A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Saturday, October 19, 2019

A Successful Calamity (John G. Adolfi, 1932)

A Successful Calamity (John G. Adolfi, 1932)

Cast: George Arliss, Mary Astor, Evalyn Knapp, Grant Mitchell, Hardie Albright, William Janney, David Torrance, Randolph Scott, Fortunio Bonanova. Screenplay: Maude T. Howell, Julien Josephson, Austin Parker, based on a play by Claire Kummer. Cinematography: James Van Trees. Art direction: Anton Grot. Film editing: Howard Bretherton. Music: Bernhard Kaun.

Hollywood's most memorable reactions to the Great Depression tended to be ironic: Ginger Rogers singing "We're in the Money" ("We never see a headline about breadlines today") in 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933) or nitwit socialites scavenger hunting in homeless camps for a "forgotten man" in My Man Godfrey (Gregory La Cava, 1936). But A Successful Calamity takes a different approach, almost an endorsement of Republican optimism about the economy, to the crisis. The movie opens with a scene in the office of the unnamed POTUS, who in 1932 would have been Herbert Hoover. (Although we don't see the president's face, the actor playing him, Oscar Apfel, wears Hoover's familiar high, stiff collar.) The president is welcoming financier Henry Wilton (George Arliss) back to the States after a year helping negotiate a deal about war debts. Wilton has yet to return to his home, where he expects to be warmly greeted by his wife, daughter, and son. Instead, he is met at the train station by his valet, Connors (Grant Mitchell), who explains that Mrs. Wilton (Mary Astor) is holding a "musicale" because she hadn't expected him until tomorrow, that his daughter, Peggy (Evalyn Knapp), is probably with her fiancé and couldn't have come to meet him because her car has been impounded after too many accidents and traffic tickets, and that his son, Eddie (William Janney), is playing in an important polo match. When Wilton discovers that his family is too busy socializing even to have dinner with him, he asks the valet if poor people have similar problems. No, Connors replies, poor people don't have enough money to "go" all the time. So Wilton gets the bright idea of telling his family that he's "ruined," whereupon they flock around him in support, vowing to get jobs or otherwise find ways to make ends meet. And when word leaks out that Wilton is on the skids, the news somehow enables him to make a killing on a stock purchase he's been angling for unsuccessfully. The moral seems to be that poor people really do have it better. It's an inane premise executed with modest finesse by a director known for his collaboration with Arliss on half a dozen other films, most notably Alexander Hamilton (1931), The Man Who Played God (1932), and Voltaire (1933). Arliss, one of the more unlikely stars of the early talkies, is an odd match for Astor, 38 years his junior. She plays Wilton's second wife -- the grown children are presumably from his first marriage -- but there's not much conviction or chemistry in their relationship.

Friday, October 18, 2019

Robinson Crusoe on Mars (Byron Haskin, 1964)

Robinson Crusoe on Mars (Byron Haskin, 1964)

Cast: Paul Mantell, Victor Lundin, Adam West. Screenplay: Ib Melchior, John C. Higgins, based on a story by Daniel Defoe. Cinematography: Winton C. Hoch. Art direction: Arthur Lonergan, Hal Pereira. Film editing: Terry O. Morse. Music: Van Cleave.

The average third-grader today can spot the scientific inaccuracies of Robinson Crusoe on Mars. Who doesn't cringe when Christopher Draper (Paul Mantell) tries to start a fire by feeding the flames with the oxygen from his supply tank, an attempt most likely to send him up in a large fireball? The special effects, too, are primitive: The attacking spaceships are two-dimensional, paintings on a black backdrop. But does any of this really matter? With older films, even science fiction, datedness often counts for less than style and substance. Byron Haskin's movie has both, largely because it's derived from a classic source, Daniel Defoe's 1719 tale of solitude and companionship. It plays on the primal fear of loneliness that makes solitary confinement the worst of punishments and is the backbone of many classic adventure stories, including such other great sci-fi films as 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) and The Martian (Ridley Scott, 2015). Even though Draper has a companion on Mars, a small monkey, his inability to converse with another human drives him near to madness -- a hallucination of his dead companion, Col. McReady (Adam West) -- before he finally encounters his Friday (Victor Lundin). Even then the breakthrough is slow to come: The alien humanoid at first refuses to speak, causing Draper to fume that he's "an idiot" and "retarded." But finally the alien trusts Draper enough to speak and the rapport blooms into a kind of interplanetary bromance as they learn each other's language and culture. (The master-servant Crusoe-Friday relationship remains, however: Draper expects his Friday to learn English first. Colonialism dies hard.) So forget everything we've learned from the various NASA probes about Martian terrain -- the absence of flaming volcanoes or of anything resembling "canals," let alone abundance of water and subaqueous plant life -- and accept the movie's vision for what it is: more a fable about long-ingrained human character than about what the future may be like. Byron Haskin's direction keeps the action crisp and steady, and while the studio sets have a certain cheesy quality, the footage shot at Death Valley's Zabriskie Point is often strikingly real.

Thursday, October 17, 2019

Reality Bites (Ben Stiller, 1994)

Reality Bites (Ben Stiller, 1994)

Cast: Winona Ryder, Ethan Hawke, Janeane Garofolo, Steve Zahn, Ben Stiller, Swoosie Kurtz, Joe Don Baker, John Mahoney, Harry O'Reilly, Susan Norfleet. Screenplay: Helen Childress. Cinematography: Emmanuel Lubezki. Production design: Sharon Seymour. Film editing: Lisa Zeno Churgin, John Spence.

Every generation seems to have a film that speaks to its disaffection with the older generation, which is accused of incomprehension of the needs of the young for self-fulfillment and identity. For my own generation it was Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955). For the Baby Boomers it was The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967). In Reality Bites, Ben Stiller seems to have set out to make the definitive film for Generation X, who find themselves underemployed after having expected, as Winona Ryder's Lelaina Pierce puts it, "to be somebody by the time I was 23." Instead, they're bitten by reality: held back by people like Lelaina's boss, a Houston morning-show host played with the grin and dead eyes of a shark by John Mahoney, or with their real lives neatly packaged (in "reality bites") for the MTV generation, as her documentary footage is by the producers of the company for which Ben Stiller's Michael Grates works. Some give up and go along, as Vickie (Janeane Garofolo) does when she accepts a job as manager of an outlet of The Gap, attending jeans-folding seminars. Others, like Ethan Hawke's Troy Dyer, accept their slackerhood: "I sit back and I smoke my Camel Straights and I ride my own melt." I think it's revealing that the meet-cute of Lelaina and Michael is brought about by a cigarette she throws into his convertible, causing their cars to collide. The amount of cigarette smoking in Reality Bites is an excessiveness we will probably not see again, but then this is a generation marked by AIDS and the threat of early death, so there's a kind of fatalism that pervades the lives of these characters. Reality Bites is not, I think, quite as distinguished a film as either Rebel Without a Cause or The Graduate. It spends too much time on the Troy-Lelaina-Michael triangle, with its predictable and rather sappy resolution, and not enough on Vickie and the closeted Sammy (Steve Zahn), whose stories -- her HIV test, his coming out -- are given perfunctory treatment. But there are enough bright lines and good performances to make it a movie worth revisiting.

Wednesday, October 16, 2019

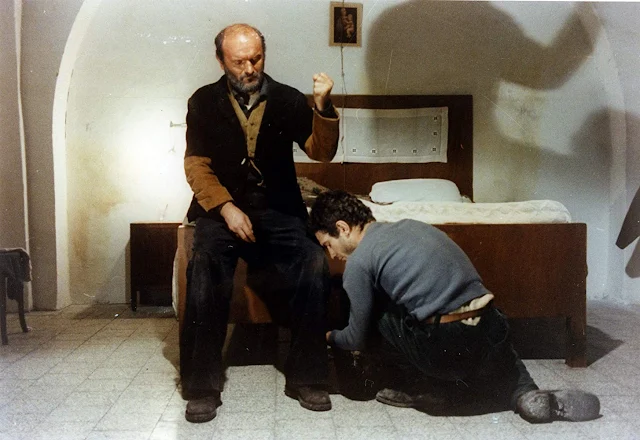

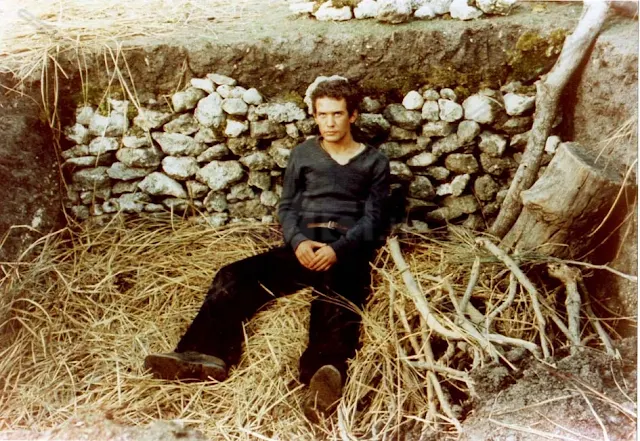

Padre Padrone (Paolo Taviani, Vittorio Taviani, 1977)

Padre Padrone (Paolo Taviani, Vittorio Taviani, 1977)

Cast: Omero Antonutti, Saverio Marconi, Marcella Michelangeli, Fabrizio Forte, Marino Cenna, Stanko Molnar, Nanni Moretti, Gavino Ledda. Screenplay: Paolo Taviani, Vittorio Taviani, based on a book by Gavino Ledda. Cinematography: Marino Masini. Production design: Gianni Sbarra. Film editing: Roberto Perpignani. Music: Egisto Macchi.

Two great themes coalesce in Padre Padrone. One is older than Oedipus, the primal conflict of father and son. The other came to the fore in the Enlightenment and the democratic revolutions it spawned; we now call it "social mobility." Poets used to write of flowers "born to blush unseen" and "mute inglorious Milton[s]," the victims of rural isolation, primitive ignorance, societies atrophied in feudal patriarchy. The Tavianis find both themes surviving in rural Sardinia, where Gavino Ledda's father drags him from school at the age of 6 and keeps him in servitude and illiteracy as a shepherd for the next 14 years. Padre Padrone could have been just a feel-good story about Gavino's triumph over his father's sternness and greed -- though the elder Ledda thinks what he's doing is for the son's own good -- but the Tavianis won't let it be just that. Though Gavino, rescued by compulsory military service from isolation and ignorance, becomes a celebrated linguist, an authority on the Sardinian dialect, the actual Gavino Ledda, appearing in a frame story for the dramatized part of the film, lets it be known that he has been permanently marked by his father. The Tavianis also find witty ways of letting the outside world irrupt into the young Gavino's isolation, as when the young shepherd hears an accordion playing and the soundtrack bursts into the overture from Die Fledermaus, a correlative for the world beyond the Sardinian hills. Later, after Gavino has begun to find his vocation but has been forced to return home, the aching beauty of the adagio from Mozart's Clarinet Concerto, to which Gavino is listening, is stifled when the father angrily drowns the radio in the sink. Gavino's feeling of being suppressed by his father finds a correlative when he joins a group of other young men carrying the effigy of a saint to a festival at the church. Hidden underneath the heavy statue, the men plot an escape to be guest-workers in Germany, but the camera pans up to the statue, which has changed to an image of Gavino's father, whose refusal to sign the necessary papers prevents Gavino from fleeing. Padre Padrone was made for Italian TV, and has been restored from 16mm film, so its images are sometimes a little muddy, but it gains real power from its storytelling and from the performances of Omero Antonutti as the father and Saverio Marconi as the grownup Gavino.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)