|

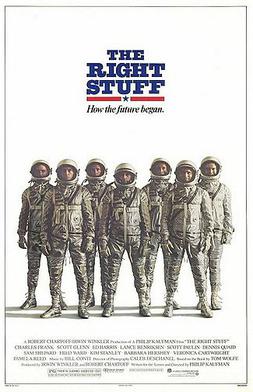

| Ron Silver and Barbara Hershey in The Entity |

Cast: Barbara Hershey, Ron Silver, David Labiosa, George Coe, Margaret Blye, Jacqueline Brookes, Richard Brestoff, Michael Alldredge, Raymond Singer, Allan Rich, Natasha Ryan, Melanie Gaffin, Alex Rocco. Screenplay: Frank De Felitta, based on his novel. Cinematography: Stephen H. Burum. Production design: Charles Rosen. Film editing: Frank J. Urioste. Music Charles Bernstein.

The Entity was inevitably compared to The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973), often unfavorably. Unlike the earlier film, The Entity doesn't dabble in theology to explain why Carla Moran (Barbara Hershey) is being subjected to terrifying attacks by an unseen assailant. Instead it dabbles in psychology and research into the paranormal. Neither of which ultimately can explain what's happening to Carla. The psychologist, Dr. Phil Sneiderman (Ron Silver), has a plausible diagnosis for what's happening to her, rooted in sexual repression. But not all of the pieces fit, and when Carla rejects the treatment Sneiderman proposes, the attacks continue. Carla, afraid of being judged mentally ill, turns to researchers in the paranormal, whose scientific bona fides is questioned by Sneiderman and his colleagues. When neither approach succeeds, Carla is left on her own. If the film works as anything more than a horror shocker it's because of Hershey's splendidly convincing performance, which takes the focus of the film off of the supernatural and onto issues of trust and credibility. Carla's plight becomes a parable about women who fail to find empathy and support for a personal trauma, particularly rape. But only that subtext saves The Entity from being anything other than a routine thriller.