|

| Joe Pesci and Barbara Hershey in The Public Eye |

Cast: Joe Pesci, Barbara Hershey, Stanley Tucci, Jerry Adler, Dominic Chianese, Richard Riehle, Richard Schiff, Jared Harris. Screenplay: Howard Franklin. Cinematography: Peter Suschitzky. Production design: Marcia Hinds. Film editing: Evan A. Lottman. Music: Mark Isham.

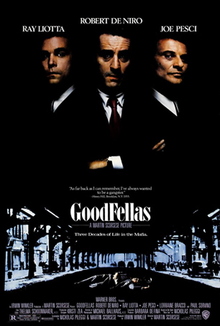

Before they were paparazzi, they were shutterbugs, and the most notorious of them was Arthur Fellig, known as Weegee. Fellig's ability to get to a crime scene first, often before the police, made him famous, but he also thought of himself as a serious documentary photographer. Howard Franklin based the protagonist of The Public Eye, Leon Bernstein, aka Bernzy (Joe Pesci), on Fellig/Weegee, including the character's willingness to cheat a little to make his pictures better. Bernzy, for example, coming upon a corpse before the cops arrive, rearranges the body a little to make the composition of the shot better. Once, he asks a bystander to toss the victim's hat into the frame: "People like to see the hat," he says. Weegee likewise knew how to pose and frame his pictures: One of his most famous documents the arrival of a pair of bejeweled and befurred dowagers at the Metropolitan Opera opening night in 1943, while a drab and frowzy woman gawps at them. It was published in Life magazine and in the following year was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, where the reaction to its comic juxtaposition gave the shutterbug a reputation as an artist. But it was not a candid photograph: Weegee and his friends had found a barfly, plied her with wine, and shoved her into the frame at just the right moment. Franklin gives Bernzy some of Weegee's duplicity, but he's more intent on making his shutterbug into a hero who uses his street smarts to foil a plot by the mob to muscle in on the distribution of gasoline rationing coupons -- the film takes place in 1942. He also falls in love with Kay Levitz (Barbara Hershey), a beautiful nightclub owner. In short, the movie is slick when it should be gritty. Pesci gives a restrained performance, almost as if he doesn't want to repeat himself, having just won an Oscar as the volatile Tommy DeVito ("What do you mean I'm funny?") in Goodfellas (Martin Scorsese, 1990). There are good performances by Hershey, Stanley Tucci as a young mobster, Jerry Adler as a newspaper columnist friend of Bernzy's, and Jared Harris as a doorman at Kay's nightclub. But the movie never builds the tension it needs for the story to have much payoff at the end.