A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Saturday, January 7, 2017

The Sound and the Fury (James Franco, 2014)

James Franco gets mocked for overreaching -- writing fiction, directing avant-garde films and multimedia art, taking graduate level courses at a variety of universities simultaneously -- and for what many see as an eccentric persona. So I don't want to come off as a mocker in my criticism of his film version of William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury. It's a failure for a variety of reasons, not least the extreme difficulty of translating into visual terms a novel that succeeds in the way its author uses language to convey the inner states of his characters. Franco makes the serious mistake of casting himself as the most interior and inarticulate of Faulkner's characters, the mentally handicapped Benjy Compson. Distractingly outfitted with oversize front teeth, Franco struggles to portray Benjy's torment at the loss of his beloved sister Caddy (Ahna O'Reilly), amid the declining fortunes of the Compson family. He can't dim the intelligence in his own eyes enough to suggest the blind struggle of memory and desire and frustration within the character. The screenplay by Matt Rager, who has also adapted Faulkner's As I Lay Dying (2013) and John Steinbeck's In Dubious Battle (2016) for Franco to direct, does a fairly good job of sticking to the narrative line of the novel: Benjy's loss, the suicide of his older brother Quentin (Jacob Loeb), the marriage that Caddy enters into because she is impregnated by Dalton Ames (Logan Marshall-Green), Caddy's sending her daughter, also named Quentin (Joey King), to live with the Compsons, and the rage of the youngest brother, Jason (Scott Haze), when the teenage Quentin runs away from home with the money he has hoarded after stealing it from the funds Caddy has sent for Quentin's support. Rager also draws heavily on the sententious speeches of the Compson children's ineffectual alcoholic father (Tim Blake Nelson), taken directly from the novel. The screenplay skimps on the key role played in the novel by the black servants, particularly that of Dilsey (Loretta Devine). Most of the performances are quite good, with the exception of Janet Jones Gretzky as the mother; she looks far too healthy, and never strikes the note of decayed gentility that the role demands. There are also some unnecessarily distracting cameos by Seth Rogen as a telegraph clerk and Danny McBride as the sheriff, bit parts that didn't need to be cast so prominently. As a whole, the film feels like the work of an amateur filmmaker with exceptional film industry connections, and that, I guess, is the very definition of overreaching.

Friday, January 6, 2017

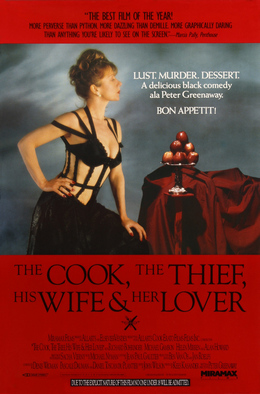

The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (Peter Greenaway, 1989)

I have to imagine some naive young person whose idea of outrageous filmmaking extends no further than the work of David Lynch or Quentin Tarantino, and who knows Helen Mirren only as the Oscar winner for The Queen (Stephen Frears, 2006) and as a dame of the British Empire, coming across The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover. It's a full-fledged assault on conventional movies, so provocative that it feels like it was made a decade or so earlier, when filmmakers were testing the limits, and not in the comparatively timid 1980s. The title itself sounds like the setup for a dirty joke, but writer-director Peter Greenaway delivers much more than that. The Cook (Richard Bohringer) runs the kitchen at a fancy restaurant that has been taken over by the Thief (Michael Gambon) and his retinue of thugs, who make a mess of things every night. Meanwhile, the Thief's Wife (Mirren) is carrying on an affair with her bookstore-owner Lover (Alan Howard) in every nook and cranny of the restaurant they can find. When the Thief finds out, the lovers hide from him at the book depository, but the Thief finds and murders him by stuffing pages from books down his throat. Eventually, the Wife, with the culinary assistance of the Cook, takes revenge in a most unappetizing way. The whole thing is played in the most over-the-top fashion imaginable, but the skill and daring of the actors makes it compelling. Gambon makes the Thief so colossally vulgar that we laugh almost as much as we cringe. Mirren and Howard are naked for great stretches of the film, but the effect is less erotic than you might think; instead, it emphasizes their vulnerability. Add to that the extraordinary production design of Ben van Os and Jan Roelfs, the sometimes kinky costume design by Jean-Paul Gaultier, the cinematography of Sacha Vierny, and the musical score by Michael Nyman, and what you have is undeniably a work of art -- perverse and sometimes extremely unpleasant, but decidedly unforgettable.

Thursday, January 5, 2017

The Royal Tenenbaums (Wes Anderson, 2001)

Etheline Tenenbaum: Anjelica Huston

Chas Tenenbaum: Ben Stiller

Margot Tenenbaum: Gwyneth Paltrow

Richie Tenenbaum: Luke Wilson

Eli Cash: Owen Wilson

Raleigh St. Clair: Bill Murray

Henry Sherman: Danny Glover

Dusty: Seymour Cassel

Pagoda: Kumar Pallana

Ari Tenenbaum: Grant Rosenmeyer

Uzi Tenenbaum: Jonah Meyerson

Narrator (voice): Alec Baldwin

Director: Wes Anderson

Screenplay: Wes Anderson, Owen Wilson

Cinematography: Robert D. Yeoman

Production design: David Wasco

Film editing: Dylan Tichenor

Music: Mark Mothersbaugh

It's hard to be droll for an hour and a half, and The Royal Tenenbaums, which runs about 20 minutes longer than that, shows the strain. Still, I don't have the feeling with it that I sometimes have with Wes Anderson's first two films, Bottle Rocket (1996) and Rushmore (1998), of not being completely in on the joke. This time it's the wacky family joke, familiar from George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart's You Can't Take It With You and numerous sitcoms. It works in large part because the cast plays it with such beautifully straight faces. And especially because it's such a magnificent cast: Gene Hackman, Anjelica Huston, Ben Stiller, Gwyneth Paltrow, Luke Wilson, Owen Wilson (who co-wrote the screenplay with Anderson), Bill Murray, and Danny Glover. It's also beautifully designed by David Wasco and filmed by Robert D. Yeoman, with Anderson's characteristically meticulous, almost theatrical framing. Hackman, as the paterfamilias in absentia Royal Tenenbaum, is the cast standout, in large part because he gets to play loose while everyone else maintains a morose deadpan, but also because he's an actor who has always been cast as the loose cannon. Even in films in which he's supposed to be reserved and repressed, such as The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974), he keeps you waiting for the inevitable moment when he snaps. Here he's loose from the beginning, but he doesn't tire you out with his volatility because he knows how much of it to keep in check at any given moment.

Wednesday, January 4, 2017

Captain America: Civil War (Anthony Russo and Joe Russo, 2016)

|

| Sebastian Stan and Chris Evans in Captain America: Civil War |

Tony Stark / Iron Man: Robert Downey Jr.

Natasha Romanoff / Black Widow: Scarlett Johansson

Bucky Barnes / Winter Soldier: Sebastian Stan

Sam Wilson / Falcon: Anthony Mackie

Lt. James Rhodes / War Machine: Don Cheadle

Clint Barton / Hawkeye: Jeremy Renner

T'Challa / Black Panther: Chadwick Boseman

Vision: Paul Bettany

Wanda Maximoff / Scarlet Witch: Elizabeth Olsen

Scott Lang / Ant-Man: Paul Rudd

Sharon Carter: Emily VanCamp

Peter Parker / Spider-Man: Tom Holland

Zemo: Daniel Brühl

Brock Rumlow / Crossbones: Frank Grillo

Secretary of State Thaddeus Ross: William Hurt

Everett K. Ross: Martin Freeman

May Parker: Marisa Tomei

King T'Chaka: John Kani

Howard Stark: John Slattery

Maria Stark: Hope Davis

Miriam: Alfred Woodard

Director: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo

Screenplay: Christopher Markus, Stephen McFeely

Cinematography: Trent Opaloch

Production design: Owen Paterson

Film editing: Jeffrey Ford, Matthew Schmidt

Music: Henry Jackman

Perhaps the greatest contribution of science to science fiction in recent years has been the theory of multiple universes, or that the universe is actually a multiverse. It enables sci-fi writers, especially those who create comic books, television shows, and movies that feature superheroes, to get away with almost anything. Marvel has created its own Marvel Cinematic Universe, which teems with superpeople out to solve the world's problems and as a consequence sometimes screwing things up even more. The Marvel world has even recognized the screwups caused by the plethora of mutants, aliens, and wealthy scientists both good and bad, to the point that after the damage caused in Sokovia -- as seen in Avengers: Age of Ultron (Joss Whedon, 2015) -- the United Nations has put together the Sokovia Accords, designed to regulate the activities of superheroes. Unfortunately, this doesn't sit well with Captain America, who is a bit of a Libertarian, especially when enforcing the accords threatens his old friend Bucky Barnes, aka the Winter Soldier -- see Captain America: The Winter Solder (Anthony Russo and Joe Russo, 2014). So Cap's attempt to defend Barnes puts him at odds with Tony Stark, aka Iron Man, who thinks the Avengers need to display good faith with the accords. And so it goes, with various superheroes taking sides and doing battle for the cause they choose. The problem with Captain America: Civil War is essentially that of Avengers: Age of Ultron: Unless you're a Marvel Comics geek, you need a playbill in hand to figure out who's who and what their superpower is. Or you can, like me, just sit back and enjoy the ride. The Russo brothers have a skillful hand at keeping all of the mayhem going, and the screenplay by Christopher Marcus and Stephen McFeely provides enough quieter moments between the CGI-enhanced action sequences to stave off a headache. But the movie really does feel overpopulated at times: In addition to the combatants mentioned, there are also Scarlett Johansson's Black Widow, Anthony Mackie's Falcon, Don Cheadle's War Machine, Jeremy Renner's Hawkeye, and a few newcomers like Paul Rudd's Ant-Man and Tom Holland as the latest incarnation of Spider-Man, the previous actors, Tobey Maguire and Andrew Garfield, having outgrown the role. There's some good quippy fun among the various members of the cast when they're not showing off their superpowers.

Tuesday, January 3, 2017

Topper (Norman Z. McLeod, 1937)

|

| Roland Young, Cary Grant, and Constance Bennett in Topper |

Monday, January 2, 2017

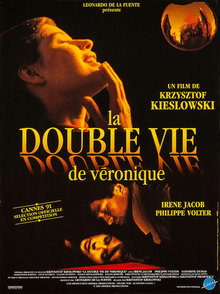

The Double Life of Véronique (Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1991)

The Netflix series Sense8 is about eight people born at the same moment in widely dispersed parts of the world. Each possesses the psychic gift to communicate with the others, sometimes to rescue one of the eight from danger. (They also occasionally participate in rather impressive group sex. Perhaps as a team-building exercise.) Sense8 takes the ancient idea that everyone has a Doppelgänger -- a physical and sometimes psychic twin -- and cubes it, eliminating the physical identity while boosting the psychic one. Krzystof Kieslowski sticks to the more traditional idea of the Doppelgänger in The Double Life of Véronique, in which Irène Jacob plays both a Polish woman named Weronika and a French woman named Véronique. Neither is fully aware of the other's existence, although Weronika once tells her father that she doesn't feel alone in the world, and Véronique tells hers that she has a feeling she has lost someone, as indeed she has: Weronika has died. Their paths crossed only once, when Véronique visited Kraków as a tourist, but although Weronika saw her double on a tour bus, Véronique learns of her existence only later, when she examines a photograph she took that includes Weronika. Kieslowski's film, from a screenplay he wrote with Krzysztof Piesewicz, deals with the parallel lives of the two women and with their emotional and symbolic intersections. It's all remarkably done, with a superb performance by Jacob that equals and sometimes surpasses her work in Kieslowski's Three Colors: Red (1994), and extraordinarily expressive cinematography by Slawomir Idziak that manipulates colors with haunting effect. As with Red, however, I feel a bit let down by Kieslowski's tendency to go for sentiment: I'm left with a feeling that there's something hollow at the film's core, a lack of substance underlying the impressive acting and technique. Still, a lesser director than Kieslowski might have gone all the way, to a Hollywood-style romantic ending instead of the somewhat ambiguous one he gives us.

Sunday, January 1, 2017

Two From Hawks

The Thing From Another World (Christian Nyby, 1951)

Capt. Patrick Hendry: Kenneth Tobey

Nikki Nicholson: Margaret Sheridan

Dr. Arthur Carrington: Robert Cornthwaite

Ned Scott: Douglas Spencer

Lt. Eddie Dykes: James Young

Crew Chief, Bob: Dewey Martin

Lt. Ken Erickson: Robert Nichols

Cpl. Barnes: William Self

Dr. Stern: Eduard Franz

The Thing: James Arness

Director: Christian Nyby

Screenplay: Charles Lederer, Howard Hawks, Ben Hecht

Based on a story by John W. Campbell Jr.

Cinematography: Russell Harlan

Art direction: Albert S. D'Agostino, John Hughes

Film editing: Roland Gross

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

Monkey Business (Howard Hawks, 1952)

Barnaby Fulton: Cary Grant

Edwina Fulton: Ginger Rogers

Oliver Oxley: Charles Coburn

Lois Laurel: Marilyn Monroe

Hank Entwhistle: Hugh Marlowe

Jerome Kitzel: Henri Letondal

Dr. Zoldeck: Robert Cornthwaite

G.J. Culverly: Larry Keating

Dr. Brunner: Douglas Spencer

Mrs. Rhinelander: Esther Dale

Little Indian: George Winslow

Director: Howard Hawks

Screenplay: Ben Hecht, Charles Lederer, I.A.L. Diamond, Harry Segall

Cinematography: Milton R. Krasner

Art direction: George Patrick, Lyle R. Wheeler

Film editing: William B. Murphy

Music: Leigh Harline

|

| James Arness in The Thing From Another World |

Nikki Nicholson: Margaret Sheridan

Dr. Arthur Carrington: Robert Cornthwaite

Ned Scott: Douglas Spencer

Lt. Eddie Dykes: James Young

Crew Chief, Bob: Dewey Martin

Lt. Ken Erickson: Robert Nichols

Cpl. Barnes: William Self

Dr. Stern: Eduard Franz

The Thing: James Arness

Director: Christian Nyby

Screenplay: Charles Lederer, Howard Hawks, Ben Hecht

Based on a story by John W. Campbell Jr.

Cinematography: Russell Harlan

Art direction: Albert S. D'Agostino, John Hughes

Film editing: Roland Gross

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

Monkey Business (Howard Hawks, 1952)

|

| Ginger Rogers, Charles Coburn, and Marilyn Monroe in Monkey Business |

Edwina Fulton: Ginger Rogers

Oliver Oxley: Charles Coburn

Lois Laurel: Marilyn Monroe

Hank Entwhistle: Hugh Marlowe

Jerome Kitzel: Henri Letondal

Dr. Zoldeck: Robert Cornthwaite

G.J. Culverly: Larry Keating

Dr. Brunner: Douglas Spencer

Mrs. Rhinelander: Esther Dale

Little Indian: George Winslow

Director: Howard Hawks

Screenplay: Ben Hecht, Charles Lederer, I.A.L. Diamond, Harry Segall

Cinematography: Milton R. Krasner

Art direction: George Patrick, Lyle R. Wheeler

Film editing: William B. Murphy

Music: Leigh Harline

Oddly, the most "Hawksian" of these two early 1950s Howard Hawks movies is the one for which he is credited as producer and not as director. The fact that The Thing From Another World displays Hawks's typical fast-paced, overlapping dialogue and has a heroine who can hold her own around men has led many to suggest that Hawks really directed it. The rumor is that Hawks gave Christian Nyby the director's credit so that Nyby could join the Directors Guild. It was the first directing credit for Nyby, who had worked as film editor for Hawks on several films, including Red River (Hawks, 1948), for which Nyby received an Oscar nomination. He went on to a long career as director, mostly on TV series like Bonanza and Mayberry R.F.D., but the controversy over whether he or Hawks directed The Thing has never really quieted down. In any case, The Thing is a landmark sci-fi/horror film, with plenty of wit and some engaging performances, particularly by Margaret Sheridan as the no-nonsense Nikki, secretary to a scientist at a research outpost near the North Pole where a flying saucer has crashed with a mysterious inhabitant. Nikki's old flame, Capt. Hendry, arrives with an Air Force crew to investigate, and Sheridan and Tobey have a little of the bantering chemistry of earlier Hawksían couples like Bogart and Bacall in To Have and Have Not (1944) or Montgomery Clift and Joanne Dru in Red River. Though it's a low-budget cast, everyone performs with wit and conviction. The film has dated less than other invaders-from-outer-space movies of the '50s, partly because of its lightness of touch and a few genuine scares, though its concluding admonition, "Watch the skies," is pure Cold War paranoia at its peak. That's James Arness, pre-Gunsmoke, as the Thing. The screenplay is by Charles Lederer, with some uncredited contributions from Ben Hecht, both of them frequent collaborators with Hawks. Both of them also worked on Monkey Business, a very different kind of movie, whose writers also include Billy Wilder's future collaborator, I.A.L. Diamond. The film evokes Hawks's great Bringing Up Baby (1938) by featuring Cary Grant as a rather addled scientist, Dr. Barnaby Fulton, who becomes involved in some comic mishaps brought about by an animal -- a leopard in the earlier film, a chimpanzee in this one. But the giddiness of Bringing Up Baby never quite emerges, partly because of a lack of chemistry between Grant and Ginger Rogers, who plays his wife, Edwina. The script involves Fulton's work on a rejuvenating drug that the chimpanzee manages to empty into a water cooler, thereby turning anyone who drinks it into an irresponsible 20-year-old. Grant is an old master at this kind of nonsense, but Rogers looks stiff and starchy and ill-at-ease trying to match him -- except, of course, when she is called on to dance, which she still did splendidly. Fortunately, there's some engaging support from Charles Coburn as Fulton's boss, who has a "secretary" played by Marilyn Monroe. ("Find someone to type this," he tells her.) Her role is the air-headed blonde stereotype that she found so difficult to escape -- "Mr. Oxley's been complaining about my punctuation, so I'm careful to get here before nine," she tells Fulton -- but no one has ever been better at playing it. Where The Thing From Another World succeeds despite a less-than-stellar cast, Monkey Business depends heavily on star power, for it gives off a feeling that its genre, screwball comedy, had played out by the time it was made.

Wednesday, December 28, 2016

Amour (Michael Haneke, 2012)

|

| Emmanuelle Riva in Amour |

Anne: Emmanuelle Riva

Eva: Isabelle Huppert

Alexandre: Alexandre Tharaud

Geoff: William Shimell

Concierge: Rita Blanco

Concierge's Husband: Ramón Agirre

Director: Michael Haneke

Screenplay: Michael Haneke

Cinematography: Darius Khondji

As someone who knows what it's like to care for a disabled spouse, I commend writer-director Michael Haneke for getting so much right in Amour. Not that accuracy is of the essence in the film: Amour is not a documentary, it's a fiction, and as such needs a shape that lies beyond the depiction of the mundane pains and frustrations of the characters. And that way lie the pitfalls of sentimentality and melodrama, which Haneke mostly avoids, thanks in very large part to the brilliance of his actors, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Emmanuelle Riva, and Isabelle Huppert. Are there American actors, or even British ones, who could have performed these roles with commensurate skill, drawn from the depths of experience? Trintignant and Riva are Georges and Anne, retired piano teachers whom we first see at the triumphant performance by one of her former pupils, Alexandre (the real pianist Alexandre Tharaud). Shortly afterward, Anne suffers a mild stroke and submits to surgery to eliminate an arterial blockage, but the surgery leaves her paralyzed on the right side. Georges is able to cope with his caregiving duties, though Anne is increasingly distressed by her disability and by the burden it places on her husband. At one point she tells him that she wants to die. Another stroke then leaves her mostly speechless and virtually helpless, forcing Georges to hire part-time nursing help. Their daughter, Eva (Huppert), has her own life to live, and urges Georges to put Anne in institutional care, which he resists because of Anne's previously expressed wish to die in their home, not in a hospital. Unfortunately, despite inspired performances and mostly sensitive direction, the climax and the conclusion of Amour ring a little false, perhaps because the fictional construct demands a somewhat artificial closure to a film that has felt genuine up to that point. Amour received Oscar nominations for best picture, for Riva's performance, and for Haneke's direction and screenplay, and it won the best foreign-language film award.

Tuesday, December 27, 2016

Son of Saul (László Nemes, 2015)

Son of Saul begins with an out-of-focus figure walking across a field toward the camera until he finally comes into focus. This is Saul Ausländer (Géza Röhrig), a Sonderkommando -- a Jewish prisoner tasked with clean-up duties in a Nazi death camp. In a bravura sequence, the camera (the cinematographer is Mátyás Erdély) stays focused on Saul in near-closeup as it tracks what he is doing: helping herd naked people into the "showers" where they are gassed, rifling through their belongings that they have neatly hung up in an anteroom (they were, in a particularly sadistic stroke, told to remember the numbers of the hooks on which they hung their clothes and to hurry their showers because the promised soup is getting cold), then helping take the bodies (referred to by the Nazis as "die Stücke," or "pieces") to the crematorium, and scrubbing the floors in the gas chamber. It's a sequence made more horrifying by the fact that all of these events take place in the slightly out-of-focus background as the camera concentrates on Saul. But something out of the ordinary happens: A boy is found still alive in the gas chamber, and Saul recognizes him. He will later tell others that the boy is his son, from a liaison with a woman not his wife, which explains the unusual interest he takes in this particular victim: When the boy is sent to the doctors, he is smothered to death by an SS officer who then orders an autopsy to try to explain why he survived the gas. Saul, who witnesses this murder, persuades a sympathetic doctor to hold off on the autopsy and keep the body from being cremated. Saul's efforts to hide the body and to find a rabbi who can perform a ritual burial form the rest of the film's narrative. He is aided in his efforts but sometimes also resisted by other prisoners, who are plotting a rebellion against the guards. It's an extraordinarily harrowing film that won the foreign language film Oscar and numerous critics society awards. Remarkably, it's also writer-director László Nemes's first feature film, and Röhrig, on whom the camera is focused for virtually the entire time, had only a Hungarian TV miniseries made in 1989 as an acting credit. Like many films about the Holocaust it runs the risk of turning its subject into melodrama or of desensitizing the audience to the depicted horrors. It doesn't quite avoid the risk -- there are times when Saul's implacable determination tests our credulity, and there is always the awareness that these are "just actors" portraying things that happened to real people -- but it's an honorable contribution to a difficult genre.

Monday, December 26, 2016

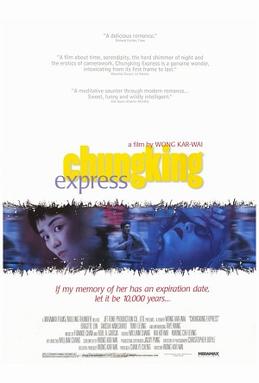

Chungking Express (Wong Kar-Wai, 1994)

The American title, Chungking Express, may echo Josef von Sternberg's 1932 Marlene Dietrich classic Shanghai Express, but it resembles that film only in the presence in both of a blond femme fatale -- and in Wong Kar-Wai's film the blond is one only by virtue of a wig. The translated title -- the original meant something like "Chungking Forest" or "Jungle" -- fuses the film's two major settings: the Chungking Mansions, a low-rent building in Hong Kong, and the Midnight Express, a sandwich shop that provides the linkage between the film's two segments. The first part deals with the infatuation of a young police detective, He Qiwu, aka Cop 223 (Takeshi Kaneshiro), with the woman in the blond wig (Brigitte Lin), who is mixed up in a drug-smuggling scheme that goes awry. The second part tells the story of Cop 663 (Tony Leung Chiu-Wai), and his involvement with Faye (Faye Wong), a young woman who works the counter at the sandwich shop. You might say that Chungking Express begins in the world of film noir and ends in that of romantic (and slightly screwball) comedy, but Wong's film transcends the simplicity of genres. As in his masterly In the Mood for Love (2000), Wong is dealing with characters on the brink of an uncertain future, but with a much lighter touch than the later film. The performances are uniformly fine. Faye Wong, a Hong Kong pop star, brings the quirky character of the young Shirley MacLaine to her role, but with a much greater fragility. Like MacLaine, she has been unfairly labeled with the Manic Pixie Dream Girl stereotype. The extraordinary cinematography is by Christopher Doyle and Wai-Keung Lau.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)