|

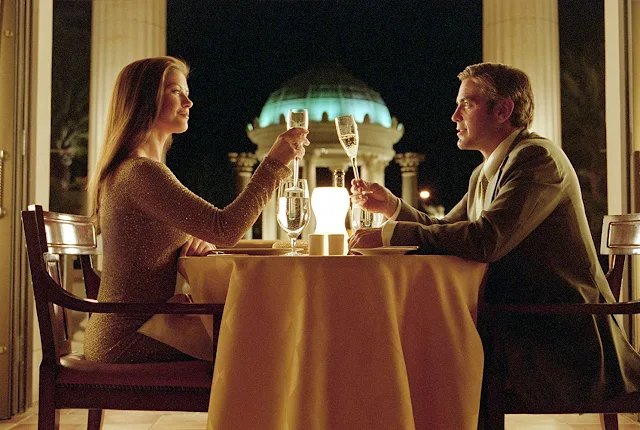

| Philip Seymour Hoffman and Ethan Hawke in Before the Devil Knows You're Dead |

This unrelentingly bleak family/crime drama was Sidney Lumet's last film as a director, and I can only say that he went out at the top of his form. That it was also one of the last films of Albert Finney and also starred another actor gone before his time, Philip Seymour Hoffman, only adds to its melancholy weight. Hoffman is at his best as Andy Hanson, the financially overextended older son, who tries to drag his brother Hank (Ethan Hawke) into a scheme to rob their parents' suburban mall jewelry store. Andy persuades Hank that it would be a victimless crime: They'd collect the loot and their parents would collect the insurance. Everything goes wrong with this scheme that you might imagine. It's complicated, for example, by the fact that Hank is sleeping with Andy's wife, Gina (Marisa Tomei). Hawke is superb in the role of Hank, a weak, spoiled younger brother now gone to seed -- a part that fits the actor perfectly as he ages out of the boyish good looks that once made some critics dismiss him as a lightweight. And midway through the film, when things have gone so wrong that the men's mother, Nanette (Rosemary Harris), lies comatose from the shooting that took place during the botched robbery, we meet Charles, their father, played by the always reliable Finney. The brothers are already in trouble because the wife and brother of the man Hank hired to do the job, who was killed in the heist, want hush money. Things get even worse when their father, urged implacably on by grief and anger, begins investigating what brought about his wife's death. Kelly Masterson's screenplay doesn't give Tomei enough to do in the story, but every moment when she's on screen is memorable, particularly the scene in which she leaves Andy. Lumet stages this in their apartment with a long take that holds Andy in the background as Gina struggles to haul her suitcase to the door, all the while delivering the news that she's been sleeping with his brother. Andy doesn't react immediately to this bit of information, but even later when he meets with Hank again, Hoffman lets us see how it's seething inside him. Before the Devil Knows You're Dead is not an easy film to watch; it's perhaps a little too grim and sordid for its own good. But at its best it's the kind of morality tale you might find in medieval literature, in the darker moments of Chaucer and Boccaccio, and it has some of the burden of greed and hubris that afflicts the families of Greek tragedy, even to the point of reversing the story of Oedipus in its stunning outcome.