

The following review appeared today in the San Francisco Chronicle:

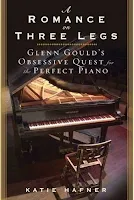

The following review appeared today in the San Francisco Chronicle:A ROMANCE ON THREE LEGS:

Glenn Gould’s Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Piano

By Katie Hafner

Bloomsbury

Concert pianists are notoriously temperamental, but with good reason: so are their pianos. Why else would J.S. Bach specify a “well-tempered clavier”? The modern piano is a jury-rigged contraption consisting of a multitude of tiny moving parts and a lot of steel and wood that has to be twisted, warped and tortured into just the right shape and structure. And it needs constant tuning, twiddling and tweaking to maintain the sound the pianist wants. No wonder that Glenn Gould, who twisted, warped and tortured himself into a great pianist, had such a love-hate relationship with the instrument that he referred to as an “intriguing mixture of pedals, pins, and paradox.”

It’s ironic that the pianoforte, as the instrument had been named because it could play both soft and loud, is now known as a piano: Virtuosi from Liszt to Lang Lang have mostly exploited the forte. But Gould wanted a piano that would sound, as he put it, “a little like an emasculated harpsichord.” He detested the Romantics, and once said his favorite composer was the 16th-century Englishman Orlando Gibbons. After a long search he found the cleanness of tone and quickness of action he wanted in a Steinway concert grand with the designation CD 318.

Katie Hafner is eloquent about why Gould loved CD 318 so much – so eloquent that one wishes her book included a discography of the recordings he made on that instrument. (His two most famous recordings – the versions of Bach’s “Goldberg Variations” he recorded in 1955 and 1981 – were made on other pianos.) “A Romance on Three Legs” is partly a biography of Gould, partly a history of Steinway & Sons, and partly a story about how technique, tastes and technology propelled the evolution of the piano. It’s also a tribute to piano tuner Verne Edquist, whose exquisite sensitivity and technical inventiveness manipulated CD 318 into an instrument almost as eccentric as Gould.

Gould insisted on using a battered old chair that had been sawed down so it was six inches shorter than a standard piano bench. He was a hypochondriac who insisted on keeping the room temperature at 80 degrees year-round, and once sued Steinway because an employee gave him an admiring pat on the back that he claimed had dislocated his shoulder, but his nose-to-the-keyboard posture must have caused many of the aches and pains of which he complained. He was a terrifying driver, who once quipped, “It’s true that I’ve driven through a number of red lights on occasion, but on the other hand I’ve stopped at a lot of green ones but never gotten credit for it.”

Hafner’s signal achievement in the book is to turn CD 318 itself into just as much a personality as Gould. Never mind that she has also demonstrated that CD 318 is just wood, steel, ivory and felt. We come to feel about CD 318 almost the way Gould did: “‘He talked about his piano as if it were human,’ fellow pianist David Bar-Illan commented.” So when CD 318 is injured in a fall … uh, damaged by being dropped, we’re shocked, and we especially empathize with Edquist, who has to break the news to Gould.

Hafner lives in the Bay Area, writes for the New York Times, and has published books about computer hackers and Internet pioneers, among other things. Some readers will complain that she touches too lightly on Gould’s faults: his undeniable gifts that were vitiated by self-indulgence; his interpretations that occasionally departed wildly from the composers’ intent; his decision to stop performing before audiences for the last 18 years of his life, and to concentrate on recording, in which mistakes can be edited out, making him appear to be technically flawless.

But the book is less a critique of Gould than an examination of an essential relationship, the one between artist and medium, as magnified by one artist’s obsession. Hafner’s book belongs to that gee-whiz genre perfected by writers like John McPhee, Susan Orlean and Mary Roach: books that tell you everything about subjects – oranges, orchids, corpses, pianos – that you didn’t know you wanted to know anything about. And for readers familiar with Gould’s recordings, or those with a curiosity about how things like pianos get to be the way they are, “A Romance on Three Legs” is a source of delight and illumination.

Sunday, June 22, 2008

Portraits of the Artist as Young Men

The following review appeared today in the Houston Chronicle:

The following review appeared today in the Houston Chronicle:ALL THE SAD YOUNG LITERARY MEN

By Keith Gessen

Viking, 242 pp., $24.95

The Germans have a word for it: Bildungsroman. Roman means “novel,” and Bildung is, well, “education” and “development” and “formation” and a lot of other stuff all packed into one word. A Bildungsroman is a more-or-less-veiled autobiographical novel about a young person’s coming of age. Charles Dickens wrote two of them, Great Expectations and David Copperfield. George Eliot’s was The Mill on the Floss, D.H. Lawrence’s was Sons and Lovers, Thomas Wolfe’s was Look Homeward, Angel, and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s was This Side of Paradise.

And All the Sad Young Literary Men is Keith Gessen’s. Its publication has caused a mild stir among the book world’s chatterati, because Gessen is, to go German again, a Wunderkind of the literary scene. Just 33, he is the founder and editor of a much-talked-about literary journal, n+1, and a critic who has been harsh on writers whom he finds wanting, such as Ian McEwan and Jonathan Safran Foer. He’s also involved in a long-running feud with his West Coast rival, Dave Eggers, the founder of McSweeney’s.

But you don’t need to be a devotee of lit chat to read his novel. The sad young literary men of the title are named Mark, Keith and Sam, and their stories, which connect only tangentially, are told in separate chapters, rotating through the book. All three are aspects of the author. Keith is the most obvious one, because he not only shares the author’s name and his Russian origins – Gessen was born in Moscow and came to the States when he was 6 years old – but he also narrates his sections of the book in first person. But Sam, like the author, lives in Brooklyn and went to Harvard, and Mark is a graduate student in history at Syracuse University, where Gessen got an M.F.A. in the writing program.

We meet Mark first, living with Sasha, whom he met in Moscow while doing research. It’s 1998 and they live in arty poverty in Queens: “To be poor in New York was humiliating, a little, but to be young – to be young was divine.” But time passes and Sasha leaves, and Mark sinks into the ennui of writing a dissertation on one of the lesser Mensheviks. He has dalliances with various women toward whom he takes a characteristically intellectual approach. He “had spent his twenties, even that portion of his twenties that he spent married, preoccupied with the problem of sex. He considered it in the positivist tradition of how to find it, of course, but also, and more significant, in the interpretivist or postmodernist tradition of how to think about it, how to ponder it historically, how to discourse about and critique it.” Sex in the head, D.H. Lawrence called it.

Sam comes out of Harvard planning to write “the great Zionist epic,” undeterred by the fact that he’s never been to Israel and doesn’t read Hebrew: When he tried to learn the language, “the letters looked like Tetris pieces.” When he gets a book contract, he develops writer’s block – he even stops “writing the occasional online opinion piece about the Second Intifada.” And to his dismay, that causes his presence on Google, evidence of his existence, to decline. He calls up Google to plead with someone to “up my count a little until I get back on my feet.” Eventually, Sam will get it together and go to Israel, where reality will set his life on a different course.

Keith’s story begins in a no less disillusioning manner: an encounter on the street with Lauren, his Harvard roommate’s former girlfriend, and her father, “the former Vice President” who “wore his beard, his infamous beard” – i.e., the one Al Gore grew after losing the election of 2000, though none of Gore’s daughters is called Lauren. Keith, who is “hurt” by Lauren’s failure to introduce him to her father, has a burgeoning career as a lefty literary intellectual at the beginning of a post-literary era dominated by a right-wing administration with a discernible bias against any intellectuals other than the ones who contribute to the Weekly Standard. The times -- for Keith and Sam and Mark -- are out of joint.

It’s possible to dismiss this novel as another fine whine from another elitist writer. And by invoking with his title Fitzgerald’s story collection All the Sad Young Men and by inviting the parallel of Gessen’s Harvard to the Princeton that was the backdrop for Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise, Gessen is displaying brazen chutzpah. Mark and Sam and Keith are not in themselves as interesting as he seems to think they are, and he hasn’t put enough imagination into creating secondary characters who might serve as foils to them. As characters, the women in the book are evanescent, even though they are a central concern … no, obsession of the three protagonists.

But there is wit at work in the novel, and as a document of the times, as a reflection of the alienation of young American intellectuals in the first decade of the 21st century, All the Sad Young Literary Men may be the kind of book that people will pick up years from now – just as we pick up Fitzgerald’s chronicles of the Jazz Age, or books by Britain’s Angry Young Men of the 1950s -- and say, “Oh, that’s what it must have been like.”

Sunday, May 25, 2008

Under Siege

The following review appeared today in the Dallas Morning News:

The following review appeared today in the Dallas Morning News: CITY OF

By David Benioff

Viking, 258 pp., $24.95

“I thought it was strange that powerful violence is often so pleasing to the eye, like tracer bullets at night,” says Lev Beniov, the protagonist and narrator of City of

As Lev sums up: “The days had become a confusion of catastrophes; what seemed impossible in the afternoon was blunt fact by the evening. German corpses fell from the sky; cannibals sold sausage links made from ground human in the Haymarket; apartment blocs collapsed to the ground; dogs became bombs; frozen soldiers became signposts; a partisan with half a face stood swaying in the snow, staring sad-eyed at his killers.”

And yet from this gruesome and bizarre state of things, drawn from one of the nightmare passages of the 20th century, the siege of

Lev is 17 years old, living on his own in the starving city, where people are eating “library candy,” the glue from the binding of books, and selling the dirt from a bombed-out food warehouse because it contains melted sugar. Lev’s father is dead, a victim of Stalin’s tyranny; his mother and sister have fled to the country. When he is arrested for looting the corpse of a German paratrooper who froze to death before he hit the ground, Lev is thrown together in prison with a dashing, clever, handsome Cossack named Kolya, who has been arrested for desertion, though he had just slipped away from his unit to look for a woman to relieve his perpetual horniness.

To avoid execution, Lev and Kolya agree to an absurd mission: to find a dozen eggs so the daughter of a colonel can have a wedding cake. They venture out into the frozen no-man’s-land between the city and the German army, an odd couple who will become a trio when they’re joined by Vika, a sharpshooting guerrilla who may be an agent for the NKVD, the secret police that arrested and murdered Lev’s father. Vika is a woman about Lev’s age, disguised as a boy.

City of Thieves is premised on the possibility that it may not be entirely fiction. It begins with a screenwriter named David – Benioff adapted his first novel, The 25th Hour, for the movies, and wrote the screenplays for The Kite Runner and the forthcoming Wolverine, the latest in the X-Men series – visiting his grandparents in

That metafictional tease aside, City of

The plot is as formulaic as a buddy movie – Butch and Sundance in

Sunday, May 18, 2008

Mr. and Mrs. Shakespeare

SHAKESPEARE’S WIFE

By Germaine Greer

HarperCollins, 416 pp., $26.95

We know even less about his wife, Ann (or Anne or even Agnes) Hathaway Shakespeare. We do know that she was born in 1556 and died in 1623 (outliving him by seven years), that they married in 1582, when she was 26 and he was 18, and that their first child, Susanna, was born six months after the wedding. They had two more children, the twins Hamnet and Judith, in 1585. And that’s pretty much it for Ann, except that in his will, Shakespeare left her his “second-best bed.”

But if countless volumes can be got out of the little we know about William’s life, it’s not really surprising that Germaine Greer can get 400 pages out of Ann’s. Greer is best known – at least on this side of the

This is not to say that Shakespeare’s Wife lacks controversy. Greer’s target is what she sees as the sexism of scholars who assume that Ann was more of an impediment than a helpmeet to Shakespeare. Scholars (mostly male) have conjectured that Shakespeare was trapped in a marriage to a woman he didn’t love. They cite the disparity in ages between William and Ann, the inference that she was pregnant when they wed, their prolonged separation when he went off to

Greer’s chief target is Stephen Greenblatt, whose 2004 Shakespeare biography, Will in the World, was a bestseller. To paint her very different portrait of the Shakespeare marriage, she uses some of Greenblatt’s own history-scouring techniques, digging deep into the minute details of Elizabethan daily life. Maybe Ann wasn’t a conniving hussy who trapped a mere boy into marriage, she proposes. And maybe consummation of the marriage before the wedding ceremony was commonly accepted, maybe they weren’t separated as long or as often as is usually thought, and maybe Shakespeare didn’t leave her much in the will because he didn’t have to – she was already entitled to her share of the estate. She may well have been a capable businesswoman, supporting the family on her own while he was away. And that bed could have had both sentimental and monetary value.

The one thing Greer doesn’t do is rely heavily on the poems and plays for evidence. She does touch lightly on passages in the plays that reinforce evidence she has found elsewhere, and she dismisses the sonnets – with their implications of the poet’s affairs both gay and straight – as mostly conventional, except when she finds evidence of marital affection in them. She doesn’t even expound on marital themes in the plays, such as the jealous husband/innocent wife motif found in tragedy (Othello), comedy (The Merry Wives of Windsor) and romance (A Winter’s Tale).

What she does give us in her account of the life led by women in Elizabethan Stratford-upon-Avon, is sometimes fascinating. And sometimes it’s tedious and tendentious. There’s a long and mostly irrelevant description of what the medical practice of John Hall, the husband of Ann and William’s daughter Susanna, must have been like. And an equally detailed account of the conflict in Stratford over the enclosure of land once held in common, in which Greer suggests Ann and her daughters might have taken part – and then admits “perhaps none of them” did. And there’s a gruesome section on syphilis and its treatment, all in service of the possibility that William might have contracted it in the brothels of

The result is a bit of a jumble of a book. There are flashes of insight, and the suggestion that Ann may not have been such a burden to her husband as some have argued is a sensible one. But a barrage of facts about everything from childbirth in Elizabethan times to the making of ale to the price of land doesn’t constitute a full portrait of Shakespeare’s wife, or add very much to our understanding of his art.

WILL IN THE WORLD: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare

By Stephen Greenblatt

Norton, 406 pp., $26.95

Perhaps. Probably. Maybe. These words hiccup through any biography of Shakespeare, and Stephen Greenblatt's is no exception. For the facts about Shakespeare's life are, as Greenblatt puts it, ''abundant but thin.'' We know all sorts of stuff about the property he bought and sold, the taxes he paid, the theatrical companies he worked for. We have his baptismal record, his marriage license and his last will and testament.

What we don't have are letters, diaries, manuscripts or anything that would give us, in Greenblatt's words, ''direct access to his thoughts about politics or religion or art.'' We want the People magazine profile, the Terry Gross interview, the ''E! True Elizabethan Story.''

But we're not going to get them, so let's be happy with the perhapses supplied by Greenblatt, a professor of humanities at Harvard. His new book, Will in the World, manages to be what a popular biography written by a noted scholar should be: readable but learned, speculative but carefully documented.

As his title suggests, Greenblatt draws his probabilities not only from the documents and the poems and plays, but also from the world Shakespeare lived in. Greenblatt imagines an 11-year-old dazzled by the pageantry surrounding the queen, who stayed at Kenilworth, 12 miles from

He sees 18-year-old Will marrying 26-year-old Anne Hathaway six months before their first child was born, and speculates that the marriage was an unhappy one, reflected in the exhortations against premarital sex and skepticism about marriage found in the plays. The only married couples in the plays who have ''a relationship of sustained intimacy,'' Greenblatt notes, ''are unnervingly strange: Gertrude and Claudius in Hamlet and the Macbeths. These marriages are powerful, in their distinct ways, but they are also upsetting, even terrifying, in their glimpses of genuine intimacy.''

But we don't really know if an unhappy marriage prompted Shakespeare to seek his fortune in

And when disease wasn't killing people, Queen Elizabeth was. The heads of traitors were stuck on poles on the Great Stone Gate leading to

Greenblatt believes that the political and religious tensions of the age taught Shakespeare some ''powerful lessons about danger and the need for discretion, concealment, and fiction.'' The heads on the bridge, Greenblatt writes, ''may have spoken to him on the day he entered

Unlike some biographers, Greenblatt doesn't rely too heavily on the sonnets for clues. He accepts that the Earl of Southampton is the ''likeliest candidate by far'' as the young man addressed in the poems, but he calls the efforts to name the other figures -- the Dark Lady, the Rival Poet -- ''beyond rashness.'' He's also cautious about speculating whether the intimate way the poet addresses the young man indicates that Shakespeare was gay. Sonnet-writing, Greenblatt says, was a kind of game, the point of which ''was to sound as intimate, self-revealing, and emotionally vulnerable as possible, without actually disclosing anything compromising to anyone outside the innermost circle.'' And Shakespeare played that game better than anyone.

Most of all, Greenblatt gives us what he calls ''an amazing success story,'' that of a bright young man from the provinces who took on the challenge of working amid playwrights better-educated than he was -- and won. There was the brilliant but unstable Christopher Marlowe, whose Tamburlaine inspired Shakespeare to his first success, the Henry VI trilogy. There were the university-educated playwrights who gathered around the corpulent and dissolute Robert Greene, who attacked Shakespeare in print as an ''upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers.''

Shakespeare far outdid these rivals, even transforming the unsavory Greene into one of his most beloved characters, Falstaff. ''What Falstaff helps to reveal is that for Shakespeare, Greene was a sleazy parasite, but he was also a grotesque titan,'' Greenblatt says.

By the time we reach the mature works, the biographical mysteries recede, as Greenblatt explores Hamlet, Macbeth, King Lear, The Tempest and other plays not only for what they tell us about Shakespeare, but also for what Shakespeare and his world tell us about the plays.

Which is as it should be. The biographical mysteries are really less interesting than the artistic mysteries: the melancholy wit of Twelfth Night, the erotic entanglements of Antony and Cleopatra, the power maneuvers of the history plays, the bittersweet magic of the late romances, the rootless malevolence of Iago, the airy dazzle of Rosalind, the stubborn humanity of Bottom, and so on -- not forgetting all those well-shaped words.

Fortunately, Greenblatt never forgets that the works are uppermost. He has given us a clever and alive book, one that makes us makes us return to Shakespeare's work with a fresh vision, and one that finds a living person in the mass of dry documents and the heaps of conjecture. Scholars may quibble about the way Greenblatt reads the facts -- it's their job to do so -- but I felt a little closer to knowing the unknowable Shakespeare than I did before I read the book.

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

Monday, May 12, 2008

Sunday, May 11, 2008

To War Is Human

The following review appeared today in the Houston Chronicle:

PEACE

By Richard Bausch

Knopf, 171 pp., $19.95

If war didn’t exist, novelists would have to invent it. What other pursuit reduces humanity to a raw essence and brings into question the nature of civilization?

Richard Bausch’s Peace is a very short novel. Some would call it a novella, but that diminutive doesn’t do the book justice. For with a kind of magical economy, Bausch packs more into 171 pages than some novelists do with three times that number. He has written 10 previous novels, and he has learned how to propel a story, to lay traps for the reader, to entice one into turning the page. In his latest novel, he not only tells a story, but he also gives his characters back-stories, illumines their inner lives, and even finds room for a couple of subplots. But the book owes equally as much to his work in short fiction – he has seven volumes of stories. He knows the importance of placing the right word, the right image, in the right place.

The main plot is a familiar one: a patrol goes out on reconnaissance; some of them kill, and some of them are killed. The three principal characters are straight out of the melting-pot cast of a Hollywood World War II movie: a Catholic, a Jew, and a foul-mouthed bigot from the

It is the winter of 1944.

It is a miserable climb. Freezing rain turns to snow as they go higher. Marson, the novel’s central character, suffers the agony of a blistered foot. Asch and Joyner bicker constantly. And when they find where the Germans are – or have been – a sniper attacks.

Has the old man led them into a trap? For the enigmatic Italian, who understands – or claims to understand – only a few words of English, was once their enemy, as Joyner keeps reminding them. “Non sono fascista,” the old man insists, every time Joyner utters the word “Fascist.” But from the moment we first see him driving his cart along the road, the man evokes the traditional image of Death: “A crooked shape in brown, a hooded man with dark thin hands, held the reins. Under the hood was only the suggestion of a gaunt face in shadow.”

Thus Bausch gives us a story with the resonance of a fable, but permeated with psychological realism. Here is Marson, alone, undertaking a crucial mission: “Not quite gradually, but with a slow widening of himself, he felt a lessening of tension, as if something had been released in his blood, a drug, preventing him from feeling what he had felt only seconds before.” And after he has completed his mission, “He had the sense, again without words, that life – all life, the life he had led and the life he had come to – had never been so suffused with clarity, a terrible inhuman clarity, made utterly out of precision, like the precision of gear and tackle in a machine. Except that he understood, in a sick wave, that this was utterly and only human.”

For that is Bausch’s point: War is human. And recognizing the moral implications of that fact can be shattering.

Thursday, May 1, 2008

Or Maybe Betting on the Wrong Tree?

"Everybody was barking at the wrong horse."