A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Thursday, April 20, 2017

Stranger Than Paradise (Jim Jarmusch, 1984)

Like a botanist discovering rare plants pushing through cracked pavement and a littered vacant lot, writer-director Jim Jarmusch finds curiously indomitable life forms in the back streets of ungentrified New York, the frozen outskirts of Cleveland, and the parts of coastal Florida that tourists speed through on their way to Orlando or Miami. And he presents them to us in a film with a beautifully eccentric rhythm to it. Stranger Than Paradise is composed of 67 single takes grouped into three sections: "The New World," in which Eva (Eszter Balint) arrives from Budapest to stay with her cousin Willie (John Lurie) in his ratty one-room New York apartment; "One Year Later," in which Willie and his friend Eddie (Richard Edson) drive to wintry Cleveland, where Eva has gone to live with her Aunt Lotte (Cecillia Stark); and "Paradise," in which Willie, Eddie, and Eva go to Florida. To say that nothing happens in the film isn't entirely incorrect, especially in the New York and Cleveland sections, in which Willie and Eddie spend most of their time playing cards, smoking, and generally getting on each other's nerves, as well as Eva's. In Florida, they lose money gambling, win it back, and Eva accidentally strikes it rich when she's mistaken for a drug runner's bagman. Yet it's the blackout structure of the film that gives it the illusion of a plot, or at least forward motion. Once you catch its rhythm, you may find yourself, as I did, eagerly anticipating the way in which Jarmusch will end each scene. He rarely does it with a gag or a punchline, but somehow in ways that make each scene feel like a kind of epiphany. In one of the longest sequences, we do nothing but watch the three major characters, plus Eva's boyfriend Billy (Danny Rosen), as they sit in a Cleveland theater watching a movie that, because it has no dialogue but is punctuated with various grunts, seems to be a kung fu film. Billy, who we learn has bought the tickets for everyone, is walled off from Eva by Eddie and Willie, who sit on either side of her, and when he passes the popcorn to Eva, Eddie takes a big handful. We learn more about these characters from this wordless sequence than we do from some of the film's expository dialogue. Tom DiCillo's black-and-white cinematography makes the most of the locations that were chosen for their blandness, bleakness, drabness, or, in the case of the frozen, snow-covered Lake Erie, emptiness. The soundtrack, composed for string quartet by Lurie, is supplemented by Screamin' Jay Hawkins's "I Put a Spell on You," a foreshadowing of Hawkins's appearance in Jarmusch's Mystery Train (1989).

Wednesday, April 19, 2017

What Price Hollywood? (George Cukor, 1932)

Bradley Cooper is reportedly directing a remake of A Star Is Born in which he and Lady Gaga will take the roles played by Fredric March and Janet Gaynor in 1937, James Mason and Judy Garland in 1954, and Kris Kristofferson and Barbra Streisand in 1976. So maybe it's a good time to check out the ur-Star Is Born, What Price Hollywood?, that was produced by David O. Selznick and directed by George Cukor in 1932. The name is different but the plot's the same: A successful man in the entertainment business discovers a young woman whom he helps become a star, but as her career ascends, his personal problems send him into a tailspin.* The idea for the film is a natural in a Hollywood that had become increasingly conscious of its own myth, and many real-life analogs have been found in the history of the industry. Selznick commissioned Adela Rogers St. Johns, a former reporter for Photoplay and the Hearst newspapers, to write the story for the film, and various other hands turned it into a screenplay, though St. Johns and Jane Murfin claimed most of the credit when they were nominated for an Oscar for best original story. The film begins with a touch of screwball comedy when Max Carey (Lowell Sherman), an alcoholic director, encounters Mary Evans (Constance Bennett), a waitress at the Brown Derby looking for her chance to break into the movies. After some funny scenes involving Max's drunkenness and Mary's initial ineptness as an actress, the movie unfortunately begins to get serious. Though it's clear Mary really loves Max, when she becomes a big star she marries a society polo player, Lonny Borden (Neil Hamilton), after a somewhat cutesy courtship. But Borden is unhappy being "Mr. Mary Evans," and eventually storms out, though she's pregnant. Meanwhile, Max's decline continues, and after Mary rescues him from the drunk tank and promises to rehabilitate him, he shoots himself, thereby embroiling her in a headline-making scandal. But then Borden returns to apologize and all is well again. What keeps the film alive despite its clichés are the performances. Bennett is quite charming, and Sherman clearly models Max on John Barrymore, whom he knew well: He was married to Helene Costello, whose sister, Dolores, was Barrymore's third wife. The supporting cast includes Gregory Ratoff as the producer of Mary's films, Louise Beavers as (of course) her maid, and Eddie Anderson as Max's chauffeur -- five years before he became famous as Jack Benny's chauffeur, Rochester, on radio.

*As if there were any doubt, there's a clear link between What Price Hollywood? and at least the first A Star Is Born in that both were produced by Selznick. RKO, which released What Price Hollywood?, threatened to sue Selznick over the similarities, but decided against it. Selznick also asked Cukor to direct the 1937 film, but Cukor declined, so William A. Wellman took it on. But then Cukor went on to direct the 1954 Star Is Born. I don't think there's any direct connection between What Price Hollywood? and the 1976 version, produced by Streisand and Jon Peters and directed by Frank Pierson, but the lineage by then was obvious.

*As if there were any doubt, there's a clear link between What Price Hollywood? and at least the first A Star Is Born in that both were produced by Selznick. RKO, which released What Price Hollywood?, threatened to sue Selznick over the similarities, but decided against it. Selznick also asked Cukor to direct the 1937 film, but Cukor declined, so William A. Wellman took it on. But then Cukor went on to direct the 1954 Star Is Born. I don't think there's any direct connection between What Price Hollywood? and the 1976 version, produced by Streisand and Jon Peters and directed by Frank Pierson, but the lineage by then was obvious.

Tuesday, April 18, 2017

Early Spring (Yasujiro Ozu, 1958)

Recurring flashes of déjà vu as I watched Yasujiro Ozu's Early Spring alerted me to the fact that I had seen the film before. As I've said, the titles of Ozu's films make it hard for even his admirers to recall which is which, and sometimes even the capsule synopses that appear with film listings aren't much help. With some filmmakers, those who depend on suspense and plot twists for effect, this kind of vagueness about what happens in any given film could be a flaw. You'd feel cheated if you found yourself watching one of their films again by mistake. But with Ozu, it's as if what happens doesn't matter so much as how it happens. For those of you who are unsure which one is Early Spring, it's the one in which Shoji Sugiyama (Ryo Ikebe), a "salaryman" for a fire-brick manufacturing company, and his wife, Masako (Chikage Awashima), are having marital problems. They have grown apart after the death of a child: He throws himself into his work, into concern over the illness of a friend, into after-hours drinking with old war buddies, and finally into a brief affair with a young woman (Keiko Kishi) he has met on the commuter train. She's called "Goldfish" because of her large eyes, and she's a rather giddy and flirtatious woman who likes to pal around with the guys. After Shoji and Goldfish are seen together on a weekend hike put together by some of their co-workers -- Masako, who is reserved and rather traditional in manner, declined to accompany him -- gossip begins to spread. Eventually it comes back to Masako, and after several incidents -- he spends the night with Goldfish and claims he was with his sick friend, he forgets to observe the anniversary of the death of their son, and he brings home two very drunk war buddies -- she leaves him. Meanwhile, Shoji has been offered a transfer to a distant manufacturing branch of his company, where he will have to spend three years in the hope that he can return to Tokyo and a promotion. Finally, he accepts the offer, and at the end Masako has joined him, thinking they can work things out. At the conclusion they watch a train go by and reflect that Tokyo -- as symbolic for them as Moscow is for Chekhov's three sisters -- is only three hours away. In their case, of course, it's three hours and three years. Characteristically, Ozu and co-screenwriter Kogo Noda tell this story in a strictly linear fashion. Another director might have been tempted to insert expository flashbacks to, for example, the death of the child. (I've noted before how in many Japanese films of the 1930s, including Ozu's 1933 Passing Fancy, the plots hinge on the illness of children. Ozu has clearly gone beyond that motif in Early Spring.) But by letting the story play out as it happens -- beginning with a "typical" day in the life of the Sugiyamas -- Ozu builds a special kind of intimacy with his characters, as we gather the clues to their behavior and sometimes their relationships along the way. This intimacy is reinforced by Ozu's signature low-angle camera, in which we build our acquaintance with the characters from the ground up, as it were. It's a film pregnant with all sorts of larger significance: the dreariness of corporate office work, the nostalgia for wartime adventure and camaraderie, the tension between tradition and modernization, none of which is allowed to overwhelm the simple human story it tells. For that reason, and many others, Early Spring bears re-watching, even unawares.

Monday, April 17, 2017

The Big Lebowski (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 1998)

|

| Jeff Bridges and Sam Elliott in The Big Lebowski |

Walter Sobchak: John Goodman

Maude Lebowski: Julianne Moore

Donny Kerabatsos: Steve Buscemi

The Big Lebowski: David Huddleston

Brandt: Philip Seymour Hoffman

Bunny Lebowski: Tara Reid

Jesus Quintana: John Turturro

Knox Harrington: David Thewlis

The Stranger: Sam Elliott

Director: Joel Coen, Ethan Coen

Screenplay: Joel Coen, Ethan Coen

Cinematography: Roger Deakins

Production design: Rick Heinrichs

Film editing: Joel Coen, Ethan Coen, Tricia Cooke

Music: Carter Burwell

The Coen brothers' movies are usually more in the vein of Billy Wilder's acerbic satire than the affectionately loopy take on the varieties of human eccentricity you find in Preston Sturges's films. But The Big Lebowski somehow manages to have touches of both Wilder and Sturges, with the latter, I think, finally predominating. Or maybe it's just that I find that Sam Elliott's appearance, mustache in full bloom, at the end of the film casts the entire movie in a benign light. (Elliott is one of those actors who can make almost any movie better just by showing up in it.) But what also brings Sturges to mind is the special texture he gave to his films with the use of his stock company of character actors like William Demarest, Franklin Pangborn, Jimmy Conlin, and the rest. And the Coens have done something similar by bringing in their usual gang: John Goodman, Steve Buscemi, John Turturro, among others. They also make use of such great actors as Philip Seymour Hoffman and Julianne Moore in supporting roles, and how can you not love a film that gives David Thewlis a bit part in which he does almost nothing but giggle? Still, The Big Lebowski would be nothing without Jeff Bridges, our least appreciated great actor, finding the right note for the stoned and indomitable Dude. He takes a licking -- gets beat up, has his rug pissed on, gets beat up again and has his replacement rug snatched from him, has his car stolen, is threatened by German nihilists, finds his car but its windows get smashed, has a mickey slipped into his White Russian, gets arrested and beaten by the Malibu police, gets thrown out of a cab because he objects to the driver's playing the Eagles, goes home to find his apartment trashed, and finally sees what's left of his car set fire to -- but the Dude abides. And somehow in the middle of all this he finds time to go bowling with Walter and Donny and perform something like Three Stooges routines (only funny) with them. It has been labeled a "cult film," but it transcends that label. Everyone who loves it has their own favorite lines: Mine happen to be "That's the stress talking" and "Hey, careful, man, there's a beverage here!" I suppose I also have to mention the contributions of Roger Deakins's cinematography and Carter Burwell's score augmented by T Bone Burnett's invaluable work as "musical archivist," but then everyone covered themselves with glory by working on The Big Lebowski.

Sunday, April 16, 2017

The Home and the World (Satyajit Ray, 1984)

Revolutions are mounted in the name of human betterment, but humanists -- those who try to act upon their belief in the potential of all human beings -- make lousy revolutionaries. That seems to be the message of Satyajit Ray's The Home and the World, an adaptation of a novel by Rabindranath Tagore that Ray had wanted to film almost his entire career. He finally overcame the obstacles to its filming in the last years of his life, but paid the price of two severe heart attacks while making it. He supervised its completion by his son, Sandip Ray. While it's rich in images and performances, the film does seem a little slow in telling its complex story. Satyajit Ray, who also wrote the screenplay, resorts occasionally to voiceovers, often a sign of uncertainty on the part of a filmmaker about whether his story is getting clearly told. The film begins with Bimala (Swatilekha Sengupta), the wife of the wealthy Nikhilesh Choudhury (Victor Banerjee), being tutored in English style and manners by Miss Gilby (Jennifer Kendal). Specifically, Bimala is learning an English parlor song, "Long, Long Ago." But Nikhil, who is a nascent liberal reformer, wonders why Bimala should be learning a foreign song. He becomes determined to free her from the strictures imposed on Indian women: Among other things, she's confined to only part of their large house -- women are forbidden to enter the part where he entertains guests. So when his friend Sandip (Soumitra Chatterjee), a spokesman for Swadeshi, the revolutionary movement protesting British rule, comes to stay in that part of the house, Nikhil takes Bimala down the corridor that connects the two parts -- shocking Bimala's widowed sister-in-law (Gopa Aich), who lives a life of idle complaining about her lot -- and introduces her to Sandip. It's an electric moment. Suddenly, not only her home but also the world of politics is opened to Bimala. Eventually, Sandip and Nikhil will have to clash, not just over Bimala but also over Swadeshi's program to have the country boycott foreign goods and learn to rely only on India-produced merchandise. The year is 1907, when the British mandated a partition of Bengal into separate Hindu and Muslim regions, and the religious separation only adds fuel to the economic conflict. Nikhil is in favor of Swadeshi up to a point, but as a man who owns a largely Muslim-run market, he also knows that eliminating foreign goods will hurt the poor, who can't afford the higher-priced Indian items. Bimala becomes the film's focal point for the division between Sandip's fervor and Nikhil's idealism, with tragic results. The three central performances are superb, and the color cinematography of Soumendu Roy and production design by Ashoke Bose are handsome, but the merger of history and romantic fiction is uneasy, with occasionally sketchy results on both counts.

Saturday, April 15, 2017

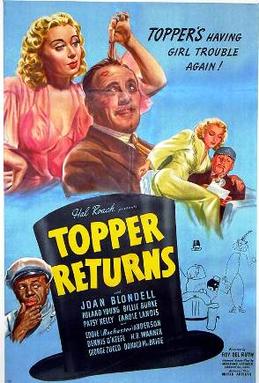

Topper Returns (Roy Del Ruth, 1941)

This silly B-picture was just the thing to unwind with after the heaviness of the last couple of posts. It's the second of two sequels to the original Topper (Norman Z. McLeod, 1937), about a stuffy banker beset by sexy ghosts. But it doesn't have much in common with the first movie other than Roland Young as Topper and Billie Burke as his fluttery, suspicious wife who mistakes his odd behavior for infidelity when the ghosts start teasing him. Cary Grant and Constance Bennett were the mischievous ghosts in the first film, but Grant jumped ship before the first sequel, Topper Takes a Trip (McLeod, 1938), after which Bennett bailed out too. This time the sexy ghost is Joan Blondell, whose character, Gail Richards, is murdered by mistake: The intended victim was her friend, Ann Carrington (Carole Landis), heir to a large fortune. Once she passes over, the ectoplasmic Gail enlists Topper, of all people, in helping solve her murder. Young is, as always, a delight -- one of the greatest comic actors ever to be underemployed by Hollywood -- but he doesn't have a lot to do this time except be shoved around by the invisible Gail as they search for clues in the creepy mansion where she was murdered. Mrs. Topper shows up, too, accompanied by her maid (Patsy Kelly) and the chauffeur, played by Eddie Anderson, billed as Eddie "Rochester" Anderson because of his fame as the eponymous chauffeur on Jack Benny's radio show. Even though he's called "Eddie" by Topper and "Edward" by Mrs. Topper, he manages to slip in a line about how he wants his old job with Mr. Benny back. Although Anderson is given some stereotypical moments predicated on the old gag that black people are afraid of ghosts, and there's a tedious slapstick bit involving a sea lion (oh, don't ask), he's treated as more of a comic equal in the film than African American actors usually were, matching wisecrack for wisecrack. There are also some funny moments with Donald MacBride as a particularly addled police detective. The whole thing is laced through with topical gags that have lost their edge: Rafaela Ottiano plays a sinister housekeeper modeled on Mrs. Danvers in Rebecca (Alfred Hitchcock, 1940), and if you don't get the joke immediately be sure that someone will refer to her as "Rebecca," even though her character's name is Lillian. The movie is also a reminder of how pervasive radio once was in popular culture: In addition to Anderson's reference to Jack Benny, there are also quips about Orson Welles's "War of the Worlds" broadcast, and a radio giveaway show called "Pot o' Gold" in which people won the jackpot if they answered their randomly dialed telephone.

Friday, April 14, 2017

Ugetsu (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953)

When does beauty become a flaw? To put it another way, if beauty is only skin deep, how does an artist present it so that we don't linger on the surface of a work and fail to comprehend its depths? I raise this in connection with a viewing of Kenji Mizoguchi's Ugetsu, a film universally praised for its beauty. It's easy to be mesmerized by Mizoguchi's visual compositions and by the sinuous fluidity of Kazuo Miyagawa's cinematography, as well as the poetry of Yoshikata Yoda's screenplay, all at the expense of feeling the coherence of the film's story and characters and ideas with our own lives. I find myself preferring Mizoguchi's less exquisite films to Ugetsu: Sansho the Bailiff (1954), surely, but also The Life of Oharu (1952) and even an earlier film like Osaka Elegy (1936). A case in point: The scene in which Genjuro (Masayuki Mori) returns home after his dalliance with the ghostly Lady Wasaka (Machiko Kyo) is a crucial and mythic one, evoking among other things Odysseus's return to Ithaca. And Mizoguchi stages it memorably: Genjuro enters the near-ruin of his house and finds it empty and littered, the fire pit cold. The camera follows him through the house in a long unbroken take, watches as he goes out the back door and sees him through the windows as he circles the house and re-enters. Only this time when he enters, the room is clean and the fire is burning brightly; his wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), embraces him. Overwhelmed and exhausted, he lies down and falls into a deep sleep beside his son, only to wake in the morning to find the cold empty room he first entered and to learn that Miyagi is dead. It's a magnificent sequence, a tour de force of acting, directing, camerawork and editing (by Mitsuzo Miyata). It makes a larger, deeper point: that Genjuro will never escape from ghosts. A less gifted director than Mizoguchi would have used conventional techniques like dissolves or double exposures to make the point. But there's also something distracting about instead employing a long, circular tracking shot with an invisible cut: We marvel at the technique at the expense of sharing Genjuro's experience. There is an art that conceals art, and I don't think Mizoguchi attains it here.

Thursday, April 13, 2017

Through a Glass Darkly (Ingmar Bergman, 1961)

Ingmar Bergman's Through a Glass Darkly is usually grouped with his films Winter Light (1963) and The Silence (1963) as a kind of trilogy about the search for God, though Bergman denied having any intent to make a trilogy. It remains one of his most critically praised films, winning an Oscar for best foreign language film and receiving a nomination for Bergman's screenplay. But there are many, like me, who find it talky and stagy, despite Sven Nykist's beautiful cinematography and the effective use of location shooting on the island of Fårö in the Baltic. Some of the staginess, I think, comes from the casting of such familiar members of Bergman's virtual stock company as Harriet Andersson, Max von Sydow, and Gunnar Björnstrand. Andersson plays Karin, a woman just out of a mental hospital where she has recovered from a recent bout with what seems to be schizophrenia. She is married to Martin (von Sydow) and they have come to stay on the island with her father, David (Björnstrand), and her younger brother, Minus (Lars Passgård). David is distracted by his attempt to finish a novel, and both of his children rather resent his preoccupation. Martin confides in David that although Karin seems to have recovered, the doctors say that her illness is incurable -- a revelation that David records in his diary. Of course, Karin reads the diary, which precipitates a crisis, during which, among other things, she seduces her own brother. At the climax of the film, Karin has a vision of God as a giant spider that attempts to rape her. After she and Martin are taken away to the hospital, David has a moment alone with Minus, whom he assures that God and love are the same thing, and that their love for Karin will help her. Minus seems consoled by this thought, but perhaps even more by the fact that he has actually had a connection with his father: "Papa spoke to me" are the last words of the film. This resolution of the film's torments feels pat and theatrical and even upbeat, which may be why Bergman went on to make the much darker films about religious faith that constitute the rest of the trilogy. But it also suggests to me why I find Bergman's films so much less satisfying than those of Robert Bresson and Carl Theodor Dreyer, both of whom wrangled with God and faith in their films. Bresson and Dreyer liked to use unknown actors, and some of the familiarity we have with Bergman's players from other films distances us from the characters. We watch them acting, not being. When Bresson is dealing directly with religious faith in a film like Diary of a Country Priest (1951) or Dreyer is telling a story about a literal resurrection in Ordet (1955), we are forced to confront our own beliefs or absence of them. Bergman simply presents faith as a dramatic problem for his characters to work out, whereas Bresson and Dreyer drag us into the messy actuality of their characters' lives.

Wednesday, April 12, 2017

Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984)

|

| Nastassja Kinski and Harry Dean Stanton in Paris, Texas |

Tuesday, April 11, 2017

Shall We Dance (Mark Sandrich, 1937)

This was the seventh teaming of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, and the fatigue is beginning to show, despite a score by George Gershwin and songs with his brother Ira. Shall We Dance is marred by a tired script -- credited to Allan Scott and Ernest Pagano -- that reworks the familiar pattern: The Astaire and Rogers characters meet cute, feel an attraction to each other that they resist, find themselves in farcical misunderstandings, and several spats, songs, and dances later assure themselves that they are in love. In this one, Astaire plays a faux-Russian ballet dancer called Petrov -- he's actually Pete Peters from Philadelphia, Pa. -- who really wants to be a tap dancer. The idea of Astaire as a danseur noble is absurd from the start, and Astaire knew it -- he had turned down the lead in the 1936 Broadway production of the Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart musical On Your Toes, which like Shall We Dance centers on a production that combines ballet with Broadway-style dance. Gershwin, too, was not entirely happy about the idea of composing ballet music, but both men were eventually persuaded to go along with the idea. The plot gimmick is that Peters/Petrov has fallen for tap dancer Linda Keene, who initially spurns him, and through a series of mishaps the rumor gets started that the two are secretly married. After much ado, they really get married so she can divorce him and put a stop to the rumors, but by then they of course have really fallen in love. One problem is that, unlike the best Astaire-Rogers films, Top Hat (Mark Sandrich, 1935) and Swing Time (George Stevens, 1936), the songs in Shall We Dance don't grow organically out of the screenplay. They have to be wedged in, like Astaire's number "Slap That Bass," which takes place in the engine room of the ocean liner on which Petrov and Linda are traveling -- one of the oddest of the Big White Sets for which the Astaire-Rogers musicals were famous: It's the cleanest engine room ever seen. The biggest Astaire-Rogers dance duet in the film is "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off," which is performed on roller skates in a park when Petrov and Linda try to evade pursuing reporters; it, too, seems designed more to get Astaire and Rogers on skates than to contribute to the plot. On the other hand, there's an obvious missed opportunity for a romantic duet to the Oscar-nominated song "They Can't Take That Away From Me," which Astaire sings to Rogers, but he doesn't follow through by dancing with her. He does dance to a few bars of the song when it's reprised later in the film, but his partner is Harriet Hoctor, a dancer whose specialty was a deep back-bend that she performed while en pointe. There's a sequence in which Hoctor does her thing while dancing backward toward the camera, which she is facing, that's flat-out creepy. Astaire-Rogers film regulars Edward Everett Horton and Eric Blore are on hand to do their usual fussbudget routines. Blore's bit in which he tries to tell Horton over the phone that he's been arrested and is at the Susquehanna Street Jail, constantly being interrupted in his attempts to spell "Susquehanna," is the film's funniest moment.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)