|

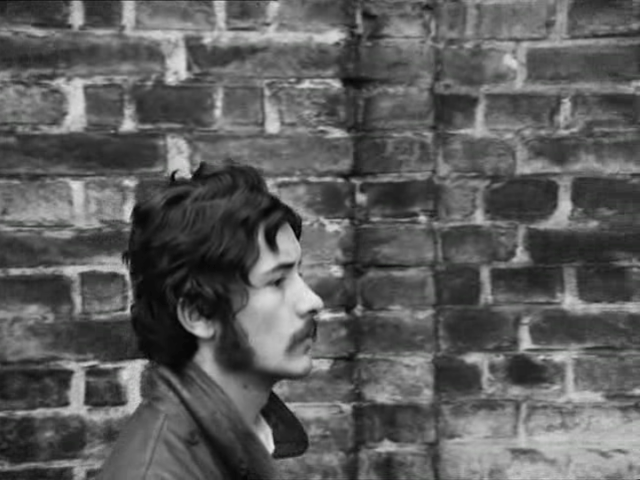

| Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Ulli Lommel in Love Is Colder Than Death |

Franz: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Johanna: Hanna Schygulla

Bruno: Ulli Lommel

Woman on Train: Katrin Schaake

Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Screenplay: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Cinematography: Dietrich Lohmann

Music: Holger Münzer, Peer Raben

I love Turner Classic Movies for its occasional programming surprises, but I have to wonder what its regular viewers thought if they stayed tuned to that channel after whatever Hollywood classic from MGM or Warner Bros. was over and started watching

Love Is Colder Than Death. For the audience for Rainer Werner Fassbinder's first feature film largely consists of (1) hard-core Fassbinder fans; (2) professional film scholars; and (3) compulsive film-bloggers. (Since I don't belong to either of the first two groups, I guess I have defined myself into the third.) The rest of the usual TCM viewers probably gave up on

Love Is Colder Than Death after a few minutes of the minimally staged, flatly lighted, tonelessly acted opening scenes, which look like a documentary of a performance in an experimental theater. (Like, for example, the Antiteater in Munich that Fassbinder helped found.) If they lasted through these scenes, which are about the attempt of the mob to recruit Franz and his first meeting with Bruno, they may have bailed out during an enigmatic conversation between Bruno and a woman he meets on a train, or shortly afterward, during Bruno's search for Johanna, the girlfriend Franz pimps out, a long sequence that consists largely of views of the nighttime streets down which Bruno is driving. Eventually, however,

Love Is Colder Than Death comes together into the story of the

ménage à trois formed by Bruno, Franz, and Johanna, and an ill-fated attempt to rob a bank. At this point it becomes clear that Fassbinder is mimicking and perhaps parodying the French New Wave. The

ménage is very much like the ones in Jean-Luc Godard's

Bande à Part (1964) and François Truffaut's

Jules and Jim (1962), though entirely lacking the

joie de vivre of either. In a somewhat shabbier way, Bruno emulates the gangster chic attempted by Jean-Paul Belmondo in

Breathless (Godard, 1960) and mastered by Alain Delon in

Le Samouraï (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1967). There's some of the larky post-adolescent lawlessness of

Breathless and

Masculin Féminin (Godard, 1966), as when the trio shoplifts sunglasses in a department store or Johanna and Bruno filch things in a supermarket, though Fassbinder's characters never seem to have much fun doing it. But there are touches throughout the film that might be called more Fassbinderish than Godardian. The supermarket scene is accompanied by several bars from a duet in Richard Strauss's

Der Rosenkavalier that have been looped endlessly into a kind of insane Muzak, giving an eerie, almost feverish note to the scene. For much of the film, Fassbinder avoids pans and zooms and other camera tricks, but when he uses them it's noticeable, as in the scene in which Franz is being held by the police for interrogation: The camera glides regularly back and forth along a steady track, without holding for a second on the person speaking -- it's like moving your head back and forth during a tennis match without focusing on the ball. It can't just be the absence of a budget for blanks and blood squibs that makes the several scenes in which people are shot so lacking in conventional movie realism: In each case, we hear the sound of the shot without seeing either smoke or a muzzle flash from a gun, and the victim falls down dead, like a kid in a playground pretend gunfight. And even the ending, which fades to white instead of black, seems like Fassbinder making fun of movie conventions. I don't know of many other movies that manage to be so derivative and yet so original at the same time.

Watched on Turner Classic Movies