A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Thursday, August 1, 2024

Brainstorm (William Conrad, 1965)

Wednesday, October 25, 2023

Fallen Angel (Otto Preminger, 1945)

|

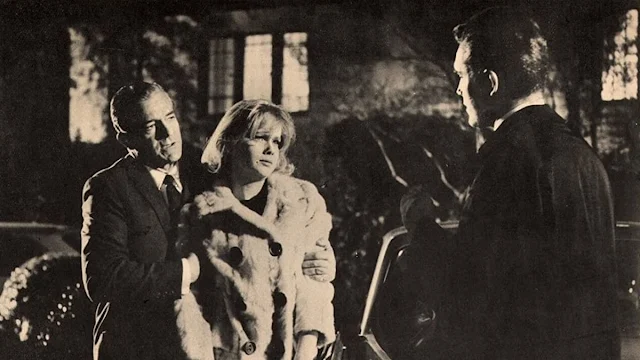

| Linda Darnell, Bruce Cabot, Dana Andrews, and Charles Bickford in Fallen Angel |

Cast: Dana Andrews, Alice Faye, Linda Darnell, Charles Bickford, Anne Revere, Bruce Cabot, John Carradine, Percy Kilbride. Screenplay: Harry Kleiner, based on a novel by Marty Holland. Cinematography: Joseph LaShelle. Art direction: Leland Fuller, Lyle R. Wheeler. Film editing: Harry Reynolds. Music: David Raksin.

Stuck with the inexpressive Alice Faye as his leading lady, Otto Preminger does wonders with the stranger-comes-to-town noir Fallen Angel. He plays it with only the slightest hint of a tongue in his cheek, taking its otherwise improbable turns of the plot with a straight face. It helps that he has a wicked counterpoint to Faye's blankness: Linda Darnell, as Stella, a waitress in a diner called -- what else? -- Pop's. It helps, too, that the stranger who comes to town is played by Dana Andrews with just enough charm and just enough sleaze to keep you guessing about what his character, Eric Stanton, will do next as the plot unfolds. Stanton arrives in a small coastal California town with not much more than a nickel for a cup of coffee at Pop's, and begins to plot how to con his way into some money. It just so happens that he hits town at the same time as another con man, Professor Madley (John Carradine), a spiritualist-seer. The Professor wants to put on one of his shows but has run into interference from the influential Clara Mills (Anne Revere), the spinster daughter of the late mayor of the town. Stanton wagers that he can win over Clara, which he does by wooing her pretty younger sister, June (Faye). (We have to take it on faith that he succeeds with June because Faye's expression is much the same after he wins her as it was before.) The upshot is that the Professor's show goes on, and Stanton makes enough from the deal to leave town. But he doesn't quite yet, because meanwhile he has hit it off for real with Stella. (Andrews and Darnell have genuine chemistry, which makes the lack of it in his scenes with Faye even more apparent.) And there's also the temptation presented by the fact that June has money and Stella doesn't, so he thinks up a scheme to got his hands on it and then leave town with Stella. No, it doesn't go as planned. In addition to Darnell and Andrews, there's a good performance from Charles Bickford as a retired cop who hangs out at Pop's and takes a key role in the plot when Stanton's scheme doesn't quite work out. Preminger gets fine support from cinematographer Joseph LaShelle, who had just won an Oscar for his work on Preminger's Laura (1944), which had also starred Andrews. Fallen Angel is no Laura, for sure, but it's better than it probably has any right to be.

Tuesday, November 10, 2020

Where the Sidewalk Ends (Otto Preminger, 1950)

|

| Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney in Where the Sidewalk Ends |

In Where the Sidewalk Ends, Dana Andrews plays Mark Dixon, a tough cop who's just a little too eager to rough up the suspects, and he starts the film by getting demoted for it That barely fazes him, however: When he's called on to interview Ken Paine (Craig Stevens), a suspect in a murder that's just been committed, Paine fights back and Dixon punches him out. Unfortunately, Paine had a severe head injury in the war, and he dies. Dixon's attempts to cover up only make things worse, leading to a snarl of consequences that form the plot of this darkly entertaining crime drama. What elevates Where the Sidewalk Ends into more than routine is mostly Ben Hecht's richly slangy, cynical dialogue and Otto Preminger's smooth direction. It helps, too, that Preminger is working with people who made his Laura (1944) one of the classics of Hollywood film: Andrews, of course, who even shares the name Mark with his cop counterpart in Laura, Gene Tierney as another leading lady with a lousy taste in men, and cinematographer Joseph LaShelle, who won an Oscar for the earlier movie. Laura was, however, almost baroque in contrast with the tight, spare Where the Sidewalk Ends, which depends on Hecht's skill at crafting tough talk to overcome some of the story's reliance on pop psychology: Dixon, it seems, developed his sadistic approach to police work because he hated his father, who was a hoodlum gunned down by the cops. The film ends on a nicely unresolved note after Dixon admits to killing Paine and trying to cover it up at the same time that he's being honored for bringing mobster Tommy Scalise (Gary Merrill) to justice.

Friday, May 17, 2019

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (Fritz Lang, 1956)

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (Fritz Lang, 1956)

Cast: Dana Andrews, Joan Fontaine, Sidney Blackmer, Barbara Nichols, Arthur Franz, Philip Bourneuf, Edward Binns, Shepperd Strudwick. Screenplay: Douglas Morrow. Cinematography: William E. Snyder. Art direction: Carroll Clark. Music: Herschel Burke Gilbert.

Tuesday, March 12, 2019

While the City Sleeps (Fritz Lang, 1956)

While the City Sleeps (Fritz Lang, 1956)

Cast: Dana Andrews, Rhonda Fleming, George Sanders, Howard Duff, Thomas Mitchell, Vincent Price, Sally Forrest, John Drew Barrymore, James Craig, Ida Lupino. Cinematography: Ernest Laszlo. Art direction: Carroll Clark. Film editing: Gene Fowler Jr. Music: Herschel Burke Gilbert.

Monday, January 29, 2018

The Best Years of Our Lives (William Wyler, 1946)

|

| Dana Andrews, Teresa Wright, Myrna Loy, Fredric March, Harold Russell, and Cathy O'Donnell in The Best Years of Our Lives |

Milly Stephenson: Myrna Loy

Peggy Stephenson: Teresa Wright

Fred Derry: Dana Andrews

Marie Derry: Virginia Mayo

Homer Parrish: Harold Russell

Wilma Cameron: Cathy O'Donnell

Butch Engle: Hoagy Carmichael

Hortense Derry: Gladys George

Pat Derry: Roman Bohnen

Mr. MiltonI: Ray Collins

Cliff: Steve Cochran

Director: William Wyler

Screenplay: Robert E. Sherwood

Based on a novel by MacKinlay Kantor

Cinematography: Gregg Toland

Film editing: Daniel Mandell

Music: Hugo Friedhofer

The Best Years of Our Lives is a very good movie, rich in characters and provocative incidents. It's not a great movie, but it's such a satisfying work of popular moviemaking that I'm surprised in this age of sequels and reboots, especially after the recent enthusiasm for the "Greatest Generation," no one has attempted a follow-up on the lives of its characters, taking them into the era of the Korean War, the nuclear buildup of the Soviet Union, the Cold War, McCarthyism, the civil rights struggle, and so on. Because there is something unfinished about the stories of Al, Fred, and Homer, not to mention Milly, Peggy, Marie, and Wilma, that perhaps director William Wyler and screenwriter Robert E. Sherwood couldn't possibly have foreseen in 1946. On the other hand, that's what makes The Best Years of Our Lives such a fascinating and useful document of its times. It's anything but an antiwar film -- although Homer Parrish has been mutilated, Fred Derry suffers PTSD nightmares, and Al Stephenson is well on his way to alcoholism, the film makes no effort to suggest that the war that inflicted these injuries on them was anything but just. The one naysayer, the "America Firster" who tangles with Homer and Fred in the drugstore, gets his just deserts, even if it costs Fred his job. What wins us over most is the performances: Fredric March overacts just a touch, but it won him the best actor Oscar. Harold Russell, the non-actor who received both a supporting actor Oscar and a special award, is engagingly real. And Dana Andrews proves once again that he was one of the best of the forgotten stars of the 1950s, carrying the film through from the beginning in which he seeks a ride home to the end in which he pays a nostalgic visit to the kind of plane from which he used to drop bombs. Neither Andrews nor Myrna Loy ever received an Oscar nomination, but their work in the film exhibits the kind of acting depth that makes showier award-winners look a little silly. Loy makes the most of her part as the wryly patient spouse, Teresa Wright manages to make a role somewhat handicapped by Production Code squeamishness about extramarital affairs convincing, and Virginia Mayo once again demonstrates her skill in "bad-girl" roles. Wyler was a director much celebrated by the industry, with a record-setting total of 12 nominations, including three wins: for this film, Mrs. Miniver (1942), and Ben-Hur (1959). He's not so much admired by those of us who cling to the idea that a director should provide a central consciousness in his films, being regarded as an impersonal technician. But Best Years is a deeply personal film for Wyler, who had just spent the war serving in the army air force, flying dangerous missions over Germany to make documentary films, during which he suffered serious hearing loss that threatened his postwar directing career. His experiences inform the film, especially the character of Fred Derry. In addition to the best picture Oscar and the ones for Wyler, March, and Russell, Best Years also won for Sherwood's screenplay, Daniel Mandell's film editing, and for Hugo Friedhofer's score. The last, I think, is questionable: Friedhofer seems determined to make sure we don't miss the emotional content of any scene, almost "mickey-mousing" the feelings of the characters with his music. It feels intrusive in some of the film's best moments, such as the beautifully staged reunion of Al and Milly, or the scene in which Homer, fearful that the hooks that replace his hands have destroyed his engagement to Wilma, invites her up to his room to help him get ready for bed, demonstrating the harness that holds his prostheses in place. It's a moment with an oddly erotic tension that doesn't need Friedhofer's strings to tell us what the characters are feeling.

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

Daisy Kenyon (Otto Preminger, 1947)

|

| Joan Crawford, Dana Andrews, and Henry Fonda in Daisy Kenyon |

Dan O'Mara: Dana Andrews

Peter Lapham: Henry Fonda

Lucille O'Mara: Ruth Warrick

Mary Angelus: Martha Stewart

Rosamund O'Mara: Peggy Ann Garner

Marie O'Mara: Connie Marshall

Coverly: Nicholas Joy

Lucille's Attorney: Art Baker

Director: Otto Preminger

Screenplay: David Hertz

Based on a novel by Elizabeth Janeway

Cinematography: Leon Shamroy

Art direction: George W. Davis, Lyle R. Wheeler

Film editing: Louis R. Loeffler

Music: David Raksin

Daisy Kenyon is an underrated romantic drama from an often underrated director. Otto Preminger gives us an unexpectedly sophisticated look -- given the Production Code's strictures about adultery -- at the relationship of an unmarried woman, Daisy, to two men, one of whom, Dan O'Mara, is married, the other a widowed veteran, Peter Lapham, who is suffering from PTSD -- not only from his wartime experience but also from the death of his wife. It's a "woman's picture" par excellence, but without the melodrama and directorial condescension that the label suggests: Each of the three principals is made into a credible, complex character, not only by the script and director but also by the performances of the stars. Crawford is on the cusp of her transformation into the hard-faced harridan of her later career: She had just won her Oscar for Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz, 1945), and was beginning to show her age, which was 42, a time when Hollywood glamour becomes hard to maintain. But her Daisy Kenyon has moments of softness and humor that restore some of the glamour even when the edges start to show. Andrews, never a star of the magnitude of either Crawford or Fonda, skillfully plays the charming lawyer O'Mara, trapped into a marriage to a woman who takes her marital frustrations out on their two daughters. Although he is something of a soulless egoist, he finds a conscience when he takes on an unpopular civil rights case involving a Japanese-American -- and loses. Set beside his two best-known performances, in Preminger's Laura (1944) and in William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), his work here demonstrates that he was an actor of considerable range and charisma. Fonda is today probably the most admired of the three stars, but he had always had a distant relationship with Hollywood: He suspended his career for three years to enlist in the Navy during World War II, and after making Daisy Kenyon to work out the remainder of his contract with 20th Century-Fox he made a handful of films before turning his attention to Broadway, where he stayed for eight years, until he was called on to re-create the title role in the film version of Mister Roberts (John Ford and Mervyn LeRoy, 1955). Of the three performances in Daisy Kenyon, Fonda's seems the least committed, but his instincts as an actor kept him on track.