|

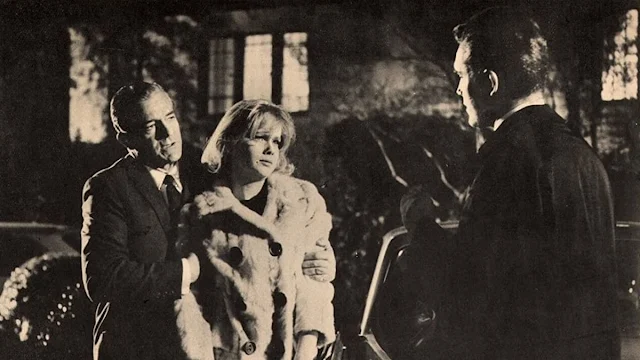

| Robert Ryan in Inferno |

Cast: Robert Ryan, Rhonda Fleming, William Lundigan, Larry Keating, Henry Hull, Carl Betz, Robert Burton. Screenplay: Francis M. Cockrell. Cinematography: Lucien Ballard. Art direction: Lewis H. Creber, Lyle R. Wheeler. Film editing: Robert L. Simpson. Music: Paul Sawtell.

Inferno is a smartly written, capably acted, and crisply directed thriller that deserves to be better known. The reason it isn't, I think, is that it was made during the early 1950s fad for 3-D movies, but happened to appear just at the end of that era, and it loses something when it's shown in 2-D. The story begins almost in medias res: The first characters we meet are the villains, Geraldine Carson (Rhonda Fleming) and Joseph Duncan (William Lundigan), who have just left her husband, the millionaire Donald Whitley Carson III (Robert Ryan), in the desert with a broken leg. Will he survive, and will the cheating lovers be caught? You probably can guess the answer, but there's a nice little ironic twist at the end. The movie's 3-D origins show in the usual way, with things getting thrust or flung at the camera, but they're usually integral to the action. Where it fails in the 2-D version is in its use of the Mojave Desert setting: Carson has been left at the top of a ridge, and to save himself he has to descend a steep and rocky hillside with a painfully fractured leg he manages to immobilize with a makeshift splint. There are shots of the slope from the top of the hillside, but they lose their vertiginous steepness when the movie is shown flat. The other obvious legacy of its 3-D origins is an "Intermission" title card that appears in mid-film. Inferno runs only 83 minutes, so it hardly needs an intermission for the audience's sake, but one was provided there for the projectionists. The 3-D movies of the '50s used two projectors running in sync, but most movie houses had only two projectors, which usually ran in alternation, with one showing the film and the other queued up with the next reel. When both projectors were running simultaneously, as they did for 3-D movies, theaters needed a time-out to swap out the reels. Still, unlike a lot of the era's 3-D movies, Inferno holds up well today.