A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Saturday, October 31, 2015

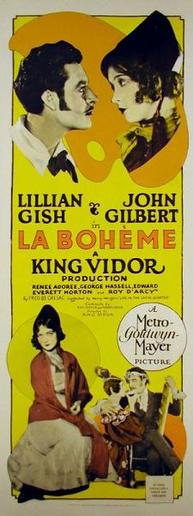

Still Alice (Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland, 2014)

After four previous nominations, Julianne Moore was overdue for an Oscar. I just wish she had won for a more challenging film than Still Alice, a middlebrow, middle-of-the-road movie that unfortunately suggests a slicked-up power-cast version of a Lifetime problem drama. It goes without saying that, with her luminous natural style, Moore can act the hell out of anything she's given: When she played Sarah Palin in Game Change (Jay Roach, 2012) on HBO, she even made me forget Tina Fey's great caricature of that eminently caricaturable politician, and did it without resorting to caricature. What bothers me most about Still Alice is its choice of an affluent white professional, a linguistics professor with a physician husband (Alec Baldwin) and an attractive family, to carry the burden of what the movie has to say about Alzheimer's. Why couldn't the film have been about the effect of early-onset Alzheimer's on a black or Latino family, or someone faced with meeting the bills -- a waitress or a secretary or a factory worker, perhaps? The screenplay (by directors Glatzer and Westmoreland, from Lisa Genova's novel) even shamefully asserts at one point that the disease is particularly difficult for "educated" people. The movie has its good points, of course. Kristen Stewart, as Alice's younger daughter, is a revelation. I haven't seen any of the Twilight movies, but I gather that even those who have were startled by the skill and maturity of Stewart's performance. And the scene in which Alice discovers the suicide instructions left by herself before the disease had progressed is deftly handled, as the disease itself prevents Alice from remembering and following through on the instructions. The film also has some poignancy in the fact that director-screenwriter Glatzer, who was Westmoreland's husband, suffered from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and died from the disease in 2015. But I think the use in Still Alice of excerpts from Tony Kushner's Angels in America, suggesting a parallel between Alzheimer's and AIDS, is unfortunate.

Friday, October 30, 2015

A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

|

| Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange |

Dim: Warren Clarke

Georgie: James Marcus

Pete: Michael Tarn

Mr. Alexander: Patrick Magee

Mrs. Alexander: Adrienne Corri

Deltoid: Aubrey Morris

Catlady: Miriam Karlin

Minister: Anthony Sharp

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick

Based on a novel by Anthony Burgess

Cinematography: John Alcott

Production design: John Barry

Costume design: Milena Canonero

Film editing: Bill Butler

Any movie that was panned by Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris, and Roger Ebert can't be all bad, can it? A Clockwork Orange remains one of Stanley Kubrick's most popular films, with an 8.4 rating on IMDb and a 90% fresh rating (93% audience score) on Rotten Tomatoes. I think it's a tribute to Kubrick that the movie can elicit such widely divergent responses. I can see what Kael, Sarris, and Ebert are complaining about while at the same time admitting that the film is undeniably entertaining in a "horrorshow" way: that being both novelist Anthony Burgess's Nadsat coinage from the Russian word "khorosho," meaning "good," and the English literal sense. For it is a kind of horror movie, with Alex as the monster spawned by modern society -- implacable, controlled only by the most drastic and abhorrent means, in this case a kind of behavioral conditioning. Watching it this time I was struck by how much the aversion therapy to which Alex is subjected reminds me of the attempts to convert gay people to heterosexuality. Which is not to say that Kubrick's film isn't exploitative in the extreme, relying on images of violence and sexuality that almost justify Kael's suggestion that Kubrick is a kind of failed pornographer. It is not the kind of movie that should go without what today are called "trigger warnings." What's good about A Clockwork Orange is certainly Malcolm McDowell's performance as Alex, one of the few really complex human beings in Kubrick's caricature-infested films. Some of his most memorable scenes in the movie were partly improvised, as when he sings "Singin' in the Rain" during his attack on the Alexanders, and when he opens his mouth like a bird when the minister of the interior is feeding him. Kubrick received three Oscar nominations, as producer, director, and screenwriter, and film editor Bill Butler was also nominated, but the movie won none, losing in all four categories to The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971). It deserved nominations not only for McDowell, but also for John Alcott's cinematography and John Barry's production design.

Thursday, October 29, 2015

The White Sister (Henry King, 1923)

Watching Lillian Gish in a film directed by Henry King after seeing her as directed by D.W. Griffith, Victor Sjöstrom, and King Vidor is, to say the least, instructive. All four of these movies are romantic melodramas (though The Scarlet Letter is lightly touched by the greatness of Nathaniel Hawthorne's novel), but Griffith, Sjöstrom, and Vidor each possessed a degree of genius, whereas King will never be regarded as anything more than a director of solid competence. Despite his long career, which ranged from 1915 to 1962, amassing credits on IMDb for directing 116 films, his movies are not particularly memorable. Who, today, seeks out The Song of Bernadette (1943) or Wilson (1944), two of the "prestige" films he directed for 20th Century-Fox? In his great auteurist survey The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929-1968, the best Andrew Sarris has to say about these and other movies directed by King is that they display a "plodding intensity." King was, in Sarris's words, "turgid and rhetorical in his narrative style," and that certainly holds true for The White Sister. Griffith, Sjöstrom, and Vidor all made use of Gish's rapport with the camera, her ability to suggest an entire range of emotions with her eyes alone -- hence the many close-ups she is given in their films. But King, filming on location in Italy and Algeria, is more interested in the settings than in the people inhabiting them. (Roy Overbaugh's cinematography is one of the film's virtues.) Nor does he seem interested in moving the story along, dragging it out to a wearisome 143 minutes. When Prince Chiaromonte (Charles Lane), the father of Angela (Gish) and her wicked half-sister, the Marchesa di Mola (Gail Kane), goes out fox-hunting, we're pretty sure that disaster is about to happen. But King stretches out the hunt so long that when Chiaromonte is killed the accident has no great emotional impact. And when Angela takes her vows as a nun, effectively preventing her from marrying Captain Severini (Ronald Colman), the man she loves but thinks is dead, King gives us every moment of the ceremony, trying to generate suspense by occasional cuts to Severini's ship steaming homeward. There's also an erupting volcano at the picture's end, but King fails to stage or cut it for real suspense. Gish is perfectly fine, though she's not called on to do much but look pious and to go cataleptic when Angela receives the news of Severini's supposed death. Colman is handsome but not much else, and Kane's villainy seems to be signaled by her talking out of the side of her mouth, as if channeling Dick Cheney many years in advance.

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

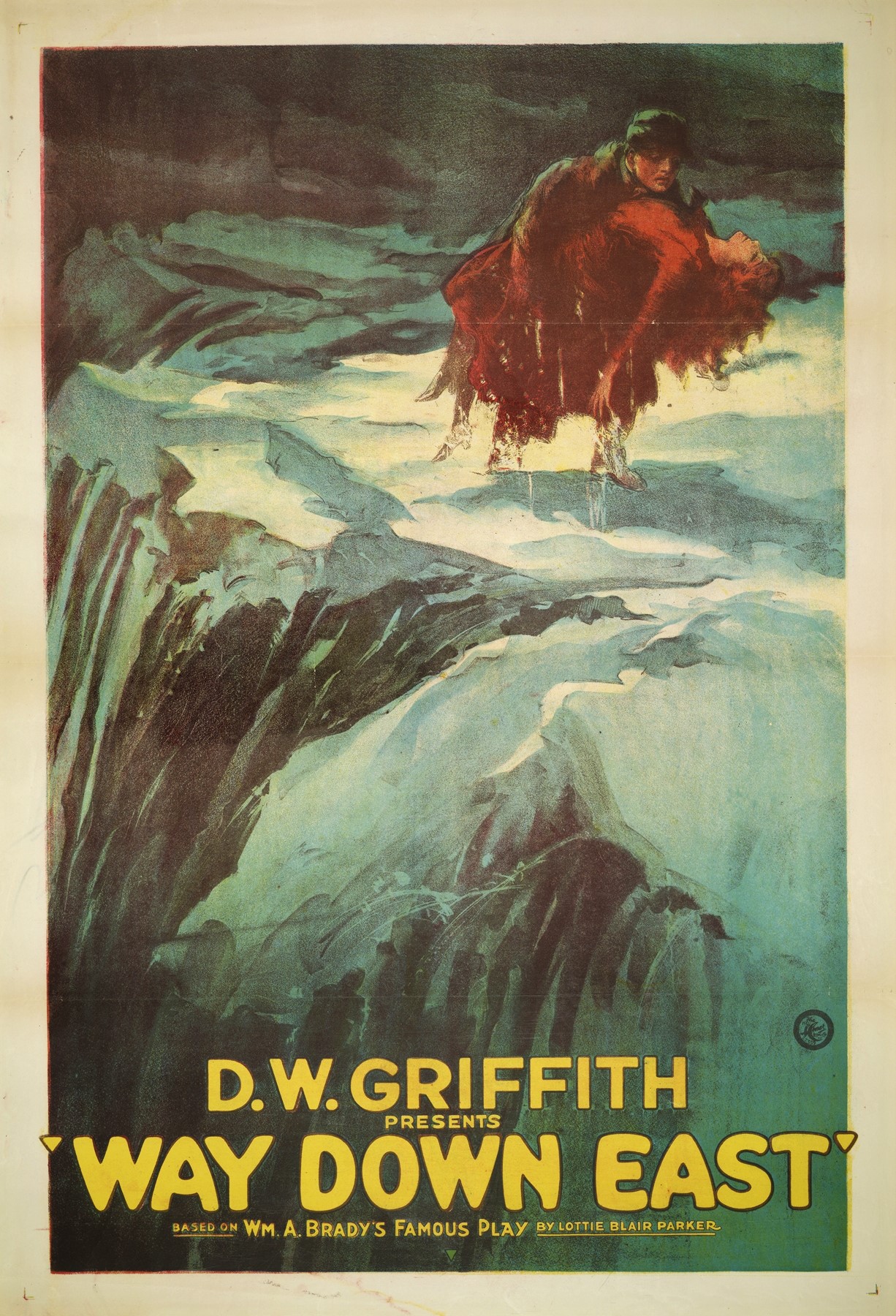

Way Down East (D.W. Griffith, 1920)

If Griffith's sententious title cards (e.g.,"Not by laws -- our Statutes are now overburdened by ignored laws -- but within the heart of man, the truth must bloom that his greatest happiness lies in his purity and constancy") don't have some viewers reaching for the remote, then the cornpone comic antics of his stereotypical rustics, such as the toothless constable (George Neville) and the hayseed Hi Holler (Edgar Nelson), certainly will. But stick with it to witness one of the great action sequences on film, Anna (Lillian Gish) adrift on the ice floe, as well as one of Gish's greatest moments as an actress, when she baptizes her dying baby. Yes, it's all hokum -- what do you expect from a melodrama almost a century old? But it's magnificent, enduring hokum, done brilliantly by a director who now seems more than just a pioneer but an artist of stature. And yes, that stature is tarnished by the man's racism in The Birth of a Nation (1915), just as Wagner's operas are tarnished by the anti-Semitism that many see lurking beneath their surface. But we don't have to endorse our artists to appreciate them, and the great efficiency with which Griffith tells a story and keeps us on the edge of our seats -- even when we know that his sentimentality is antique and outworn -- is something to be appreciated. Credit, too, must go to Billy Bitzer and the other cinematographers (Paul H. Allen, Charles Downs, and Hendrik Sartov) who gave us images that seem well beyond the years in which they were filmed. I do admit to some surprise that there are so many scenes in Way Down East that Griffith is content to film as if they were happening on a proscenium stage when one of his great contributions to the art of cinema is providing a fluidity and intimacy that are unavailable in the theater. Perhaps he was trying to do justice to his set designers, Clifford Pember and Charles O. Seessel, whose work is quite spectacular. But nothing before or since has quite equaled the ice floe sequence.

Tuesday, October 27, 2015

The Scarlet Letter (Victor Sjöström, 1926)

It's been many a year since I read The Scarlet Letter, but I'm pretty sure that any high school students who think they can get by watching Frances Marion's adaptation of it instead of reading Nathaniel Hawthorne's novel are likely to be disappointed in English class. That said, no film version is going to reproduce the depth of characterization, the symbolic force, or the intellectual density of Hawthorne, so we should be grateful for what this one does give us: one of Lillian Gish's greatest performances. This was Gish's second film for MGM, after La Bohème, and it suggests that her talents were better suited to a contemplative director like Victor Sjöström -- or Seastrom, as MGM insisted on anglicizing his name -- than to King Vidor's more action-oriented style. If her Mimi in La Bohème was disturbingly hyperactive, her Hester Prynne is a marvel of understated acting. She uses her eyes and mouth and the tilt of her chin to convey a miraculous range of emotions, from stubbornness to fear, from strength to frailty. It's a pity that her Dimmesdale, Lars Hanson, doesn't match her in subtlety. He's more successful in this regard in their 1928 collaboration The Wind, which was also directed by Sjöström.

Monday, October 26, 2015

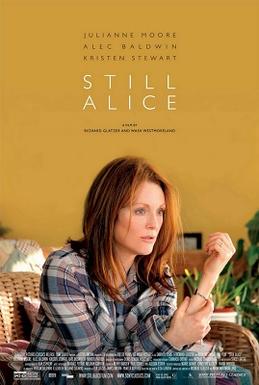

La Bohème (King Vidor, 1926)

Bohème without Puccini, except for a few themes from the opera interpolated into the piano accompaniment for the print shown on Turner Classic Movies. The screenplay by Fred De Gresac is said to be "suggested by Life in the Latin Quarter" by Henri Murger, which is also the source of the opera libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. But since the librettists took liberties with Murger, combining several characters and incidents from his fiction, it's pretty clear that De Gresac was a good deal closer to the opera version than to Murger. It's very much a vehicle for Lillian Gish, who wanted John Gilbert to play Rodolphe to her Mimi, but sometimes seems to be playing an anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-better game with her co-star. There is, for example, a scene in which Gilbert acts out the proposed ending to the play he is writing, with much swashbuckling. Then, a few scenes later, Gish acts it out again with similar verve for a potential backer for the play. Their courtship is a surprisingly hyperactive one, particularly in the scene in which they and their fellow bohemians go on a picnic that involves much running about. And Gish is not content to die calmly: On hearing that she won't live through the night, she makes a mad dash across Paris to be reunited with her lover, at one point allowing herself to be dragged along the streets while hanging onto the back of a horse-cart. Gilbert poses with feet apart and arms akimbo once too often, and the starving bohemians are given to much dashing and dancing. (Among them is the endearing and enduring Edward Everett Horton as Colline.) It's all a bit too much, and I have a feeling that the TCM print is being shown at the wrong speed, giving it that herky-jerky quality we used to attribute to silent films before experts corrected the speed at which they should be projected. The costumes are by the celebrated designer Erté, who is said to have had so much trouble working with Gish that he gave up designing for Hollywood.

Sunday, October 25, 2015

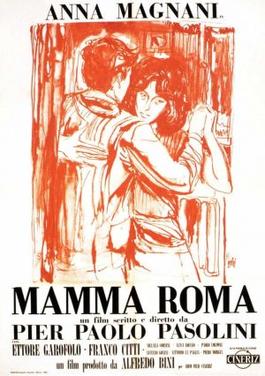

Mamma Roma (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1962)

Putting a force of nature like Anna Magnani in among the unknowns and non-professionals of the rest of the cast almost upends Pasolini's film, and it reportedly caused some friction between actress and director during the filming. If Pasolini really wanted the naturalistic Magnani of Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1948) it was much too late: By then, she had won an Oscar for The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955) and had become the flamboyant, histrionic Magnani who shows up on-screen in Mamma Roma. That said, Pasolini certainly gave her every opportunity to present herself that way, starting with the opening scene in which she herds pigs into the wedding dinner of her former pimp, Carmine (Franco Citti), and culminating in one of the greatest scenes (or rather, pair of scenes) of her career. I mean, of course, the long-take tracking shot in which she walks down a Roman street at night, delivering a monologue on her life, as people appear out of the darkness and recede back into it, serving as interlocutors. It's stunning the first time Pasolini (aided by his cinematographer, Tonino Delli Colli) does it, and even more remarkable when he reprises it after a crisis in her life. I think Mamma Roma is some kind of great film, notwithstanding Pasolini's tendency to be somewhat heavy-handed in his symbolism: witness the staging of the wedding dinner as a parallel to Leonardo's The Last Supper and of Ettore (Ettore Garofalo) strapped to a restraining bed to echo Mantegna's painting of the dead Christ.

|

| Top: Ettore Garofalo in Mamma Roma. Below: Andrea Mantegna, Lamentation Over the Dead Christ, c. 1475-78 |

Saturday, October 24, 2015

The Grim Reaper (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1962)

The Grim Reaper suffers from some inevitable comparisons. Because it's a film in which police investigating a crime are given accounts by people with varying points of view, it's often compared to Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950), even though Bertolucci claims he hadn't seen that film before making his. Because it's based on a story by Pier Paolo Pasolini, who also worked on the screenplay with Bertolucci and Sergio Citti, and producer Tonino Cervi said he wanted the film made in the style of a Pasolini movie, Bertolucci, who had worked on Pasolini's first hit, Accatone (1961), was judged and found wanting accordingly. And finally, the film doesn't measure up to Bertolucci's later work, such as The Conformist (1970) and Last Tango in Paris (1972). But considering that Bertolucci was barely into his 20s when he made The Grim Reaper, it's an impressive film, with a deft use of unknown actors and atmospheric Roman locations. The episodes in which the suspects are interrogated and we see the events they testify about in flashback are linked by a sudden thundershower in each episode and by sequences in which the victim, a prostitute, gets ready to go out to her fatal assignation. It's not compelling filmmaking, but a significant start to a major career.

Friday, October 23, 2015

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Mike Nichols, 1966)

I don't know if Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is a great play -- I've never seen it -- but it's not a great movie, perhaps because it sticks so closely to an uncinematic source. What it does have is one great performance, Richard Burton's, and one near-great one from Elizabeth Taylor. Unfortunately, George Segal and Sandy Dennis are miscast as Nick and Honey: He's too hip and she's too rabbity for their roles to take dramatic shape. Ideally, I think, Nick and Honey should be the conventional flies lured into George and Martha's sinister web. But as Mike Nichols directs them, they don't bring enough initial squareness to their parts, so their disintegration during the game-playing of their hosts happens too swiftly. What makes Burton's performance so memorable is his ability to shift moods, from sullen to mocking, from beleaguered to triumphant, in an instant. He also quite brilliantly suggests George's only barely latent homoerotic attraction to Nick, making it clear that he's titillated by the very idea of Martha's sleeping with the younger man. Taylor falters only in letting her Martha get too shrill for too long: A slower crescendo to her shrewishness would have been welcome in many scenes. Oscars went to Taylor and Dennis, but Burton lost to Paul Scofield in A Man for All Seasons (Fred Zinnemann, 1966) and Segal to Walter Matthau in The Fortune Cookie (Billy Wilder, 1966). Oscars also went to Haskell Wexler for black-and-white cinematography, Richard Sylbert and George James Hopkins for black-and-white art direction and set decoration, and Irene Sharaff for black-and-white costuming. This was the last year in which these categories were divided into color and black-and-white. It's sometimes observed that except for Cimarron (Wesley Ruggles, 1931), Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is the only film to have received nominations in every category for which it was eligible. But it's likely that if the color/black-and-white division had been eliminated a year earlier, the film would have been shut out of some of these categories. Though he was a noted cinematographer, Wexler doesn't do his best work on Virginia Woolf, partly because Nichols, making his directing debut, called on him to do some close-up shots that not only don't hold focus but also distract from the essence of the drama, the interplay of its four characters. Nominations also went to Ernest Lehman as the film's producer and screenwriter, Nichols as director, George Groves for sound, Sam O'Steen for film editing, and Alex North for score. Oh, and if you're wondering why the title is sung to "Here We Go 'Round the Mulberry Bush" instead of "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?", essentially killing the joke, it's because the Disney studios, who owned the rights to the tune, wanted too much money.

Thursday, October 22, 2015

Wild Tales (Damián Szifrón, 2014)

We don't see the "anthology film" of the type represented by Wild Tales much any more, except in movies like Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994) that take a group of somewhat interrelated stories and intercut them with one another. Damián Szifrón's movie is unabashedly a group of six short films that bear no essential relation to one another, except that they all deal with people at the breaking point and they all produce a macabre laughter. The movie was Argentina's entry in the best foreign language film category for the 2014 Oscars. (It lost to Pawel Pawlikowski's Ida.) Wild Tales takes off even before the credits with the mood-setting "Pasternak," in which a group of passengers on a plane all discover that, though they are strangers to one another, they are all in some unfortunate way acquainted with the plane's pilot who has ingeniously managed to get them on board together. (The pilot's murderous and suicidal intent is such an eerie foreshadowing of the May 2015 crash of Germanwings Flight 9525 that some theaters showing the film posted a warning.) My favorite of the episodes is "El más fuerte" ("The Strongest"), in which a road-rage incident snowballs to a deadly and hilarious conclusion reminiscent of a Warner Bros. cartoon in which Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck try to annihilate each other. My least favorite is probably the concluding one, "Hasta que la muerte nos separe" ("Until Death Us Do Part"), which depicts a wedding reception gone splendidly awry. It goes on too long, I think, but like all of the episodes it scores some satiric hits on its target, the wedding business. Other targets include the urban bureaucracy (everyone who has ever grumbled at the DMV will appreciate this one), the legal establishment, and the media's headlong rush to judgment.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)