Anecdote of the Jar

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.

It took dominion everywhere.

The jar was gray and bare.

It did not give of bird or bush,

Like nothing else in Tennessee.

--Wallace Stevens

How odd that my favorite 20th-century poet should have been a Taft Republican insurance company executive, of whom a colleague is supposed to have said, on reading his obituary in the New York Times, "I didn't know Wally wrote poems."

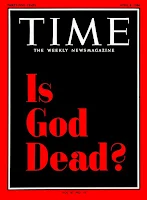

Stevens can be a tough nut to crack, unless you keep in mind one thing: his great theme is the transformative power of the imagination. It's what we have instead of religion ("Sunday Morning"); it's an intermediary between us and reality ("Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird"); it is God itself and "the ultimate good" ("Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour"). Everything else in Stevens' poetry is just window dressing.

But what window dressing, what wit, what imagery, what mastery of sound! Take the first line of this one: "I placed a jar in Tennessee." Why Tennessee? Why not Arkansas, or Washington, or Delaware, or any of several other three-syllable states? Of course, he needed a state with some wilderness in it, which maybe rules out Delaware, and Washington introduces that confusion between state and city, but when it comes to "slovenly wilderness," Arkansas would do as well as Tennessee. Except that then we'd have "jar" and "Arkansas," which sounds too easy.

And then there are those odd tricks of diction: the archaic inversion of "And round it was"; the phrase "of a port in air," which has commentators going in circles; and the mind-bending double negation "It did not give of bird or bush, / Like nothing else in Tennessee," with a further conundrum in the phrase "give of." Almost every one of the poem's 12 lines has something to taunt the explicators.

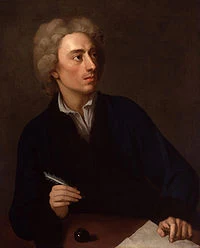

But really I think the poem is a response to Keats's "Ode on a Grecian Urn." It's not an ode, it's an anecdote (which lawyer Stevens probably knew wouldn't stand up as evidence in court). It's not a Greek vase, it's a Tennessee jar. It doesn't have a "brede / Of marble men and maidens overwrought, / With forest branches and the trodden weed"; it's "gray and bare" and doesn't portray any people, or even any birds or bushes. It's as plain and commonplace an artifact as you can find. And yet when he puts it in place, it makes Nature behave. Which is what art does -- even the simplest human creation like a jar sitting on a hill. The "slovenly wilderness" still sprawls, but the imagination has put it into perspective, has tamed it. And "fictive things" (jars, poems, Grecian urns) "Wink as they will."